Classical CD Reviews: Semyon Bychkov conducts Franz Schmidt and Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducts Mendelssohn Symphonies

The Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s new account of Franz Schmidt’s Symphony no. 2 with Semyon Bychkov is more than welcome; conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin does dazzlingly right by the symphonies of Mendelssohn.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Franz Schmidt is one of those composers who’s often dismissed with some variation on the epithet of “interesting symphonist.” Born in 1874, he was a contemporary of Schoenberg’s, though he never turned his back on tonality, which forever tarred him as a conservative in some camps. By the time he died in 1939, ambiguous, late-in-life support (never really reciprocated) from the Nazis ensured that his posthumous reputation was, for a time at least, sullied.

In between came a long teaching career and lots of music: operas, an oratorio, symphonies, concertos, chamber music, and a fairly substantial set of pieces for organ. If, in all of it, Schmidt was never quite the mold-breaker that Bartók or Stravinsky were over the same years, he was far more than a holdover from the late 19th century. Yes, his music is all firmly rooted in the Austro-Germanic tradition. But it tackles that history on its own terms. Along with contemporaries like Richard Strauss, Alexander Zemlinsky, and (from the next generation) Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Schmidt’s music suggests a non-dodecaphonic way forward that, if not for global upheaval, might have gained more durable traction in the concert hall.

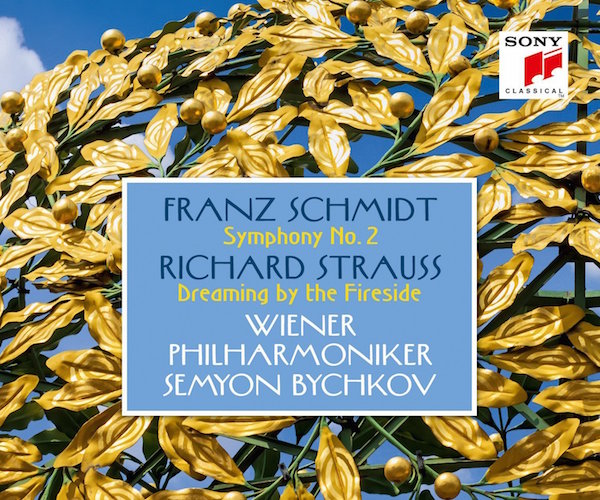

Schmidt’s four symphonies are each immensely difficult to pull together and, as a result, rare events to catch live. Recordings are few and far between, so the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s (VPO) new account of the Symphony no. 2 with Semyon Bychkov for Sony Classical is more than welcome.

Its main rival in the discography is Neeme Järvi’s classic account with the Chicago Symphony (CSO) on Chandos. Taped near the end of Sir Georg Solti’s long tenure with the ensemble, that’s a brawny and exuberant affair, featuring intense playing from the CSO capped by a stellar chorale from the Bud Herseth-led brass section.

In comparison, Bychkov’s performance sounds altogether more refined. The Viennese have Schimdt’s style – a cross between the rhetoric of Bruckner, the orchestral virtuosity of Strauss, and the harmonic progressions of Scriabin and Max Reger – in their collective blood (and vice versa: Schmidt was a member of the orchestra’s cello section early in his career). Accordingly, you hear everything in a different way in this reading. All the Symphony’s busy counterpoint is layered with exquisite transparency, both volume-wise and tonally.

These qualities go a long way to compensating for Bychkov’s tendency to take the long view of the music: unlike Järvi’s driving account, this one is unhurried and spacious, even when it might most benefit from some urgency. This is particularly true of parts of the outer movements.

The first one comes off best, though its clunky, start-stop structural argument takes a bit more time to settle than it otherwise might. In the finale, though, the music often seems to want to push forward while Bychkov holds it back. This is especially true of the big Brucknerian coda: here things almost grind to a halt, momentum-wise. Orchestral stamina isn’t in question – the VPO has more than enough gas in the tank to power through to the end, and they do. Rather, Bychkov seems to pushing at how gradually he can draw the music out yet keep it from toppling in on itself. It’s a curious experiment but a rather frustrating one at that.

Much better is his take on the long, inventive second movement. In it, everything clicks: the music (a mix of slow movement plus scherzo) sings and dances with quirky amiability and much fluency. The exchanges between winds and strings are often exquisitely done.

Filling out the album is Richard Strauss’s “Dreaming by the Fireside,” the second of four symphonic interludes from the opera Intermezzo. It’s an apt chaser, employing many of the same devices – not to mention a similar ear for luminous orchestral colors – as the Schmidt, and played with warmth and loving intensity by the VPO.

There have been any number of fine Mendelssohn symphony recordings out in the last few years: Pablo Heras-Casado’s “Lobgesang” and Andrew Manze’s “Scottish” Symphony stand out. But the crowning Mendelssohn of this decade (that I’ve heard, at least) belongs to Yannick Nézet-Séguin. The charismatic music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra and music director designate of the Metropolitan Opera has a stellar survey of all five symphonies with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe (COE) out now in a recording for Deutsche Grammophon.

The cycle is highlighted by a fantastic performance of the aforementioned “Lobgesang,” Mendelssohn’s much-maligned and -neglected Symphony no. 2. A hybrid symphony-cantata written to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Gutenberg’s invention of moveable type, it usually only turns up as part of complete Mendelssohn symphony surveys like this one.

Here, the excellence of the performance makes you question why. Everything comes to life. The “Sinfonia” proceeds with a lightness of touch and rhythmic tautness that ensures it all but floats on air. The singing of the RIAS Kammerchor is crisp and powerful in the outer choruses and richly devotional in the chorale on “Nun danket alle Gott.” And the soloists (sopranos Karina Gauvin and Regula Mühlemann, and tenor Daniel Behle) all acquit themselves excellently. The trio of sopranos and horn in “Ich harrete den Herrn” has hardly been bettered and “Stricke des Todes” comes off as a mini-operatic scene.

The “travel symphonies” are similarly exhilarating. In the “Scottish,” Nézet-Séguin doesn’t let anything dawdle. But he doesn’t rush through (or brush over) any of the music’s important details, like the first movement’s melancholy introduction or the stately, march-like episodes in the Adagio. The dancelike sections really kick and the Wagnerian climax to the first movement is played with gale-force fury.

Nézet-Séguin taps the lyrical vein of the “Italian” Symphony with a good deal of enthusiasm: the middle movements soar and, while the rhythmic exactitude on display in the outer ones never fails to impress, the melodic line is always given pride of place.

The First and Fifth have similar strengths. If, in the former, Nézet-Séguin doesn’t get the music to sound quite as zany and outlandish as Andrew Manze recently did, his is at least a thoroughly stylish and vigorous reading. Ditto the “Reformation” Symphony, the stodgiest of the set, which here is plenty lithe and pert.

Throughout, the COE plays with an attention to rhythmic detail and articulation that is particularly enlivening. This approach lends a freshness to Nézet-Séguin’s interpretations that is integral to their success. If you’re going to tackle these familiar pieces, you can’t hold anything back. Nézet-Séguin and his gang don’t. The results are a triumph on all fronts.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.