Theater Feature: Willing Suspension Productions Celebrates “The Sea Voyage” and a Glorious Anniversary

Willing Suspension Productions serves as a valuable counter-balance to American academia’s Shakespeare-centric curriculum.

A scene from Willing Suspensions production of “A Mad World, My Masters.” Photo: courtesy of Holly Schaaf.

By Holly Schaaf

On April 21-23, Willing Suspension Productions will perform Massinger and Fletcher’s 1622 play The Sea Voyage at Boston University’s Student Theater at Agganis Arena. WSP, a company specializing in rarely performed Renaissance drama, is run by graduate students from BU’s English Department. This year’s production was scheduled to coincide with the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, but WSP is also celebrating an anniversary of its own – it has been ten years since the revived company’s first performance in 2006.

Willing Suspension Productions was formed in 1992 but ceased operation when the students involved completed their degrees In fall 2004, a key scene in the company’s history took place – yet it did not happen onstage. William Carroll, a BU English professor who helped found WSP, brought to his graduate seminar in Jacobean Culture a skull with lipstick that had been used as the remains of Gloriana in WSP’s production of The Revenger’s Tragedy. We were transfixed. Gloriana has numerous associations in the play, with other plays, and with the period, but in that moment she represented the existence of an amazing company that we suddenly realized we had the power to revive. As former director Kristin M.S. Bezio said of Carroll, who remains WSP’s faculty advisor, “He was the one who got us to start talking about it, and once we got talking, the company took on a life of its own again.”

Bezio, Liam Meyer, and Matt Stokes played pivotal roles in the company’s revival, combining their diverse and considerable talents to serve together as directors. Despite collective enthusiasm, we wondered if WSP would live beyond us. With the arrival of Emily Gruber Keck, who would go on to act, design sets, and direct, we were relieved. Gruber Keck says the WSP influenced her choice to enroll at BU: “Jen Airey showed me around campus, selling me on the group. During that visit, we ran into Kristin, who unlocked one of the closets and showed me the swords. My fate was pretty much sealed.” Still involved with WSP, Gruber Keck connects the first generation of the revival and recent directors Alex MacConochie, Devin Byker, and Julia Mix Barrington. The company creates deep bonds among graduate students, as well as between those students and WSP’s many undergraduate actors. Carroll explains that “graduate school can be isolating and alienating for some, and WSP brings people together.”

Carroll also stresses the importance of ongoing support from the BU Center for the Humanities (formerly the BU Humanities Foundation). WSP has been given word of its funding for the 2016-2017 academic year. But back in 2006, before the company was able to secure the Student Theater at Agganis Arena, the cost of performance space meant that a set, props, and costumes had to be assembled on a shoestring budget.

The success of Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Maid’s Tragedy, the revived company’s first production, hasn’t weakened memories of the company’s initial problems. Meyer recalls a major set piece made of scrap wood: “That first year, I built the amazing Fort! The unconquerable tower of Rhodes! I was proud of that fort—eight feet tall, yet moveable, and it had metal that looked like steel girders, so it seemed formidable. But in retrospect, as Matt pointed out, we could have spent more time on the bed. The King of Rhodes, apparently, likes to meet his paramours on a dinky twin-size bed. That right there gives an indication of some of the challenges we faced.”

The company’s 2007 production, Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II, contained several scenes that were pivotal to the play but difficult to stage. Bezio remembers one risky episode: “We had a full battle with sixteen armed actors that was hopefully not going to lead to actual bloodshed.” Part of this scene’s success came from Bezio’s lighting design at the climactic point when the actors charged. As the seasoned technical director recalls, “We flashed lights in the faces of the audience at the climax so that the actors could run offstage without being seen even a little bit—it also made everyone jump in their seats.”

Wonderfully shocking to Edward II audiences as well was the decapitated head of Mortimer, a prop made by Bezio’s husband, Kirk. “We made a life-cast of the actor who played Mortimer,” she revealed, “In the final scene, when another actor carried out a basket and pronounced, ‘Here is the accurséd traitor’s head!’ people chuckled, until he reached in and pulled the head out by the hair, with blood (corn syrup and food coloring) dripping thickly from the neck. Then they were grossed out.”

A scene from the William Suspension production of “The Changeling.” Photo: courtesy of Holly Schaaf.

After The Maid’s Tragedy and Edward II, WSP embraced comedy with Thomas Middleton’s A Mad World, My Masters. At this point they began to experiment with setting plays in different time periods. Meyer observes that setting Mad World in the 1950s made sense because “the play is all about the sexualized antics and anti-social impulses that lurk beneath a surface that is ostensibly straight-laced.” Bezio makes a similar point about how the sexual repression in Middleton and Rowley’s The Changeling (performed in 2010) worked well in a Victorian setting, also noting that the production used a real straight jacket. Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair “had too many modern analogs for us to do anything but a 1980s/1990s state fair,” according to Bezio. The 2013 play, John Fletcher’s The Tamer Tamed, is a sequel to The Taming of the Shrew a battle of the sexes that was a natural for a production set in the 1960s. Devin Byker’s catchy sound design and Stephanie Brownell’s costuming were essential to capturing the mood of that period. Gruber Keck mentions that setting Arden of Faversham (2014) in the 1920s was driven by the gap between the wealthy Arden and those he exploited: “We wanted to make that legible, and ‘Occupy Wall Street’ seemed too on-the-nose, so we went with an earlier era with drastic income inequality.”

Gruber Keck explains that Renaissance drama lends itself to adaptation: “All those versions of ‘Venice’ and ‘France’ and ‘medieval London’ are metaphors for sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. The instability is built-in because the playwright is already inviting — and relying on — the audience to ignore the dissonance between language and time/place. That gives twenty-first century directors fantastic opportunities to make that instability work for them.”

Shifts in period helped make possible memorable props and sets. As Bezio recalls, setting Mad World in the 1950s “let us have fun with twinkies and jello molds. Jello, for what it’s worth, does not hold up terribly well under stage lights, but it does jiggle and glow impressively.” The Dutch Courtesan, staged in 2009, boasted an immense fish purchased at Haymarket. Clocking stage time from dress rehearsal through closing night, the fish rested between performances in various directors’ freezers, and was affectionately dubbed “Mr. Stanky” by the crew. A less pungent but crucial element of that production was a streetlight that was used to distinguish different locations without the assistance of set partitions. “I was happy with that streetlight,” Bezio exclaims, “since I had to take an exterior house light and wire it by hand into a theatre-three-pin system — and I didn’t electrocute anyone, or burn anything down!”

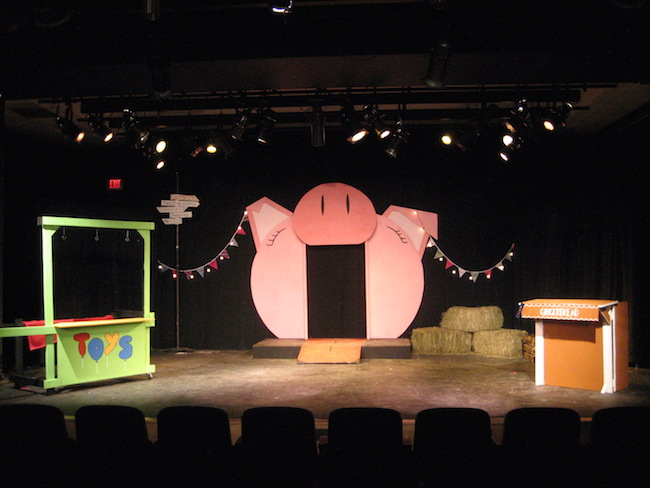

The revived company, from its beginning, had aspired to perform Ben Jonson’s Bartholomew Fair, his expansive masterpiece about consumerism, art, hucksters, puritans, and summer fairs. Year after year we wondered if we were ready. In 2011 a production was mounted and it was a triumph. The play included gingerbread houses built by the actor who got to smash and eat them on stage every night. There was also an exceedingly elaborate puppet show. Gruber Keck designed a giant pig face set with a tongue for a ramp, as well as the booth at which she presided as Ursula the pig woman, a massive character in the play’s enormous, multifarious cast.

Though she played other major roles for WSP, debuting as the Courtesan in Mad World who has to talk and cough through the most outrageous scene in the play to conceal the loud sex noises of two other characters, Gruber Keck confesses that her ” most vivid memories as an actor are definitely Ursula. There was a huge physical challenge — trying to convince the audience that I was an older, overweight woman — and, in the actual performances, trying not to pass out from the heat of the fat suit! But that was also the first role where I had trouble memorizing lines. I can memorize iambic pentameter quickly, sometimes against my will, but Jonson’s language is so crazy and rhizomatic that it wouldn’t stick in my brain. And when it did stick, finding the humor in it and conveying it to the audience was a challenge.” Of the play, she admitted, “I’m still a little in awe that we pulled that show off — it’s a tribute to the whole cast and the directors that the audience laughed almost constantly through the whole thing.”

WSP’s success performing rarely staged plays has made the power and necessity of the company’s existence clear to audiences and to the directors themselves. Stokes explains that witnessing performances “drives home the fact that a play-text is primarily intended as a skeleton for a much more complicated, collaborative work of art.” MacConochie agrees, “The plays are meant to be performed, so seeing them live is seeing them in their natural habitat.”

Meyer points out way in which performance aids and abets understanding: “When you are reading and you come to a joke about someone’s status, any critic worth their salt will get the gist of the joke. But actors onstage want to know specifically how and why a joke is funny, and what their character’s response would be, and why. You have to ask yourself whether the middling-sort urban innkeeper with pretentions to Puritanism on stage left will be laughing or scowling, and whether the nouveaux-riche aristocrat just arrived from the country over stage right will feel slighted or not.”

The set for the Willing Suspension production of Ben Jonson’s “Bartholomew Fair.” Photo: courtesy of Holly Schaaf.

“We’ve worked with so many talented students over the years,” Gruber Keck says excitedly, “and they bring many great insights into characters I’d never come up with — I try to watch for those in rehearsal, and challenge actors to do more. I don’t want the show onstage to be a representation of my thoughts about the text, because that won’t be nearly as interesting.” Mix Barrington elaborates: “It’s a challenge and an opportunity for actors to try to inhabit characters that are around four centuries old. They have to figure out what’s recognizable in those people. If the actors understand what they’re saying and the connotations, they’ll pass that along to the audience. But the language is unfamiliar. We don’t want to back away from that — we want to lean in!”

In addition to the dynamic interactions between actors and directors, collaborations between co-directors also confirm the value of working together to bring these texts to life. “Every director I’ve worked with, including my co-directors, has had a different perspective on the set than I have,” Gruber Keck reveals, “Matt in particular is in love with very symmetrical, very bare-bones sets, and I spent years pushing back at him. But those tensions ultimately resulted in great sets.” Co-directors have also trusted each other’s instincts when it comes to making the most of particular plays in performance. “When I read The Shoemaker’s Holiday, I had to take Alex and Emily’s words that it would work onstage,” Mix Barrington concedes, “It wasn’t until we started rehearsing that I really understood what the play was doing — and understood that it’s a masterpiece. Without WSP, I could have gone for years missing out on that.” The diverse directors and their different passions have enabled the company to experiment with an exciting range of approaches and share with thousands of audience members the vibrant humor and deeply human emotion in these long neglected plays.

Beyond bringing these remarkable performances to audiences, the directors’ experiences have also influenced their classroom practices, and work with WSP has shaped the teaching of other former members of the company as well. Jennifer Airey, now a professor of English at the University of Tulsa, stresses the importance of performance for undergraduates studying literature: “Students often don’t realize the difference between reading and watching a play. By encouraging them to watch or perform, you can reveal the extent to which interpretations are dependent on acting choices and vocal inflections. When you get students into costume, they can feel how people in the period moved, how their bodily realities would have shaped their world views.”

The company’s productions also enhance our understanding of Shakespeare while expanding our knowledge of the period’s drama beyond his work. While not ruling out the possibility of the company performing Shakespeare, Carroll emphasized the importance of WSP as a counter-balance to a US English curriculum that is Shakespeare-centric, a fact the company’s directors acknowledged when discussing their early interests in drama of the period. “Shakespeare has been naturalized for us,” MacConochie reflects, “And Shakespeare is of course great, but the strangeness of these other authors’ plays can give a new perspective on issues that Shakespeare gives short shrift to. Last year we produced Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday, which gives a view inside the lives of London’s working class that is respectful and empathetic — something that, arguably, Shakespeare never spends much time on.”

Bezio stresses that actors, directors, and audiences can come to non-Shakespearean plays without preconceptions of how they’ve been staged before, a sentiment Meyer echoes: “I love Shakespeare, but there are hundreds of other plays from that period. Seeing a Renaissance play you have no preconceptions about allows you to be carried away by the language because you can be genuinely surprised. I love watching a good production of Hamlet, but I’m always ready to hear Polonius behind the arras. So it’s been a real treat for me, now that I’m ‘retired’ from WSP, to see a play that I barely know each year.”

Gruber Keck, considering the broader implications of WSP, adds: “Shakespeare dominates conversations about early modern drama, but he didn’t exist in a vacuum, any more than any novelist or playwright writing today. He was competing with other people, who influenced him and who he frequently influenced; he stole from them when they innovated and vice versa. Without attending to other early modern dramatists, the conversation about Renaissance drama is incomplete.”

A scene from the Willing Suspension Production of “Edward II.”

The conversations WSP creates extend beyond Boston University, the city, and the region. Carroll emphasizes how WSP enables students and faculty to see plays that they would not otherwise see performed. “I had seen only a handful of their plays performed, invariably in England,” he remarks, “WSP’s existence also enhances, as one would expect, the reputation of the BU English Department in the region: faculty from as far away as UMass/Amherst (and, during the 2012 Shakespeare Association of America meeting in Boston, across the country) have come to campus with their students to see productions.”

Though there is no substitute for witnessing a live performance, WSP further extends its reach through twenty-first century technology. Starting with Mad World, WSP filmed their productions and made them available on BUniverse, a platform for videos of campus events.The plays have since migrated to YouTube, which resulted in scholar Pascale Aebischer discovering the company, interviewing its members, and including WSP in her 2013 study Screening Early Modern Drama: Beyond Shakespeare.

Anyone can now watch the productions on YouTube, and while the company welcomes the broad audience, its members also hope that WSP inspires more scholarly work. Mix Barrington emphasizes her excitement about what she calls “‘Forensic theatre’ — the idea that casting and blocking and rehearsing and performing these plays is scholarly research. Many WSP plays haven’t been done in the US for centuries, or ever. People who study them could get a lot of information from our performance videos.” Gruber Keck chimes in, “If performing The Dutch Courtesan or The Shoemaker’s Holiday prompts even a few people who watch the shows to write about or otherwise engage with the wealth of plays out there, we’ve made an invaluable contribution to early modern scholarship!”

Thanks to the current directors, WSP’s crucial contributions will continue. Passionately fascinated by the period, Mix Barrington hopes to build a closet of Elizabethan and Jacobean costumes to leave to WSP when she graduates: “I’m curious to see what these plays might have looked like when everyone was dressed with less of an eye to realism and more of an eye to impressing the audience. Early modern costumes were castoffs from powerful people — someone onstage may have been wearing an actual bishop’s robe or a gown that a court lady had been seen wearing in a previous season. We can’t recreate those connotations, but I am excited to approximate early modern staging: simple sets, and most of the glitz in the costumes. We’re working with a theatre graduate student at BC whose research is on costuming.” She is interested in collaborating with other local graduate students: “Nobody else is doing plays the way we do, and I think we can use that to strengthen the community of graduate students in the city.”

Mix Barrington and MacConochie excitedly note parallels between this year’s play The Sea Voyage and Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The co-directors organized a reading of The Tempest to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death and to warm up for WSP’s upcoming production. Of The Sea Voyage, MacConochie declares “It’s weird, it’s wacky, and stars pirates and their lovers. It’s a whole lot of fun!” Mix Barrington suggests, “It will appeal to a wide audience because it’s a combination of the expected – a love triangle and sword fighting – and the unexpected – an island of Portuguese women who have decided to live as classical Amazons after their shipwreck. Audiences should expect a light comedy about some dark subjects, with a good amount of swashbuckling adventure thrown in.” May Willing Suspension Productions continue taking audiences on adventures for many years to come!

Holly Schaaf, a lecturer in BU’s CAS Writing Program, was a producer, ticketing and house manager, treasurer, hauler of props, and WSP’s token Irish Modernist. She thanks everyone involved with WSP, especially those interviewed for this piece, and also Anthony Wallace for encouraging her to write for The Arts Fuse.

Tagged: Boston University, William-Shakespeare, rarely performed Renaissance drama