Book/Theater Interview: Library of America Celebrates Arthur Miller’s Centennial

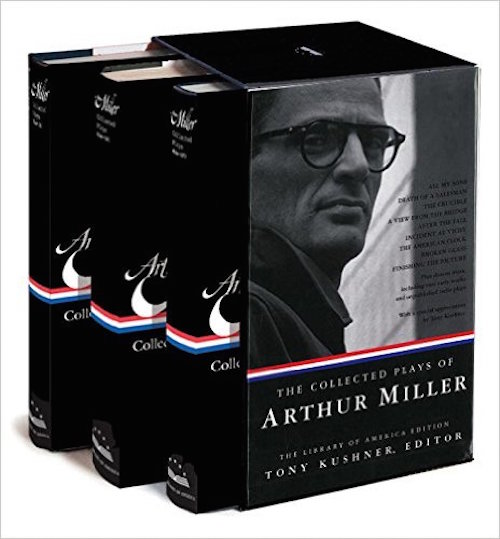

The Library of America has done its part to applaud Arthur Miller’s 100th birthday with a handsome three-volume set of his plays.

Playwright Arthur Miller.

By Bill Marx

Playwright Arthur Miller would have turned 100 this year (tomorrow, in fact), and the festivities in the Boston area have been…muted, to say the least. Miller’s work is embraced on the London stage (the Young Vic recently staged a powerhouse production of A View from the Bridge), but he is pretty much on the outs on Broadway, so that may have dampened the spirits for a party over at the Huntington Theatre Company and other local troupes. The dramatist didn’t write any musicals, so that pretty well pushes him out of the whoop-de-doo orbit of the current junta at the American Repertory Theater. When it comes to birthday huzzahs, there is an unfortunate sense among many, including some critics and producers, that Miller is an earnest scold, a nagging proponent of “liberal guilt.” It also doesn’t help that we are in a theatrical era of empowerment rather than tragedy. Intractable social problems just aren’t all that inspiring…or hummable.

Still, last month there was a well-received production of Broken Glass at the New Repertory Theatre, and tomorrow night, the Gloucester Stage Company is tossing The Arthur Miller Centennial, “a multimedia performance featuring recorded interviews with Miller himself, as well as scenes from some of his best-known works, including The Crucible, Death of a Salesman, and After the Fall.” The Library of America has done its part, publishing a handsome three-volume edition of Miller’s collected plays (Tony Kushner, editor). The warhorses are all here, but what’s most gratifying is to find some interesting unfamiliar plays, such as his final script, Finishing the Picture, which have not been produced in Boston. Perhaps an enterprising stage company will take a look at these possibilities, including the early drama The Grass Still Grows. Even at 100, Miller might have some surprises for us.

I asked Jim Petosa, the director of New Rep’s Broken Glass, to send along some questions to LOA about Miller, and added some of my own. The Editors at the LOA graciously responded.

Arts Fuse: Theater critic Harold Clurman admired the plays of Arthur Miller, noting the presence of “a certain clean, moralistic rationalism.” He went on to write that “it is not easy to make the rational a poetic attribute,” but Miller’s talent lies in “his ability to make his moral and rationalistic characteristics produce a kind of poetry.” It isn’t customary to see Miller as a poet. Looking at the breadth of his work, do you agree?

Editors of Library of America: All great art, written and otherwise, could be said to have a “kind of poetry” to it, and Miller’s plays are no exception. But forget “kind”: he’s widely recognized as the “master carpenter/builder” of the American stage (to borrow LOA editor Tony Kushner’s characterization), and that workmanship is evident in verbal choices in every line. At his best, Miller is a poet, not just like one.

AF: Miller was influenced by the dramas of Henrik Ibsen. Miller did an adaptation of An Enemy of the People and a number of his plays, including 1994’s Broken Glass, reflect Ibsen’s fearlessly diagnostic spirit. Will Miller’s plays remain as relevant as Ibsen’s? Or will his scripts date, as some critics charge?

LOA Editors: Some of Miller’s plays—Death of a Salesman, The Crucible—have become so central to the American repertory that frequent theatregoers may have seen them many times, and long for something new. As things stand in 2015 though, Miller, like Ibsen, seems as alive as he ever was—his plays, and not just Salesman and Crucible, are revived all the time, and not just out of duty or respect for the past but for the great performances they bring out of actors, and the intense reactions they still elicit from audiences.

AF: What does Miller’s final work, Finishing the Picture, tell us about his relationship to movies and popular culture? Do the early radio plays in the LOA set add anything to our understanding of his writing for the electronic media?

LOA Editors: Resurrection Blues (2002) is the play that first leaps to mind as an expression of Miller’s relationship to contemporary media culture; Finishing the Picture (2004), in many ways a late look back on his relationship with Marilyn Monroe, is more complexly personal. The former play is unusual though—it’s one of Miller’s rare attempts at satire. (An American “reality TV” crew arrives in a Banana Republic, hoping to film a love crucifixion; mayhem ensues.) If Resurrection Blues was Miller’s only play, you might imagine him to be deeply cynical about the media culture of his day. He surely was, to some degree; but he started his professional life writing for radio in the 1940s and wrote screenplays for television and film, too. When his screenplay Almost Everybody Wins—a 1984 crime thriller finally released in 1990 as Everybody Wins—ultimately failed at the box office, he allowed himself to express some frustration at the way Hollywood had treated his work, and a preference for the theatre. But anyone who reads Almost Everybody Wins can see he was in love with movies, too…

Library of America’s Boxed Set of the “Collected Plays of Arthur Miller.”

AF: Does Miller’s work critically address for contemporary audiences the rise of xenophobic thought in Europe and the USA?

LOA Editors: It’s hard to think of another significant American playwright—even another American writer—for whom xenophobia broadly considered loomed so large, and who addressed it so forcefully. Miller of course had the Holocaust and McCarthyism in mind, but surely The Crucible (1953), Incident at Vichy (1964), Playing for Time (1980), Broken Glass (1994)—these and several other plays will resonate with audiences witnessing new forms of xenophobia today.

AF: In the latter decades of his career Miller was more popular as a dramatist in Europe—particularly in London. Have American audiences and critics been ambivalent about Miller? And if so, why?

LOA Editors: Miller’s later plays met with both popular and critical acclaim in London and were barely seen in New York or elsewhere in the US. The main difference was not in the audiences so much as in the economic situation of the theatre in the two countries. Broadway, then as now, was almost entirely unsubsidized; plays had to turn a profit and pull in crowds on a certain scale—and having had a string of Broadway successes, New York looked to Miller to fill big houses in a way that his later works just aren’t really made to do. Anything less from him seemed to indicate “critical ambivalence” or even failure. He tried, perhaps, and failed to remain relevant for Broadway—but Broadway was in a kind of decline anyway. The West End proved a far more hospitable home for him in his later years, allowing him to experiment without huge financial pressures determining every choice. These late plays are one of the real “discoveries” for readers in the Library of America collector’s edition of Miller’s work: many may not have had a chance to see them performed, and they read magnificently.

AF: How did Miller’s work influence the plays of Tony Kushner, the editor of the LOA volumes? They are both political dramatists who write from a strong moral base—yet there are powerful differences as well as similarities.

LOA Editors: The last word on this should be Kushner’s own—his “Arthur Miller: An Appreciation,” originally delivered at a memorial service for Miller in 2005, is included as a pamphlet in the Library of America boxed set. His early encounters with Death of a Salesman, Incident at Vichy, and A View from the Bridge inspired and challenged him to become a playwright, he says there. Of course there are differences in tone and subject matter, but what Kushner says of Miller is also true of Kushner himself: one of his gifts is to see through “the grand scale horror” of historical events to the details of the inner lives of single human beings.

AF: Are there any literary surprises in the LOA volumes? Even for those who know Miller’s work well? And do you have any favorite, off-the-beaten-path Miller works?

LOA Editors: Even seasoned Miller fans are unlikely to know his two early plays The Grass Still Grows (1939) and The Half-Bridge (1942), published for the first time in an appendix to Collected Plays 1987–2004, the third volume of the Library of America edition; it’s fascinating to read them side-by-side. The earlier play is by far the more successful of the two—someone somewhere ought to produce it. It may not be “great” Miller, but taken for what it is, a modest domestic comedy, it’s vivid, sweet, genuinely heartwarming. You can imagine a lot of it may draw on Miller’s own upbringing; all of its minor details seem true to life. It’s an incredibly accomplished play for someone in his mid-20s, scarcely a false note in the whole thing. The Half-Bridge came later and works far less well; you could call it “flawed,” overplotted, overwrought, full of wooden dialogue, mixed genres, mixed messages, everything but the kitchen sink. But it’s a fascinating failure, and you can see much future Miller in it.

One literary surprise in Collected Plays 1964–1982, the second volume in the collection, is not a play but a short essay about acting, “To the Actors Performing this Play: On Style and Power.” Miller wrote it for the actors then rehearsing Incident at Vichy (1964); he was clearly frustrated, even angered, by the popularity of “The Method.” Maybe prompted by some actor’s question about his or her inner motivations, Miller responds with an extremely sharp short burst of ideas about what “acting” really means. He’s a terrific theorist, writing from the middle of an actual production.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007, he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: American-drama, Arthur Miller, Collected Plays Boxed Set, Editors of Library of America