Visual Arts Review: Rediscovered Feminist Rebel — Artist Miriam Laufer

Clearly, the political and feminist works of the ’60s and ’70s make the case for Miriam Laufer’s place in the annals of post-war American modernism.

Views and Vignettes: The Work of Miriam Laufer at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Provincetown, MA, through Oct. 16

A glimpse of the PAAM show “Views and Vignettes: The Work of Miriam Laufer.” Photo: James Zimmerman.

By Timothy Francis Barry

It may be that rust never sleeps, but art world reputations can and do nod off: quite often artists and bodies of work that were once celebrated drift into the netherworld of the neglected or fall into the coma of the forgotten. For every Agnes Martin and Philip Guston — artists whose stature and influence continue to burgeon over the decades — there are slews of Janet Fishes, Vikky Alexanders, Jack Beals, and Rhonda Zwillingers — artists who once occupied museum spaces and took up pages of Artforum and Art In America, but whose reputations have now ebbed with the tides of art history.

Still, reputations are fluid. Sometimes seemingly evanescent figures are rediscovered, reintroduced by curators and scholars who have recognized something in their work that resonates with the cultural concerns of today. It is particularly noteworthy when a mid-20th-century artist — particularly one who never had all that much of an art-world profile in the past — is placed tentatively into the spotlight.

A half-century before New York had a Chelsea gallery district, there was an area called Tenth Street, noted for hosting early forays into what was then not particularly commercial art. Galleries such as Hansa and Tanager spawned the careers of George Segal and Claes Oldenburg, as well as other artists whose place in the canon is now assured. Back in 1962 the Phoenix Gallery, one of the Tenth Street group, presented the work of Miriam Laufer, a painter who may one day yet edge her way into the art history textbooks.

Miriam Laufer (1918-1980) was one of many art-world New Yorkers who summered in Provincetown after World War Two (hence the Ptown connection). The exhibition is sensitively curated by Johanna Drucker with the assistance of the artist’s daughter, Susan Bee (herself an artist who has collaborated with Drucker before). This expansive yet concise exhibition — 24 paintings and a handful of drawings — gives us Laufer trafficking in myriad aesthetic approaches that marry a lush and colorful painterliness to a serious, yet playful, version of leftist political agitprop. She samples from Pop, expresssionism, and figurative abstraction as needed.

Her depictions of the female body predate by several years the high-water mark of feminist art, yet many of the works in this show share the concerns of the recognized founders of that movement, including Judy Chicago, and especially Miriam Schapiro (who died in 2015) — some of whose works share a visual resemblance with Laufer’s.

Laufer’s expressions of strife and oppression are genuine; her father abandoned the family when she was eight, after which she and her brother were placed in an orphanage. In 1934 they were evacuated from Germany to Israel, just ahead of incipient Nazi brutality. She won a scholarship to art school, studying to become a graphic designer. She later lettered signs for the British army in Palestine, before emigrating to New York in 1947, where she found a career as a commercial artist and illustrator.

A 4-foot high by 3-foot wide painting from 1968, Black and White, loudly announces Laufer’s politics: it features an image of a tall and strapping nude woman, one hand defiantly on her hip, the other hand brandishing a pistol. It is part of the painting-as-journalism movement — it smacks of the Red Brigade, Eldridge Cleaver and the Black Panthers, yellow flames from burning bras, dripping green slime perhaps from wading through Mekong Delta rice-paddies….

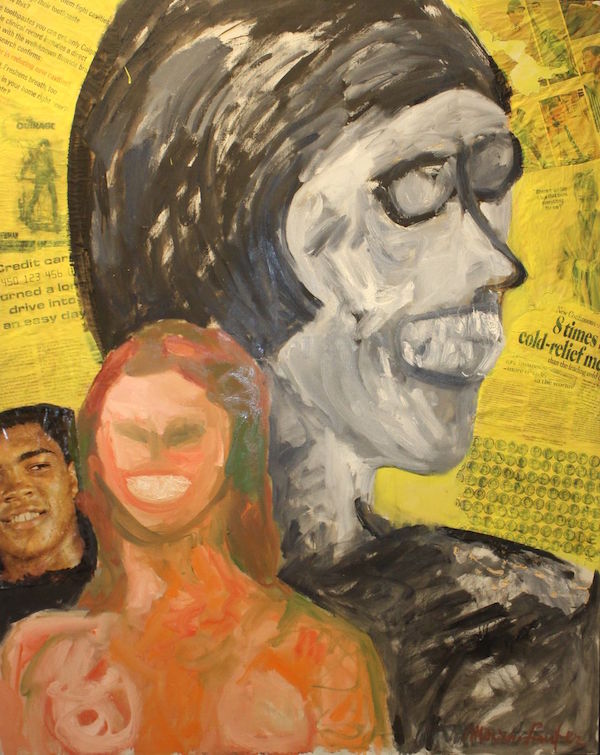

“Untitled (two women with Mohammed Ali),” Miriam Laufer. Photo: Courtesy of PAAM.

Another large oil on canvas with collage, Untitled (two women with Mohammed Ali) c. 1965, shows that Laufer was squarely in the mainstream of avant-garde art’s currents; the collaged elements of Ali’s face and found snippets of newspaper headlines are inspired by the vocabulary found in Rauschenberg and Johns of this period, while the stencilled-letters in a 1968 self-portrait and other works in the show place her in the good company of Larry Rivers (though keep in mind that lettering was part of Laufer’s early years as a graphic artist).

Laufer took a brave path. As critic Robert Atkins has put it, “Until the end of the 1960s most women artists sought to ‘de-gender’ art in order to compete in the male-dominated, mainstream art world.” It seems that her relative obscurity gave her the license to do just what she wanted.

Her figure-drawing seems inspired by Matisse, her vivid palette owes a debt to the Fauves, and her muscular brushwork implies a nod to Chaim Soutine: despite these strong influences, the resulting amalgamations often attain considerable originality. One wall of 1950s and early ’60s abstractions and portraits come off as well-executed period-pieces, as beautiful to look at as they are inconsequential when seen in the light of Laufer’s later, mature works.

Clearly, it is the political and feminist works of the ’60s and ’70s that make the case for Laufer’s place in the annals of post-war American modernism. Whether her work is afforded a place alongside other feminist provocateurs, such as Hannah Wilke, Miriam Schapiro, and (the also recently “rediscovered”) Rosalyn Drexler, won’t be settled for some time yet. One thing in her favor: the “vignette” nature of these paintings won’t challenge the limited attention-span of today’s Instagram crowd. That, coupled with their ever-relevant subject matter, should serve them well in the fight for Laufer’s survival in the art world sweepstakes.

Tim Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

Tagged: Johanna Drucker, Miriam Laufer, Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Susan Bee, Timothy Frances Barry