Fuse Remembrance: Bowie on Film — Ageless Enigmas

Bowie the Legendary Rock Star and Bowie the Fashion Chameleon were flashier, bolder, than Bowie the Cinematic Iconoclast; but his film roles add up to a remarkably impressive set of achievements.

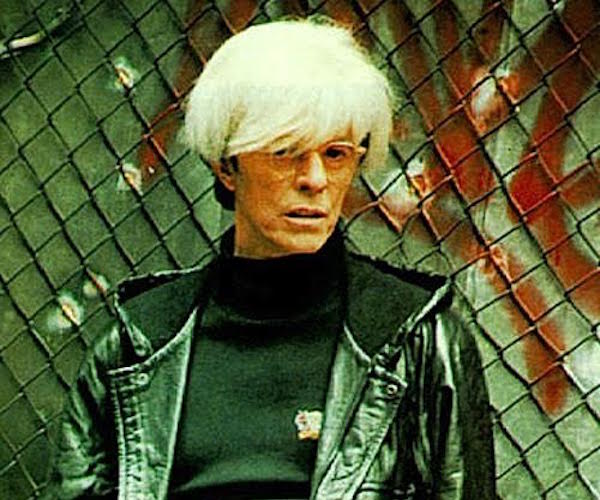

Bowie as Andy Warhol in “Basquiat” (1996)

By Peg Aloi

David Bowie’s film career spanned several decades and a range of genres, with roles embodying the same offbeat vigor as his colorful stage personae. Bowie the Legendary Rock Star and Bowie the Fashion Chameleon were flashier, bolder, than Bowie the Cinematic Iconoclast; but his film roles add up to a remarkably impressive set of achievements.

Much like the shamanic shape-shifting that defined his music career, Bowie’s cinematic roles loomed larger than life, even as his on-screen acting style was often laconic and minimal. His feature debut in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) established Bowie as a notable film talent, and set the tone for a string of performances in macabre-tinged films. When his characters were not actually supernatural, like John Blaylock in The Hunger (1983) or Jareth the Goblin King in Jim Henson’s Labyrinth (1986), they at least had an otherworldly or larger than life quality: a businesslike, cold Pontius Pilate (The Last Temptation of Christ); a subdued and humble Nikola Tesla in The Prestige; a childlike, befuddled Andy Warhol in Basquiat, or the mysterious Philip Jeffries in Fire Walk with Me.

These performances, along with Bowie’s stunning turn as a prisoner of war in Japan during WWII in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, comprise the most noteworthy roles in what has been a relatively prolific acting career, considering Bowie is first and foremost known as a musician. He also appeared on Broadway from 1980-‘81 as John Merrick in The Elephant Man, to rave reviews.

Playing Andy Warhol in Basquiat (Julian Schnabel, 1996) was perhaps one of the most inspired and perfect moments of film casting ever, given Bowie’s unforgettable song about Mr. Warhol from his Hunky Dory album in 1971. This is the only role where Bowie appears to be actually trying to play a character, as opposed to embodying one. There is a somewhat forced quality to the performance at times, but Warhol in Bowie’s skin is delightfully complex, sometimes so socially awkward it’s painful to watch, sometimes dominating a room with quiet humor and panache. In a 1983 interview for Musician magazine, Bowie said “As an adolescent, I was painfully shy, withdrawn. I didn’t really have the nerve to sing my songs onstage and nobody else was doing them. I decided to do them in disguise so that I didn’t have to actually go through the humiliation of going onstage and being myself.” These demons of his teenage years no doubt helped inform his work on this role. Alongside another inspired casting choice, his scenes with Dennis Hopper as art dealer Bruno Bischofberger are pure zeitgeist, two pop culture legends trying their best not to let us see the white hot energy beneath their sedate exteriors.

Just as fans of Bowie’s music have their favorite songs and albums (I tend to be drawn to the earlier works, including Hunky Dory, Aladdin Sane, Diamond Dogs and Ziggy Stardust), the film roles have their lovers and detractors. There is generational bias as well, perhaps, especially where Labyrinth is concerned, as the film was a popular favorite among those who came of age in the 1980s. Also, Bowie actually sings in the film, and rules over a spectral magical landscape, as well as sporting a flamboyant costume: what’s not to love?

Those of us who were past our teen years by 1980 were perhaps more moved by the vampire tale The Hunger, a glossy horror film with an excellent soundtrack ranging from Bauhaus to Bach. I first saw it on VHS, at the home of one of my college professors, a scenic designer. He invited a few of his students over to watch it, thinking we’d love it, knowing Bowie was a minor obsession for many of us. It had a dreamy quality that haunted me: I bought the soundtrack album at the local record store, along with a black and white poster of a still from the film, showing Bowie playing the cello. I sought the film out again and again over the years, at midnight movie showings and film archives, and it has never not been in my list of Top Ten Horror Films. In addition to the steamy shots of Bowie and Deneuve making out in the shower, The Hunger also garnered plenty of attention for the hot lesbian sex scene between Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon, whose lovemaking to the dulcet strains of Delibes’ “Lakme” forged an indelible connection for moviegoers, linking that music to Sapphic love, as seen in 1987’s quirky I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing.

David Bowie and Catherine Deneuve in “The Hunger”(1983)

But it’s Bowie’s portrayal of John Blaylock, lover of Miriam Blaylock (Deneuve), that makes this beautiful film so memorable for me. The story is not terribly straightforward, but we understand the two are vampires, and have been lovers for centuries. In the present day, these wealthy urban sophisticates spend their days playing music or reading; their nights are dedicated to trolling nightclubs and bars for willing prey. John suddenly begins to feel ill and tired, and realizes that, like the last lover Miriam had, he is doomed to age, while Miriam remains young. His anger and frustration are understated but palpable. He even tracks down a doctor (Sarandon) who specializes in aging, thinking a modern miracle might save him from an ancient fate. He ages quickly, but still needs to satisfy his hunger for blood.

Bowie portrays this fall into senescence with stunning depth and nuance, his lust and sorrow visible beneath no small amount of prosthetic make-up. There is a particularly unsettling scene where his character attacks a young neighbrhood girl because he is no longer strong enough to subdue an adult. When he realizes Miriam can no longer love him in the way she did when he was younger, her kiss now devoid of passion, John loses all hope: “Then kill me,” he says. But she can’t help him escape to the realm of death; he is doomed to be eternally alive in a body that continues to age and decay. She places him in a box, in a room filled with her previous lovers who have also met this fate since time immemorial. His endless days pass amid cooing doves and the sound of wind blowing through silk curtains.

I have found myself thinking about this film in recent days, watching clips of darkly brilliant characters in his final film art, music videos from Blackstar, as I muse on the passing of an artist whose talents and presence were so dynamic that he seemed somehow immortal. Of course, no one lives forever, but Bowie’s death at a comparatively young age, and marked by a new body of work that is drawing widespread acclaim, seems particularly cruel and pointless. And yet, the universe has a sort of kindness. It endowed this strange man with tremendous gifts, bore him along as he rose from outlier to demi-god, speaking truth to our misfit hearts. It then gifted us with the ingenuity to preserve and celebrate his art, so that its color, sound and unstoppable energy might remain with us, even as his spirit took flight, leaving traces of gold and turquoise in the ashes, fluttering like bright plumes falling to earth.

Peg Aloi is a former film critic for The Boston Phoenix. She has taught film studies for a number of years at Emerson College and is currently teaching media studies at SUNY New Paltz. Her reviews have appeared in Art New England and Cinefantastique Online, and she writes a media blog for Patheos.com called The Witching Hour.

Your blog post was really enjoyable to read, and I appreciate the effort you put into creating such great content. Keep up the great work!

This post came at just the right time for me. Your words have provided me with much-needed motivation and inspiration.Thank you