Book Review and Appreciation: Murray Talks Music, and So Much More — the Legacy and Lessons of Albert Murray

Before Murray Talks Music, there was little in print of Albert Murray as spontaneous orator. This new collection corrects that problem and shows how brilliant he could be even when he didn’t have time to polish his prose.

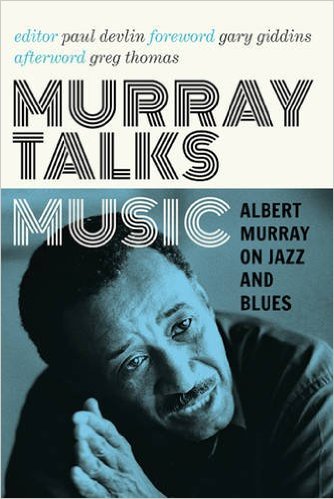

Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues, edited by Paul Devlin. University of Minnesota Press, 320 pages, $29.95.

By Steve Elman

A few more rounds with our old friend Al: that’s the tone of Murray Talks Music, a new Albert Murray collection, just in time for his 100th birthday, framed by appreciations from its editor, Paul Devlin, and critics Gary Giddins and Greg Thomas.

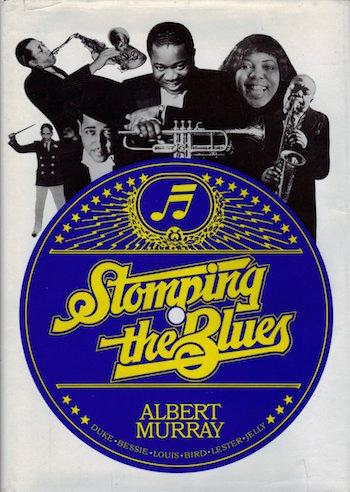

But what if Murray wasn’t your old friend? Worse, what if you’ve never read Stomping the Blues, the greatest work of jazz literature ever? Well, then, you are much poorer in soul — and before you buy Murray Talks Music, you need to start with his masterpiece, his Fifth Symphony, his “Love Supreme,” his “Sgt. Pepper.” There’s a keyhole in your mind into which Stomping the Blues will fit perfectly, and reading Murray’s remarkable rhapsody of words will open a door of perception that will make you — and I really mean this — a better person.

Maybe you vaguely remember some of the obits for Murray in August 2013. The ink-stained wretches struggled mightily to find a way to shrink his life and work into a few words. “Writer” is so bland and empty, but it was a reliable fallback for many of them. Some pointed to his importance in the civil rights movement, which represented a good news peg. Mel Watkins in The New York Times used “scholar” and “essayist, critic, and novelist.” James Campbell in The Guardian followed the paper’s idiomatic British style and let the man’s accomplishments speak for themselves.

So, if you want an introduction to how and why Murray was important, Watkins and Campbell will give you that introduction. But no summary can speak the way Murray spoke, and nothing Murray wrote conveyed his genius better than Stomping the Blues.

I remember picking up a paperback copy of the book in the late seventies, a few years after it came out. I knew nothing of its author, but I was struck by the cover, adorned with a vibrant blue-and-yellow imitation of the extravagant labels from 78 rpm records in the twenties and thirties, with photos of Louis Armstrong, Lester Young, Bessie Smith, and Duke Ellington bursting through the top arc, and Charlie Parker and Jelly Roll Morton off to either side. On the back, there was Murray, smiling genially above the same blue circle, his hands resting elegantly on his old typewriter. Inside, I saw that the design concept had been carried through on every page, with impeccable choice of typeface, beautifully reproduced photographs, and plenty of those vintage record labels. No wonder this credit appeared on the front cover, as was absolutely right: “Produced and Art Directed by Harris Lewine.”

And then came the first words of the text. No one had ever written about the blues like this, and I doubt that anyone ever will again:

Sometimes you forget all about them in spite of yourself, but all too often the very first thing you realize when you wake up is that they are there again, settling in like bad weather, hovering like plague-bearing insects, swarming precisely as if they were indeed blue demons dispatched in their mission of harassment by none other than the Chief Red Devil of all devils himself; and yet perhaps as often as not it is also as if they squat obscene and vulturelike, waiting and watching you and preening themselves at the same time, their long rubbery necks writhing as if floating.

“It’s Faulkner,” I thought. “It’s Faulkner writing about the blues. Who IS this guy?”

But that was only the start. Murray’s great themes emerged gradually, every one stated as if it was gospel and Murray had only come down from the mountain to deliver it: Blues music is core to American existence. Its purpose is not to wallow in sadness, but to drive that sadness away. The flipside of the dancing blues at the Saturday Night Function is the gospel music at the Sunday Morning Service. The blues provides the foundation for the profundity of jazz, just as folk art underlies all fine art. The blues musician, like every one of us, is a hero, improvising his or her way through the briar patch of life, accepting that struggle is inevitable but surrender is never an option.

Although Stomping the Blues is the only Murray work that you MUST read, it should whet your appetite for more. You’ll probably want to read some of his writings on the cultural rifts in America. The Onmi-Americans has dated a bit since its publication in 1970, but many of its insights are as profound as ever. Murray could be as fervent as any Black Lives Matter organizer when he denounced injustice and double-standards. But he also thought that Americans descended from slaves ought to think of themselves as heroes, not victims, and that they ought to embrace the identity of fully-vested Americans, not that of a people apart. He saw the issue as Keegan-Michael Key has seen it: an issue of culture, not color. And he went further, eschewing the label “African-American” – asserting that it implicitly accepts the subordinate place that people who are not “brownskins” want to impose. He urged all Americans, whatever the level of melanin in their skins, to accept that we all carry cultural DNA from our European, African, and “frontier / Indian” ancestors, and denying any part of that mix denies something essential about our Americanness. (I think he’d agree with Don Van Vliet, aka Captain Beefheart, when he said, “We’re all colored. Otherwise, we couldn’t see each other.”)

The themes in The Onmi-Americans and Stomping the Blues appear again in Murray’s essay collections, like From the Briarpatch File, and the eloquent and well-wrought prose that make so much of his work worth reading is on display in his short pieces as much as it is in his long ones. Those themes are in the new book as well. But before Murray Talks Music, there was little in print of Albert Murray as spontaneous orator. This new collection corrects that problem and shows how brilliant he could be even when he didn’t have time to polish his prose.

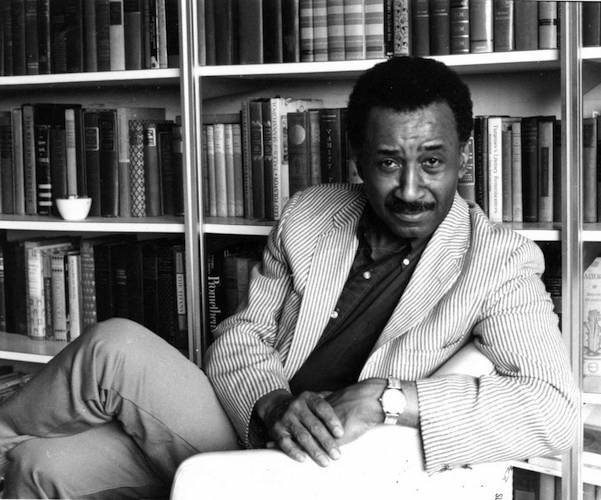

Albert Murray — The book is akin to those home movies that families treasured before everything we do or say could be recorded. Photo: Columbia University

The book is akin to those home movies that families treasured before everything we do or say could be recorded. They offer moments in Albert Murray’s life when he was talking beautifully about the things he loved, jamming on themes he had explored more formally elsewhere, and sharing good times with friends and colleagues.

There are nineteen of those clips: eleven transcriptions of verbal interactions with one or two other people, two previously-unpublished sets of notes, Devlin’s slight revisions of two previously-published items, and three published pieces which have long been unavailable. Each has an informative headnote to put it in context. Some are just like fragments from those home movies — they begin in the middle and stop without any sense of ending. A few are complete and precious artefacts – an extended interview with Dizzy Gillespie from the mid-1980s, a transcription of Murray’s appearance on “The Diane Rehm Show” in 1997, and, best of all, a three-way conversation with Loren Schoenberg and Stanley Crouch about Duke Ellington from a 1989 radio show on WKCR in New York.

Maybe we don’t need to be reminded quite so often about Murray’s seminal relationship with Jazz at Lincoln Center. And maybe we don’t need the glimpses of Murray the awed fan that we get in his conversations with Gillespie and Billy Eckstine — but then, who wouldn’t feel abashed being able to sit in the same room with Diz or with Mr. B?

There are three reverential appreciations — a foreword by Giddins, an afterword by Thomas, and an introduction by Devlin. Between the lines, they even gloat a bit: we knew him, we were there, we were “his guys.” I never had the pleasure they did of experiencing the man in person, of listening to him improvise verbally, so this collection often had me smiling with vicarious enjoyment, and occasionally shaking my head in wonder. As I finished, warmed again by Murray’s joie de penser, his joie d’écouter, I felt a bit of envy at their closeness to the flame.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: "Murray Talks Music: Albert Murray on Jazz and Blues", "Stomping the Blues", Albert Murray, American jazz, blues, Paul Devlin