Jazz Review: Pianist Kenny Werner — Teaching “Effortless Mastery”

“The problem is that more people get lost going to music school than get found.”

An Evening with Kenny Werner and Friends at Berklee Performance Center, Boston, MA, on February 2.

Kenny Werner at the piano in the Berklee Performance Center. Photo: Berklee College of Music.

By Jason M. Rubin

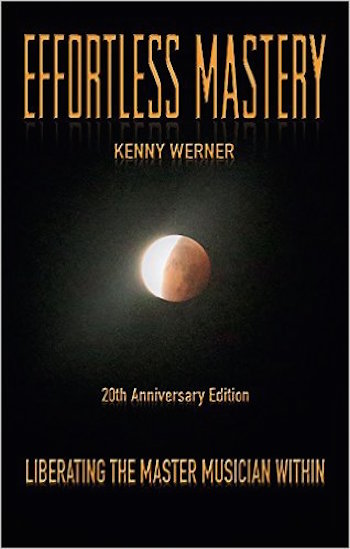

Show, don’t tell. That broadly applicable maxim was on full display at Berklee Performance Center recently, when jazz pianist Kenny Werner and his very gifted friends gave a riveting ninety-minute performance that was intended as a celebration of the 20th anniversary of Werner’s 1996 book, Effortless Mastery: Liberating the Master Musician Within. For the audience, however, there was a whole lot of incredible music to enjoy, but very little talk about the book. Which, I’m sure, no one there was particularly disappointed about.

I was fortunate, though, to have been invited to a pre-show reception during which Werner did do the telling. In fact, he didn’t even have the book itself to show, since printing problems with the new 20th-anniversary edition has led to a delay in its release. No matter, his remarks were illuminating and his performance only added additional light.

“There is a condition I call MSD: Music School Disease,” he explained. “The problem is that more people get lost going to music school than get found. They are blasted with concepts and are expected to advance at an unrealistic pace. Obsessed with playing well and surrounded by brilliant talent, they learn not to trust their own instincts.”

Compiling insights and ideas from his own life and career, he composed Effortless Mastery to help musicians heal themselves by broadening their perspective and exploring the spiritual, psychological, mental, and physical aspects of music making. And if that approach seems to be a slap at an institution like Berklee, bear in mind that Werner came to Berklee as a student in 1970. Furthermore, after a conversation with Berklee College of Music President Roger Brown, who was already a fan of the book, Werner was hired in 2014 to be artistic director of the College’s new Effortless Mastery Institute.

“In the Institute we get students to love their sound,” said Werner. “We encourage them to make mistakes, to play carelessly. They begin to understand where they really are as a player, and the fear goes away.”

Using a range of mind-body strategies, such as the Alexander Technique, body mapping, tai chi, and yoga, students in the Effortless Mastery Institute are taught to overcome obstacles that keep them from performing at their best.

“To play better you have to be healthier,” he said. “Some people give up a career as a performer to do music therapy; this is music therapy for the performer.”

Following the reception, the concert began with Werner entering the stage alone and playing a solo improvisation that incorporated “Somewhere” from the musical West Side Story. Werner, sympathetic to if not a card-carrying member of the Third Stream, has an endearing habit of raising his left hand at times to sort of “conduct” his right hand. He is a fluid player who shapes space as well as sound, employing sudden changes in tempo and dynamics.

After his solo piece concluded, Werner left the stage and his special guests Joe Lovano and George Garzone entered to play a tenor sax duet. Werner later noted that the three legends had known each other for some forty years, that they are “brothers” and “share the same breath.” That said, there was a compelling contrast between Lovano’s powerful yet breathy tone and Garzone’s more free and forceful delivery.

Werner then joined for a couple more tunes and then mentioned the book very briefly; chiefly, it seemed, to introduce all the players joining him that evening as “effortless masters.” With that, his trio mates for the last sixteen years, bassist Johannes Weidenmueller and drummer Ari Hoenig, came on stage. The full quintet then played the Werner composition “Ballad for Trane” with Garzone, Lovano, and Werner taking impressive solos.

The next few numbers (bouncing from Rodgers and Hart to Bach to another Werner original) featured just the trio of Werner, Weidenmueller, and Hoenig, yet the energy and invention didn’t take the slightest dip. Weidenmueller, looking every bit the refined and demure European, played acoustic bass with exceptional strength and articulation. Hoenig, scowling and disheveled — at times he looked scary enough to resemble a maniacal serial killer — was indeed a monster but a musical one, displaying remarkable speed and dexterity, never missing a single one of Werner’s unexpected accents and rhythmic and melodic left turns.

One final number with the full band, punctuated with exciting solos from Lovano, Garzone, and Hoenig, concluded the evening. Effortless? Perhaps. At least it looked that way. Mastery? Without question, which is why it looked so effortless. If one assumes that the book is the theory and the performance is the practice, then no other endorsement of the book need be given. Though the pages were absent, what happened on stage was a convincing celebration of the wondrous possibilities of musical expression.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for 30 years, the last 15 of which has been as senior writer at Libretto, a Boston-based strategic communications agency. An award-winning copywriter, he holds a BA in journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, maintains a blog called Dove Nested Towers, and for four years served as communications director and board member of AIGA Boston, the local chapter of the national association for graphic arts. His first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. He regularly contributes feature articles and CD reviews to Progression magazine and for several years wrote for The Jewish Advocate.