Book Review: Three Early Works from Sci-Fi Master Samuel R. Delany

By Vince Czyz

Taken together, these entertaining early novels present a noteworthy collection—particularly for Samuel R. Delany fans.

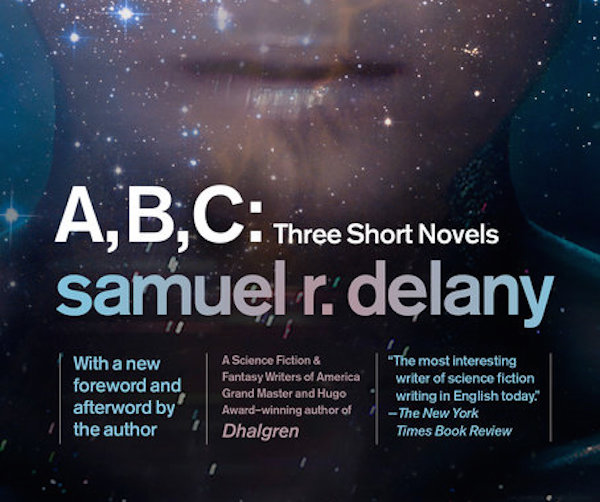

A,B,C: Three Short Novels by Samuel R. Delany. Vintage, 496 pages, $16.95.

In the early ’80s I was a bit of science fiction junkie. I read authors such as Isaac Asimov, Roger Zelazny, Ursula K. Leguin, Robert Heinlein, Poul Anderson, Theodore Sturgeon, and Samuel R. Delany—especially Delany—with devoted regularity. I was smitten by The Einstein Intersection, Babel-17, and, most of all, Nova, Delany’s novel about a crew of mismatched outcasts and their Ahab-like captain, Lorq von Ray, who is determined to take his ship into the heart of a disintegrating star. (I’m leaving out Dhalgren, Delany’s magnum opus, because I don’t consider it science fiction; after three readings, however, I have come to count it, without exaggeration, among the best novels of 20th century.)

I loved far-flung worlds, alien races and civilizations, interplanetary intrigue, technology raised to new magnitudes, and I was addicted to what seemed to me brilliantly imagined worldviews—or at least tantalizing glimpses of blueprints to alternate modes of seeing and even being in the universe, or perhaps the multiverse. Delany excelled at this.

I stopped reading more than the occasional science fiction novel about 25 years ago, so A,B,C: Three Short Novels by Delany, now universally acclaimed as a master of the sci-fi genre, was like splashing around in a waterhole I hadn’t dipped into since a long-ago summer when I was a teen.

A,B,C contains The Jewels of Aptor (A), The Ballad of Beta-2 (B), and They Fly at Çiron (C), which are indeed short but are also among Delany’s earliest endeavors. Aptor, in fact, was Delany’s debut as a novelist, written when he was 19 and published when he was 20. The plot is a fairly straightforward quest: centuries after the Earth has been scorched by “the Great Fire,” three men and a four-armed boy are charged by a high priestess with making the voyage to Aptor, a terrifying land of mutants and radioactive ruins, where they must steal the final, third jewel (she has one; the boy has another) and return with her kidnapped daughter.

Delany sets up a series of dualities, including a White Goddess (Argo) opposed by a dark god (Hama); a land that has regressed to swords, sails, and a vaguely feudal hierarchy (Leptar) menaced by an island of ancient but highly sophisticated technology (Aptor); institutionalized religion set against the phenomenon of religious experience; a theory of action based on dual motivations; and, the unified field underlying everything, chaos ensconced within order. All foreshadowed by an allusion on page two to the Chinese philosophy of duality embodied in the yin and the yang.

Urson, a cave bear of a man and an experienced sailor, is the expedition’s muscle. Geo, a poet, and Iimmi, a black sailor who, like Geo, is highly literate and well-schooled, are the thinkers in the foursome, while the boy, Snake, is a talented thief and telepath. The four make their way through Aptor, encountering a werewolf, a race of human-size vampire bats adept at wielding swords, ape-like scavengers with bronze claws, and a terrifying super-amoeba.

It’s a fun novel—not just the swashbuckling skirmishes and the eerie exploration of overgrown ruins—but also the mental chess Geo and Immi engage in to ascertain the motivations of those around them, including the high priestess who sent them on their quest, and to deduce who among them is a spy for Aptor. Clearly, however, Aptor is early work. The dialogue is sometimes stilted; there are a couple of places where the plot doesn’t quite hold up; and the writing is somewhat uneven. But none of these flaws is fatal, and the prose is often sharp, indeed, as when Delany describes Snake using a jewel to fend off the giant bats:

Fire leaped from the boy’s hands in a double bolt that converged among the dark bodies. Red light cast a jagged wing in silhouette. A high shriek, a stench of burnt fur. Another bolt of fire fell in the dark horde. A wing flamed, waved flame about it. The beast tried to fly, but fell, splashing fire. Sparks sharp on a brown face chiseled it with shadow, caught the terrified red bead of an eye, and laid light along a pair of fangs.

I also found the big reveal, which speculates on horror as a component of Zen-like illumination, somewhat unconvincing—if ingenious. But the fact that Delany even descended into the murky nature of religious experience sets the book well apart from the pulp that ballasts much of the genre.

The Ballad of Beta-2 is a very different novel. Joneny, a brilliant anthropology student, has an assignment forced on him by a demanding professor: the historical analysis of a ballad intimately connected to the enigmatic disaster that befell a fleet of colonizing starships. The ships, with names such as Sigma-9 and Beta-2, left Earth centuries earlier but arrived at their destination, the Leffer System, long after it had already been colonized (thanks to the invention of hyperdrive). Of 12 ships, only 10 reached Leffer, and two of those were empty hulks wrecked by some unknown force. The novel is futuristic detective fiction whose primary clue is an old folk song—a nearly irresistible set-up.

The story hits bumps when Joneny sets out, alone, to board one of the derelict starships. “There was no difficulty in identifying it as Sigma-9. It looked like a crushed eggshell, with a fine spider-webbing of girders feathering the edges of the cracks.” When he arrives, the ship is devoid of human beings—there aren’t even a few token guards to make sure college kids like Joneny, who have the same access to spaceships contemporary teens have to cars, don’t throw frat parties in the massive relics. It seems more than passing strange that the ships have not been turned into a tourist attraction, a museum, or at least the focal point of research for numerous anthropologists (Joneny’s protests that the Star Folk, as they are called, are backward and unoriginal notwithstanding). It also strains credulity that Joneny encounters a child with astonishing powers—teleportation and the ability to live quite comfortably in a vacuum among them—but no one else seems aware of such a being (beings, as it turns out).

Once we get beyond these issues, however, it is deeply engrossing to watch Joneny reconstruct—from fragmentary ship records, testimony from the wunderkind, and clever literary analysis of the song—what happened on the ill-fated journey through deep space.

Joneny discovers—a little conveniently—that several generations out, a species of religious fanaticism took hold, marginalizing or exterminating “citizens” of the ships (which are referred to by inhabitants as “Cities”) who were mentally or physically aberrant. “Our ancestors charged us with bringing human beings to the stars and no deviation will be tolerated,” insists the judge of a quasi-religious court. Here we find a tie-in to Aptor, which suggests that religious enlightenment is a worthy enough aspiration, but an evangelical, rigidly imposed religion is a horror on par with a new strain of bubonic plague. And, indeed, Beta-2 implies that the Star Folk are utterly backwards and their culture stunted because they allowed religion to supplant intellectual curiosity, new ideas, variant forms—the new and different in general.

One of the most ingenious aspects of the story is a zero-gravity section of the ship to which deviants naturally migrate: “It’s pointedly obvious that this section of the ship was not intended to be lived in … the hidden ways and mechanical niches and paths are never used by the people of the City.” The urban analogy is clear: a shanty town, a ghetto, an open-air prison. This unofficial district is a concept that echoes throughout Delany’s work. In Trouble on Triton it is called the Unlicensed Sector. It reaches its most detailed and eloquent expression in Dhalgren, in which an entire Midwestern city, in the absence of any police, military, or judicial system, evolves its own unwritten rules and codes of behavior.

Author Samuel R. Delany—in these entertaining early short novels fans will find in embryo many of the motifs and themes that are more fully articulated in later works.

In terms of the writing, Beta-2 is more polished than Aptor, but there’s only one real character in Beta-2, (Joneny). The runner-up is a figure vaguely resurrected from the history Joneny recreates: Leela, a starship captain. When a mysterious force begins destroying the ships, she confronts a deep-space entity apparently connected with the unfolding catastrophe. So while Beta-2’s premise is somewhat more sophisticated than Aptor’s, Beta-2 is lacking in one of Aptor’s mainstays: character interaction.

They Fly at Çiron was Delany’s second attempt at a novel but was rejected by his publisher. Many years and revisions later, it became his 19th novel to see print. The kingdom of Myetra is led by Prince Nactor, a ruler hell-bent on empire who enforces if not a scorched-earth strategy, certainly a scorched-population policy. Çiron, an idyllic village whose people probably don’t even have a word for weapon, is the next on his hit list.

The book opens with Nactor’s brutal execution of prisoners taken in a recent battle. His second-in-command, Lt. Kire, pleads for leniency, but Nactor denies his request. “Smells like barbecue,” asks the nasty prince, “doesn’t it?” This sets up the dynamic between the two men that persists throughout the novel.

Rahm, a rather bad-ass villager who kills a mountain lion in hand-to-claw combat, escapes the initial slaughter and destruction of Çiron, and through luck, pluck, and handiness in a brawl, becomes a favorite among the Winged Ones, an enigmatic race of what are essentially human-like bats powerful enough to carry aloft physical prodigies like Rahm. One of the most interesting twists in the book is that the other leader of Çironian resistance is the village garbage collector, Qualt. While Rahm is mostly brawn, Qualt gets by on cunning and guile. Whereas Rahm was always popular in the village, the villagers take notice of Qualt only after Myetra’s ruthless assault.

Delany complicates the story by making two grunts in Myetra’s army key characters. One of them, Uk, is clearly enough a decent man trapped under the command of a hideous autocrat. There are no easy ideas of good and evil in the novel: Uk fights because he’ll be executed if he doesn’t (as well as to defend his best friend, another soldier, and his countrymen). Rahm fights to protect home, family, and friends but must confront the consequences of his actions, however defensive. The Winged Ones are drawn into the fray, but they prove to be an ambiguous force, and Kire, always at odds with Nactor, considers outright betrayal. Rahm and Uk form a kind of symmetry in which Delany implies circumstances alone are capable of engendering unreasoning, murderous fury, even in a man like Rahm, who has never before killed another human being. Here, as in Aptor, it is clear that dualities are never clearly delineated—the potential for one always exists within the other.

Taken together, the novels present a noteworthy collection—particularly for Delany fans, who will find in embryo many of the motifs and themes that are more fully articulated in later works. But each novel is entertaining in its own right, and each is a reminder that the ability to imagine other worlds in depth and detail is critical if we are going to re-imagine and reinvent our own.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Tagged: A, B, C: Three Short Novels, Samuel R. Delany, science-fiction, The Ballad of Beta-2, The Jewels of Aptor