Classical CD Review: Heras-Casado conducts Mendelssohn and Michael Tilson Thomas’s Berg

Michael Tilson Thomas proves he’s got Alban Berg’s style in his blood; Pablo Heras-Casado’s Mendelssohn symphony cycle continues to be stylish.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

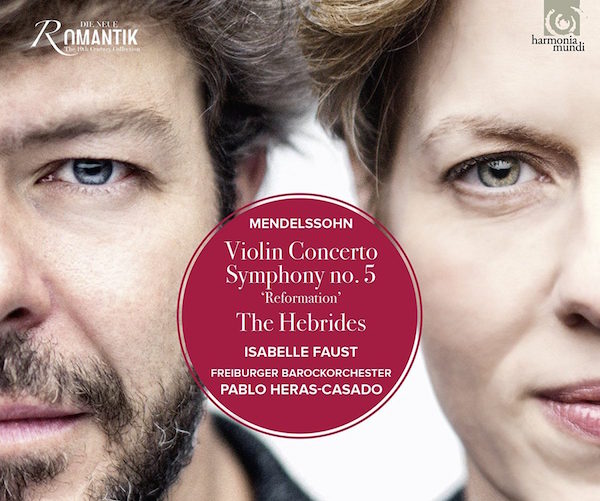

Violinist Isabelle Faust is about as non-complacent an artist as they come, so you don’t expect her to turn in a workaday interpretation of a warhorse. Her account of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, the opening selection on the third installment of Pablo Heras-Casado’s Mendelssohn symphony cycle for Harmonia mundi, doesn’t disappoint in this regard.

It’s strikingly unsentimental. Where so many fiddlers aim to imbue the first-movement cadenza with almost Shakespearean weight, for instance, Faust simply blazes through. The effect is breathtaking. In the quicksilver finger-work of the outer movements (especially the finale), Faust plays with blistering speed and precision, bringing to mind Heifetz’s great 1959 recording of the piece.

When she gets to lyrical bits, though, things change, and not necessarily for the better. In these spots – and there are many – she often resorts to swooping from pitch to pitch: up, down, sometimes side-to-side.

Granted, the idea behind this approach (which also includes minimal use of vibrato) is to emulate the playing of 19th-century virtuosi Ferdinand David and Joseph Joachim, and that at least provides it some historical justification. But that doesn’t keep it from becoming predictable or cliché. There is, perhaps, a good reason this style of playing went out of vogue.

Then there’s Faust’s tone, which, in part owing to her interpretive tack, is all over the map: sometimes timid, sometimes raw, and sometimes hearty. It adds up to an account of the solo line that is, by any definition, interesting, if not something that one imagines returning to regularly.

Odd as the fiddle playing can be, the orchestral accompaniment is wholly terrific: rhythmically taut and colorful. Heras-Casado draws playing of real vigor from the Freiburger Barokorchester even if, occasionally, certain instruments (like the timpani) are a bit too prominent.

Also stylish is the Reformation Symphony, which is in the same interpretive league as Heras-Casado’s 2014 recording of the Symphony no. 2. This isn’t Mendelssohn’s best symphony – the materials can come over a bit stodgily – nor his most exciting. But don’t tell that to Heras-Casado and the Freiburgers, who play it with furious energy. On the whole, their performance is a bit more urgent than Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s new account of the piece with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (no slouch, that one), though there are times (in the first movement, especially) when one might appreciate a bit more sonic heft. Still, the second movement is brilliantly fleet; the third, appropriately pensive and weighted; and the finale, thoroughly stirring. In all, this is a conspicuously fine period-instrument Mendelssohn Five.

Also strong is the disc’s filler: a fluent, periodically spacious reading of the Hebrides Overture. In it, Heras-Casado and the Freiburgers etch a salty, sea-sprayed portrait, one whose punchy attacks are balanced by creamy, songful interludes.

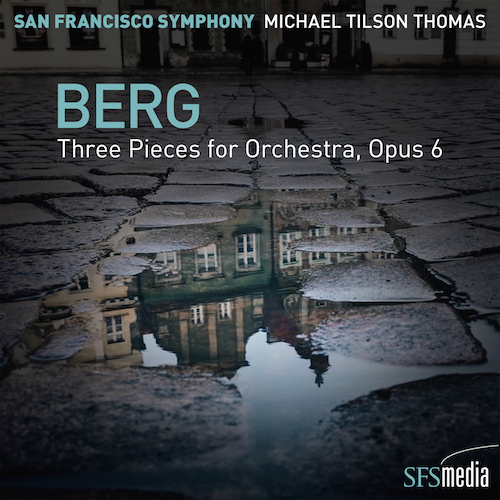

Michael Tilson Thomas might not be the first conductor you think of when it comes to the music of Alban Berg, but, as his new recording with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra (SFS) of that composer’s Three Pieces for Orchestra demonstrates, he’s more than got Berg’s style in his blood. Of course, given MTT’s affinity for all things Mahler, how could this not be the case?

Indeed, the new album – you can almost think of it as a three-movement, twenty-minute-long single – has much in common with the acclaimed SFS/MTT Mahler cycle of the last decade-plus. The sweeping gestures, pellucid scoring, impellent energy, and nebulous drama of the Mahler symphonies all left their marks on Berg’s 1914 score. And it can be a bit of a game to identify the reference points in Three Pieces (especially over the big, brooding final movement with its allusions to Mahler’s Fifth and Sixth Symphonies).

Here, the SFS revels in the intricacies of Berg’s scoring. The visionary last movement is played with intense clarity. The “Prelude” is suitably gauzy (and, at some points, notably the passages of high-trombone- and muted-brass writing, even anticipates the syncopations of jazz) while the “Round Dance” unfolds with dreamy nostalgia.

MTT sometimes takes, if not exactly a leisurely view, then at least a sumptuous approach. Accordingly, the first movement is, in his hands, a bit less harrowing than it is in Karajan’s classic account and the second more sentimental than Abbado’s. The finale moves with implacable momentum, highlighted by the SFS’s superb and bitingly fierce brass playing. In all, then, it’s a convincing performance, one that builds logically on the SFS’s strong Mahler tradition.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alban Berg, Harmonia Mundi, Isabelle Faust, Michael Tilson Thomas, Pablo Heras-Casado