Visual Arts Review: Photographer Rose Marasco — The Search for Juxtapositions

Rose Marasco’s strong sensibility is always at work, searching for contrasts to capture in her photos.

Rose Marasco: index, at the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, MA, through December 6.

Rose Marasco, “Projections No. 5,” 2007. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

By Kathleen C. Stone

Rose Marasco is a composer of images, and every photograph in the retrospective now up at the Portland Museum of Art bears her distinctive mark. Whether in her deliberate choice of subject, a montage of images or a scene she’s arranged, her presence is there.

Marasco likes juxtaposition, and that thread runs through much of her work. There’s a handsome early photo of a kitchen wall hung with cutting boards, colanders, and other utensils, the dark objects creating a syncopated rhythm against the white wall. In another, a black overhead door is mounted into a white garage. We know Marasco’s strong sensibility is at work, searching for contrasts to capture in her photos.

Beginning in the 1970s, Marasco’s work turned toward the local, after she moved to Maine and began teaching at the University of Southern Maine. In one small series, she finds her juxtaposition in Maine subject matter. Three photos show dark trees stark against light backgrounds – a fresh snowfall, a painted wall, and a misty, sunlight infused sky – all in the distinctly urban setting of Portland. The fourth, taken at Reid State Park, is an interior shot of the bath house where shower stalls, dark in shadow, are punctuated by a patch of sunlight on the floor. It’s a study in double juxtaposition – light and dark, urban and rural. Plus, there’s a twist – we expect a bucolic scene in the seaside park but instead we get plastic and concrete.

Rose Marasco, “Photomontage,” 1981−82. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Montages, with different photos in one frame, are a favorite of Marasco. At first, we think the montage is just one picture, but really there are multiples, cleverly put together. In one, for instance, we see a curving stretch of road with a one-hour parking sign in the middle. Only when we look closely do we realize the visual trick; the sign belongs with the roadway on the left and on the right is a divided highway that just happens to curve at the same angle.

All this perceptual play can become a little over intellectualized, even arid at times, but when Marasco turns her attention to the personal, things become much more interesting. Not that she’s putting her own life on display. She’s not, but she cannily mines the lives of other women for photos that shimmer with a variety of emotions.

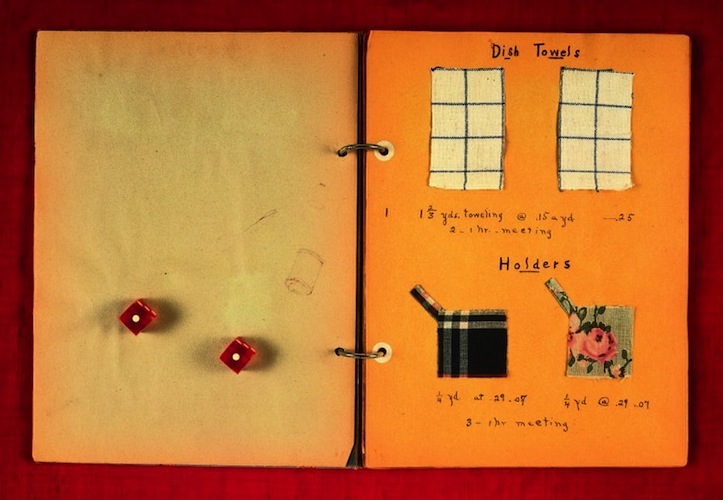

In one series, Dice Book, she composes scenes using a record book kept by a seamstress. With the pages spread, Marasco places two die on the left, the pips showing a different combination in each photo. Opposite is the seamstress’s archive of her work, including a sample of her client’s choice of fabric, the cost, and the amount of time spent on the project. We don’t know the date of the seamstress’s log but, judging from the fabric costs (fifteen cents a yard for toweling and twenty-nine cents for pot holder material), it must have been a long time ago, a time we barely recognize. Still, we are invited to imagine a dynamic connection between the two women and feel something of their lives.

Rose Marasco, “Dice Book,” 2000. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The emotional center of the show comes with another set of diaries, these culled from the Maine Women Writers Collective at the University of New England. Covering various years between 1873 and 1921, each is open to the second week of January where we get a glimpse of the women’s lives when Maine weather is cold and the scenery bleak. In Egg Diary, we read that Friday was a “busy and happy” day, when the author built a fire in the kitchen, baked beans, and a neighbor came to buy buttermilk and a peck of apples. On Saturday, another neighbor stopped by for eggs and the writer sold her “the only fresh one we had.” An egg sits atop the open pages, and we are free to contemplate what the single fresh egg meant to the woman who bought it and what it meant to the diarist who parted with it. In Oatmeal Diary, Marasco has sprinkled dry oatmeal over the pages where we read entries such as “Taking 3 tsp. oatmeal twice a day.” This is a mother’s journal, recording the minute details of her child’s intake and output. In Wishbone Diary, Marasco has placed a turkey wishbone, dried and ready to be pulled apart, above the open pages. We read the entry, “O Gee, I wish something would happen.” Across the generations, we feel a pang at the sign of yearning.

More recently, Marasco has composed scenes of lush color. In one striking example we see a corner of her dining room, warm with a black and white tile floor and lit fireplace. With two of her photos above the mantle and a Cindy Sherman poster on the wall, it’s Marasco’s wink at the master of self-contemplation from her own self-referential composition.

Kathleen C. Stone is a writer pursuing her MFA degree, a lawyer who earned her JD many years ago, and, even before that, was a student of art history. Her blog can be found here.

Tagged: Kathleen C. Stone, Photography, Portland Museum of Art, Rose Marasco