Arts Commentary: Lenny Bruce — On the 50th Anniversary of his Death

What made the authorities especially eager to tape Lenny Bruce’s mouth shut was his vigorous social and religious satire.

Lewis Black on Lenny Bruce: “There hasn’t been a comic who has worked since Lenny who doesn’t owe him a debt of gratitude.”

By Betsy Sherman

On August 3, 1966—the summer’s day on which comedian Lenny Bruce died of a drug overdose at age 40 in his Los Angeles home—I was probably preoccupied with day camp. On this year’s fiftieth anniversary of that event, I feel its importance down to my marrow. This has been my year of immersion in all things Lenny Bruce.

During the winter, I was hired to listen to, describe and catalog the audio portion of Brandeis University archives’ Lenny Bruce Collection. This trove of tapes (now digitized), photos, writings, memorabilia, and other ephemera was acquired by Brandeis (made possible by a grant from the Hugh M. Hefner Foundation) from Kitty Bruce, daughter of Lenny and Honey Bruce, in 2014. Months after the job wrapped up, my research into Bruce’s life and work continues, and will at least until Brandeis’ upcoming conference “Comedy and the Constitution: The Legacy of Lenny Bruce” (October 27-28, 2016 at Goldfarb Library). At the event, the Lenny Bruce Collection will be formally opened for use by scholars who visit the archives.

The poster boy for what was called “sick comedy” in the late 1950s and early ‘60s was stigmatized, and prosecuted, for performing material about sex that’s tamer than what we can now see on a typical episode of Broad City. But what made the authorities especially eager to tape his mouth shut was Bruce’s vigorous social and religious satire.

Born Leonard Alfred Schneider on October 13, 1925, on Long Island, Bruce was an only child whose parents divorced when he was young. His mother, a burlesque dancer and comic who adopted the name Sally Marr, encouraged his sense of humor, so it’s not surprising that after his stint in the Navy in World War II, Lenny took to the stage. The idiom of the day was Borscht Belt set-up/punchline humor, and Bruce achieved some distinction doing comic impressions. In 1951, he married a stripper known as Hot Honey Harlow, who would become his muse. Later in the decade the couple moved to Los Angeles and Lenny emceed at strip clubs. It was a trial by fire, and he succeeded in entertaining crowds who’d only come to ogle female flesh. But it was in the Beat territory of San Francisco where he developed a more confessional approach on-stage, and was appreciated as an iconoclast with a personal point of view. His peers in this comedy vanguard included Mort Sahl, Shelley Berman, and Jonathan Winters. Bruce’s career ascent, as well as its descent, was fueled by drugs; he was most fond of amphetamines, but also indulged in narcotics.

The unpredictability that made Bruce an exciting performer—he “cooked” like a jazz musician—made the forces of the establishment, in show business and beyond, nervous. As the 1960s progressed, Bruce racked up arrests for onstage obscenity and drug possession. Consequently, he added to his repertoire of bits a lively reportage of his clashes with the justice system. This portion of his set grew until, in the minds of some alienated fans, the lectures on the law pushed out the comedy altogether (his later work is fascinating in retrospect, but I can understand how it may have been puzzling, to say the least, for audience members at the time). By 1963, few venues would book him, and a 1964 conviction for obscenity in New York was the nail in the coffin (Bruce was given a posthumous pardon by Governor George Pataki in 2003). The comedian had himself declared a pauper not long before his death.

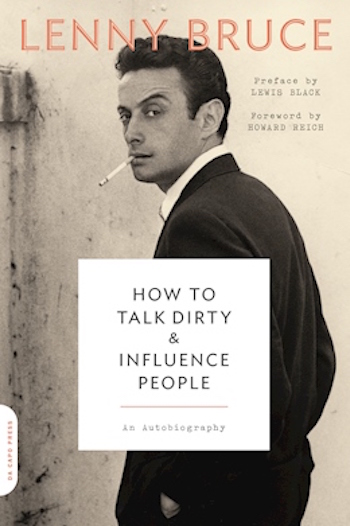

Bruce’s work and reputation were elevated to cult stature during the 1970s. His reputation has alternately swelled and ebbed in the years since. Among today’s comedians who embrace his legacy are Richard Lewis, Marc Maron, Louis CK, Sarah Silverman, Margaret Cho, Gilbert Gottfried and Lewis Black. Black wrote a preface for the newly re-released edition of Bruce’s 1965 autobiography How to Talk Dirty and Influence People (available from Da Capo Press), saying, “There hasn’t been a comic who has worked since Lenny who doesn’t owe him a debt of gratitude.”

I count myself a Lenny fan from way back. I was given (not by my parents) a red vinyl copy of the 1961 LP Lenny Bruce – American when I was about 15. My favorite track was “Lima, Ohio,” which hilariously dealt with two divides: the one between performers and civilians, and the one between Jews and gentiles in white-bread middle-America. A close second was the prison-movie parody “Father Flotsky’s Triumph,” in which Bruce offered a litany of 1930s character actors whom I would soon come to cherish.

By the time I got hooked, Lenny was gone, but his 1970s canonization had begun and his chroniclers were busily casting surrogates for him. I saw the play Lenny, with Marty Brill in the title role at Boston’s Charles Playhouse, and of course the Bob Fosse movie version starring Dustin Hoffman and Valerie Perrine.

But there wasn’t much of Lenny himself to be seen on film or video, and there haven’t been miraculous discoveries of footage during this age of youtube. Documentaries, such as the brilliant 1998 Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth (originally on HBO, and never released on DVD), contain clips from his appearances on The Steve Allen Show and Playboy After Dark. Network TV didn’t want to touch him. His larger concerts weren’t filmed, and the only full club set captured is of one of his last shows. Called The Lenny Bruce Performance Film, it’s crudely made, and features the transcript-reading that’s anathema to many, but I find it funny as well as engrossing.

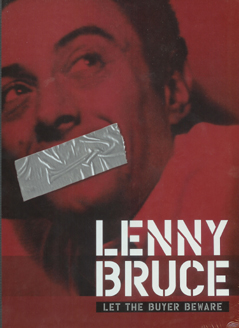

So it’s in the realm of audio that discoveries are being made. In 2004, Shout Factory! released the six-disc boxed set Let the Buyer Beware, which had clips from some of Lenny’s personal tapes as well as his performances. The audio in Brandeis’ Bruce Collection expands upon that material, with 21 full or partial nightclub sets and fuller versions of many of the personal tapes excerpted for the boxed set.

Whereas the commercially released albums from Lenny’s heyday were edited-together highlights of various gigs, the raw sets in the Bruce Collection are a real you-are-there experience. We can hear the clink of ice in glasses, the murmur of the audience, snatches of jazz before the intro and after the set’s end, Lenny’s quips to or about the various club owners, and tense exchanges with offended patrons who are walking out. Flaws, now exposed—such as a frequent inability to segue—become endearing. The listener can feel Bruce, in the moment, on the balls of his feet like a tennis player, volleying hipster lingo and Yiddish (which he made hip), to patrons who probably resemble extras from the early seasons of Mad Men. It’s exhilarating.

In my work with the tapes, I got to dive into and explore discrete phases of Bruce’s work. By chance, I started with some performances from his contentious engagement at the Gate of Horn club in Chicago during November and December of 1962. Lenny was arrested three weeks into the gig, in the early hours of December 5 (excerpts from a transcript of “The Bust Show” appeared in the June 1963 issue of The Realist, which can be read online). The charge was obscenity, but it was apparent from remarks made by the police that the bust came not so much because of the act’s sexual content or its curse words as because Bruce mocked the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

An earlier Bruce bit called “Religions Inc.” depicted all clergy (including those of Bruce’s tribe, the Jews) as snake-oil salesmen turned business tycoons. His “Christ and Moses” had the eponymous figures come back to earth, their example of purity discombobulating institutional leaders such as Cardinal Spellman. By ’62, Bruce was startling audiences by saying the only true Christian was Jimmy Hoffa, because he hired ex-convicts—as Christ would have.

Real life had the last rueful laugh. Bruce’s Chicago trial, which took place in February 1963 and ended in conviction (later overturned), would come to be known as the Ash Wednesday Trial. On that religious holiday, the judge, the two prosecutors and all 12 jurors arrived in court with crosses of ash on their foreheads.

The Bruce Collection contains a string of performances at the Gate subsequent to the arrest, and it’s downright thrilling to hear Lenny still in there, not pulling punches, not censoring himself. He riffs about the arrest, and about his previous trial for obscenity in San Francisco, as well as performing favorites such as his Lone Ranger deconstruction, “Thank You Masked Man.” With gusto, he goes on the warpath against Chicago columnist Paul Molloy, a conservative Catholic. Bruce is angry, but he exudes a real desire to connect with his audience.

For the next bloc of shows I listened to, it was like getting in a time machine. These sets, from the spring of 1959, had a completely different feel. Bruce’s star is on the rise, and he’s playing a tiny Manhattan club called The Den at the Duane Hotel. The hometown boy has made good, and the sophisticated crowd is on his side. There’s a crackle of excitement in the air. It’s before the obscenity arrests, so Bruce isn’t yet on a mission. Although some of the material is weighty, decrying segregation and capital punishment, there’s a lightness about him. He can even be silly. He ribs some young cadets in the audience and—the visuals have to be imagined—does a bit with a sword belonging to one of them. He dons a cadet’s (presumably white) jacket, immediately becoming a disgruntled ice cream man: “Fuck Good Humor!”

By contrast, the next period, while an extremely rewarding learning experience, was impossible to listen to without some degree of heartache. During the summer of 1964, Bruce’s burden is heavy. He does these shows at San Francisco’s Off-Broadway club before and after his New York obscenity trial wraps up (he also has a bout with pleurisy that season). Lenny has become a cause-célèbre for some, but a pariah to most. His material is densely packed with references to controversies of the time, presented through his very distinctive prism. He imagines the origin of obscenity law, and gets specific about how the charge has been laid on him. But there are belly laughs amidst the pedantry. Never really a political satirist, Bruce gives a gut-feeling read of the Barry Goldwater phenomenon. He ponders the Republican nominee’s family’s Semitic roots and predicts that, once he’s elected president, Goldwater will rip off a mask and reveal himself to be a Jewish pornographer.

Certain qualities are consistent throughout these phases of the comic’s career. Bruce was endlessly curious, and was the farthest thing from a snob when it came to acquiring knowledge. He delightedly shares with a Chicago audience a new phrase he learned from a vice cop: that a gay black flasher (okay, he says “Negro faggot flasher”) used the priceless come-on line, “Hey baby, how’d you like to look at this roll o’ tar paper?!” So refreshing, Lenny contends, compared to the usual tired double-entendres. Bruce was disgusted by people’s willingness to cast the first stone, and encouraged listeners to look within to see whether they had the right to judge. A routine about Francis Gary Powers—you know, that shot-down pilot from Bridge of Spies—was called “Would You Sell Out Your Country?” Bruce posits that if he, Bruce, witnessed a fellow prisoner-of-war getting a “hot lead enema” from their captors, he’d not only spill military secrets, he’d start making secrets up.

Lenny Bruce — he led “an embattled, barbed-wire existence.”

In this vein, Bruce practiced a sort of audacious empathy. He’d put himself in the shoes of even those you’d think he’d consider enemies, like cops, whom he’d usually refer to as “peace officers” (not necessarily ironically). He’d paint them as working stiffs, and urge audience members to “hab rachmonas for the heat” (have sympathy, in Yiddish). The limits of this empathy? Interestingly, it was a case of turning on his figurative family—he excoriated the older generation of entertainers, mostly the Jewish ones, as rich, bloated hypocrites. Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor got theirs, but Bruce was particularly venomous towards singer-comic Sophie Tucker (now his archival sister, since her scrapbooks reside at Brandeis).

One of the treasures of the tape collection is a one hour and twenty-one minute conversation that could be condensed into a wicked one-act play. The date: January 25, 1966. The place: Lenny Bruce’s Los Angeles house. The participants: Bruce, Allen Ginsberg and Phil Spector. Spector had swooped into Lenny’s life as a would-be rescuer, lending financial support and backing a comeback engagement at an L.A. venue called The Music Box. It’s less than two weeks before the show, which will end up a critical and commercial failure. To his tête-à-tête with Bruce, Spector has brought Ginsberg, who seeks some advice about a radio broadcast he’s done that a station won’t air because of fear that the FCC will deem it obscene (the poet’s brushes with obscenity charges predate those of the comedian).

Bruce, ever preparing appeals of his cases, is in full pontification mode. He leads his listeners into a veritable thicket of legalese, with much citing of precedents and mentions of not only the first amendment, but also the fifth and fourteenth. One can feel Ginsberg disengage; he politely declines to follow his host into the thorns. Much needed comic relief comes as Spector recounts to Bruce that he made a trek to Jungle Land to check out a possible opening act for the comic’s impending show: a trio of dancing pigs.

It’s Ginsberg who was taping the conversation. He leaves the recorder on as the men leave the house, and comments that Bruce’s house in the hills is a pretty setting in which to meditate on the law. He turns the machine off, then on again. As pragmatism and poetry unite, Ginsberg dutifully identifies the time and date of the encounter, adding that it took place “at the embattled, barbed wire household of Lenny Bruce.”

Lenny Bruce’s embattled, barbed-wire existence ceased not much more than six months later. The voice that came through my earphones for all those days was silenced. I would love to have heard it mature into middle- and old age. The world would have benefitted from many more years of Lenny Bruce, not only for his unique brand of schooling, but for the millions more laughs with which he would have gifted us.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

I was a senior in high school when the album Lenny Bruce American came out. And yes, it was red vinyl instead of the usual black. By the time I saw him perform at the Renaissance on the Sunset Strip, I probably knew many of the routines by heart.

Yes, Lima Ohio, Shelley Berman and Father Flotsky were favorites, but his riff on racism, “A Typical White Person’s Conception of How to Relax Colored People at Parties”…is a triumph. In the space of a few minutes, Lenny Bruce eviscerates any defense of racism by showing the ignorance and stupidity of prejudice and makes the point stick by using every cocktail party cliche and stereotype of the moment.

Sixty years later, Lenny Bruce American is as relevant as ever.