Theater Review: “Driving Miss Daisy” — Bypassing the Deeper Resonance

This production of Driving Miss Daisy isn’t about conflict and irresolution, but sentimental reassurance.

Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Ury. Directed by Howard Millman. Presented by Peterborough Players, 55 Hadley Road, Peterborough, NH, through July 3.

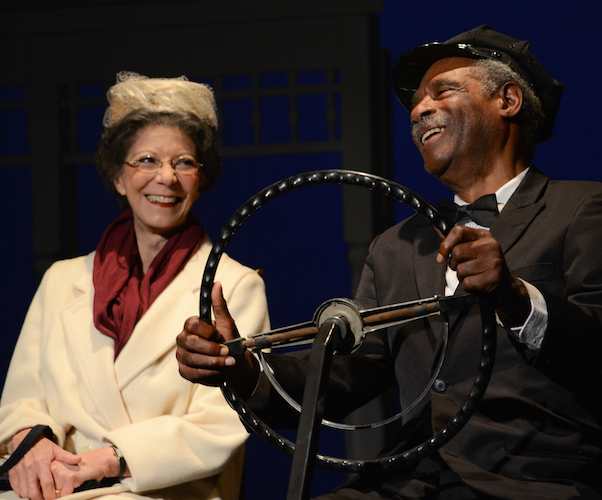

Carolyn Michel and Taurean Blacque in the Peterborough Players production of “Driving Miss Daisy.” Photo: William Howell.

By Jim Kates

On its surface, Alfred Uhry’s Miss Daisy presents a white liberal’s wishful Never Was. The script tries to forge an honest 25-year friendship between an elderly white Jewish woman in Atlanta and a black gentleman of similar age whom her son hires as his mother’s chauffeur in 1948. Vignettes loosely strung together span a turbulent couple of decades in the history of the American Southland — events that are touched on just enough to spice up the relationship without disturbing it. In these days of historical awareness and current social criticism, Driving Miss Daisy, first offered in 1987, has become a kind of period piece.

To make Driving Miss Daisy succeed as drama, a production has to bring out the countercurrents underneath, crafting complex characterizations that play against the Bless-Your-Heart gentility that masks real life in the Deep South even today, a gentility that propelled the paddle-wheels of social interaction when segregation ruled.

The performances that kick off the eighty-third season of the Peterborough Players hit all the top notes, but don’t try at all for deeper resonance.

We first meet Hoke Colburn (Taurean Blacque) at his job interview with Miss Daisy’s son Boolie Werthan (Kraig Swartz). In this version, Colburn displays no guardedness, and Werthan no condescension. Even without a racial component, this scene comes across as oddly complacent. It sets the comfortable, business-like tone for the rest of the play. When tensions of class or race arise, they are brusquely disposed of either by sentiment or by closing off that particular vignette and moving on to the next episode. At even the warmest sentimental moment of the play, its final gesture, we are not allowed to forget that Hoke is a servant, quite explicitly being paid by his master and literally serving his mistress.

If the script has set the rules of this game, the director Howard Millman has neither challenged them nor played the corners. It’s a straight run down midfield, and the team plays it that way.

Please don’t get me wrong: I’m not missing an anachronistic twenty-first century anger here, but searching for appropriate mid-twentieth-century repression, reflections of a time when even the simplest of transactions — a handshake, say, between black and white Southerners — could be fraught with implication and danger, much less a discussion of a bombed synagogue or Dr. Martin Luther King.

I have no doubt, from the quality of the performances they do give us, that all three actors are capable of far more edginess than they’re asked for.

Carolyn Michel’s Miss Daisy ages gracefully and beautifully. If the play has any arc of narrative, it’s one of her growth, but the growth should not be simple, spoon-fed as it were. She ought to move from independence to acceptance without indifference, and this Michel fulfills. Along the way, her character is drawn closer to her driver’s experience, but in her lines or actions she never quite gets to the liberal ideal expressed by Hoke’s “How you know the way I see ‘less you lookin’ out of my eyes?”

And yet Hoke is not talking there, as he has elsewhere in the play, about not being able to use a bathroom on a long road trip, or recalling a childhood lynching, but simply referring to his own failing vision and his ability to keep on driving. Blacque, portraying a figure of constant and consummate dignity, fails to convey Hoke’s consciousness of the slights and indignities that have kept him illiterate into his 70s and brought him to the Werthans’ service.

As Kraig Swartz has been moving into more mature roles, he is at his very best when he is most serious, leaving the mannerisms of his waggish youth behind. The scenes in which his Boolie Werthan come alive are those in which the character has most at stake. In fact, for brief moments of Driving Miss Daisy his Boolie appears to be the pivot of actual dramatic crisis, forced to confront at least a little of the reality around him. If we don’t like some of the choices Boolie makes, that’s not Swartz’s fault. The script and the director have made his most characteristic act one of repeatedly walking away.

This production of Driving Miss Daisy isn’t playing to an audience that wants conflict and irresolution. They want the liberal vision and they want the sentimental reassurance of good will — not grit and vinegar, but grits and molasses. With this opening production of the Players, that’s what we get.

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Muddy River (Carcanet), a translation of verse by Russian existentialist Sergey Stratanovsky. His translation of Mikhail Yeryomin: Selected Poems 1957-2009 (White Pine Press) won the second Cliff Becker Prize in Translation.