Film Reviews: Boston Jewish Film Festival –Two Looks at Jewish-American Comedy

Reviews of a trio of films at the Boston Jewish Film Festival.

The Last Laugh, directed by Ferne Pearlstein. Screening on Wednesday, November 16 at 6:30 p.m. and Thursday, November 17 at 1 p.m. at the Coolidge Corner Theatre; Saturday, November 19 at 9:15 p.m. at the Somerville Theatre.

Jerry Lewis: The Man Behind the Clown, directed by Gregory Monro, with The Man Who Shot Hollywood directed by Barry Avrich. Screening on Sunday, November 13 at 6:15 p.m. at the Jewish Community Center Greater Boston in Newton; Monday, November 14 at 10 p.m. at the Coolidge Corner Theatre.

Mel Brooks in a scene from “The Last Laugh.”

By Betsy Sherman

Two features in the Boston Jewish Film Festival deal with topics of Jewish-American comedy, and a short film paired with one of them introduces us to a man with special memories of Hollywood’s golden years.

The Oscar-winner Son of Saul was a fresh take on the Holocaust drama. The Last Laugh, by director/cinematographer Ferne Pearlstein, promises to be an unusual take on the Holocaust-related documentary. Pearlstein interviewed many of the major Jewish voices in American comedy about whether it is fair game to make jokes about the Holocaust (the film eventually broadens to include other major tragedies). There’s much worthy discussion, and a lot of well chosen clips, but the film is marred by being two films. And it isn’t merely that they’re not very well grafted together; the problem is that one part undermines the other.

The talking head portion has its subjects evaluate the overall appropriateness of using the Holocaust to get a laugh, and the factors taken into account by those who dare to craft such material. Among the interviewees are Gilbert Gottfried, Judy Gold, Rob Reiner, and Jeffrey Ross, and there are pertinent clips from stand-up performances, sitcoms and movies.

Naturally, the Jewish wit most associated with taking on Hitler is Mel Brooks. The movie includes the “Springtime for Hitler” number from the 1967 The Producers and related bits from History of the World, Part I. Yet Brooks, who considers his lampooning of Hitler and the Nazis as revenge by ridicule, has not and does not intend to base humor on what happened in the concentration camps. It’s heartwarming to hear him call Roberto Benigni’s vastly overpraised Life Is Beautiful “the worst movie ever made” because it avoided any reality of what went on in the camps.

When it comes to dropping the H-word, the boldest comedians have been Sarah Silverman and Larry David (he’s not interviewed, but clips from Curb Your Enthusiasm are included). Brooks reveals that although he laughed when Silverman told a deliberately cheesy joke involving the Holocaust at his AFI tribute, it made him uncomfortable. Silverman is interviewed for the film, and there are clips from her Sarah Silverman Program episode in which two characters try to outdo each other with their Holocaust memorials. What’s being made fun of there is the sanctimoniousness with which the Holocaust is presented (leading to offshoots such as jokes about Schindler’s List). Silverman is unapologetic about exploring this area, asserting that when her onstage persona says “Holocaust,” then “alleged Holocaust,” it’s to call out Holocaust deniers.

A sunny presence in the film is actor-singer Robert Clary, best known as LeBeau in Hogan’s Heroes. As the only member of his family that didn’t perish in the concentration camps, he credits his lifelong zeal for performing in helping him to survive. But most of the comedians come from postwar generations, and many of those are drawn to humor that explores the dark corners of human behavior. One forthright voice is that of writer-director Larry Charles, known for Seinfeld, Curb, and Borat. The documentary includes the simultaneously hilarious and chilling scene of Sacha Baron Cohen as Borat leading real-life honky-tonk patrons in a song that goes “let’s throw the Jew down the well.” Charles demurs that the things considered edgy in his work aren’t really taboo, since they’ve been allowed by the powers-that-be to see the light of day: once he gets thrown in jail, he’ll know he’s made something taboo.

The Last Laugh is also a portrait of Holocaust survivor Renée Firestone, whose sister Klara was killed at Auschwitz after having been the victim of medical experimentation. Firestone has a Dr. Mengele bit that comes from actual contact with Dr. Mengele—he told her, “If you survive this war, you’d better have your tonsils removed.” Oy. Firestone speaks on camera with Clary and more fellow survivors.

Maybe Pearlstein felt that viewers should have a realistic account of what the concentration camp experience was in order to judge its use as a subject for comedy. Firestone herself doesn’t joke about her experience, but she has a sense of humor and encourages friends to try to find joy even in their memories of that terrible time. What upends The Last Laugh is that the scenes with Firestone, which take up a good percentage of the screen time, follow the template of scores, if not hundreds, of Holocaust-survivor documentaries: the Museum of Tolerance visit, the reunion with other survivors, looking through a photo album, speaking to a class of young people. In this way, it becomes its own example of Holocaust-fatigue, the kind that forms a tempting target to skewer.

Jerry Lewis: The Man Behind the Clown does not, like The Last Laugh, mention the unreleased The Day the Clown Cried, the actor-director’s reportedly pathos-drenched period piece in which he plays a clown forced to lead children to the gas chamber (it’s discussed by Harry Shearer, who once saw a rough cut). But while it’s not able, in just an hour, to get to all of Lewis’s work, this French-Australian co-production directed by Gregory Monro is impressive in its depth and clarity, exploring what drives this very complicated man.

It’s a loving portrait, but not a fawning one. Monro covers the period from Lewis’s childhood, through the meteoric rise of the team of [Dean] Martin and Lewis, his solo work as an actor with director Frank Tashlin, his directorial work from 1960-65, his acclaimed performance in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy, and a glimpse of the MDA telethon (it’s too bad no one ever talks about the interesting, if flawed, movies Lewis directed after ’65).

A major asset is the inclusion of clips of Jerry from French TV. Some are super-serious discussions of the métier (Lewis published a book The Total Filmmaker), some are gag-filled concert excerpts, but the peach is a 1983 tribute hosted by Jerry chronicler Robert Benayoun that includes directors Louis Malle and Pierre Etaix (like Lewis, a Chaplin-inspired comic). Jerry manages to get his points about humor across to the French audience, and when the other panelists speak among themselves in a language he can’t understand, he wanders the stage, mugging at the audience. In addition, there’s fan Jean-Luc Godard on the Dick Cavett Show enthusing about Lewis’s use of space within the frame (“He’s more of a painter than a director”).

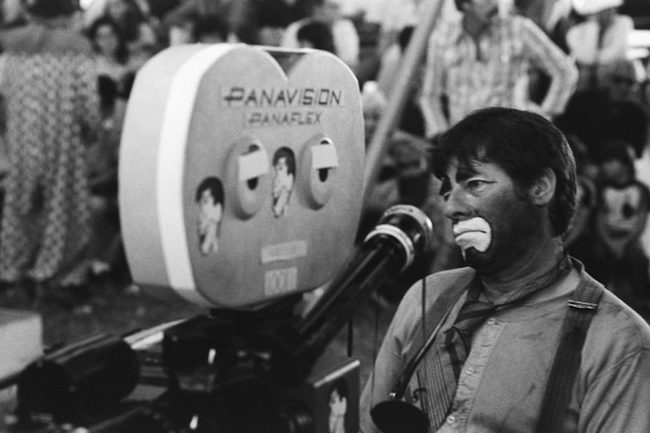

Jerry Lewis sitting next to a Panavision Camera. Photo; Owen Franken

The montages of clips from Jerry’s movies are superbly edited, working in tandem with music from the films and illustrating points made by the interviewees. Monro is particularly drawn to the films in which Jerry’s “The Kid” character brings chaos to the Hollywood studio system, The Errand Boy and The Patsy.

As per the title, there’s personality analysis of the man who started out as a lonely only child, his entertainer parents too busy even attend his bar mitzvah, for whom fame and riches came at a relatively young age. He worked out, as one author puts it, “the enigma of identity” with onscreen personas that seem to be one hundred percent from the id. His disruptive place in the pantheon of American male movie icons is noted (there’s no shortage of clips with Jerry in drag).

The elder Jerry (he’s now 90) is heard in voice-over, and only appears at the end of the movie. He’s a gentle old man commenting on photos from his past. For my taste, the movie doesn’t sufficiently acknowledge the part of anger and hostility in Jerry’s creative process (I’m a fanatical rooter-out of Jerry’s subtexts). As he strolls memory lane, Jerry is sparked by a photo of himself, during his directorial prime, looking through the lens of a movie camera. “This is the greatest love of my life, right there with her,” he says, pointing at the Panavision. “Great love affair. All my crew would go home after a day, and I’d take it home with me.” Sweet and creepy, just how I like it.

Barry Avrich’s The Man Who Shot Hollywood, playing with the Jerry Lewis film, uncovers the remarkable work of Yasha “Jack” Pashkovsky. A Russian Jewish immigrant who fell in love with silent movies, he went to Hollywood to be a cameraman but, unable to get in the union, toiled as a studio grunt. He did get to shoot the stars—with a still camera, off-set, as they entered and exited restaurants, or attended tennis matches. The results are wondrous. We see never-before-seen shots of, to name a few, Groucho Marx, Marlene Dietrich, Clark Gable and Gloria Swanson. Pashkovsky had kept his 400 negatives under his bed at the Motion Picture Country House, where Avrich met him. This film is a gem for star-hounds.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.