Jazz Commentary Series: Jazz and the Piano Concerto — Mavericks, 1938-1983

This post is part of a multi-part Arts Fuse series examining the traditions and realities of classical piano concertos influenced by jazz. The articles are bookended by Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts: the first features one of the first classical pieces directly influenced by jazz, Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World (February 19 – 21); the second has pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performing one of the core works in this repertoire, Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G (April 23 – 28). Steve Elman’s chronology of jazz-influenced piano concertos (JIPCs) can be found here. His essays on this topic are posted on his author page. Elman welcomes your comments and suggestions at steveelman@artsfuse.org.

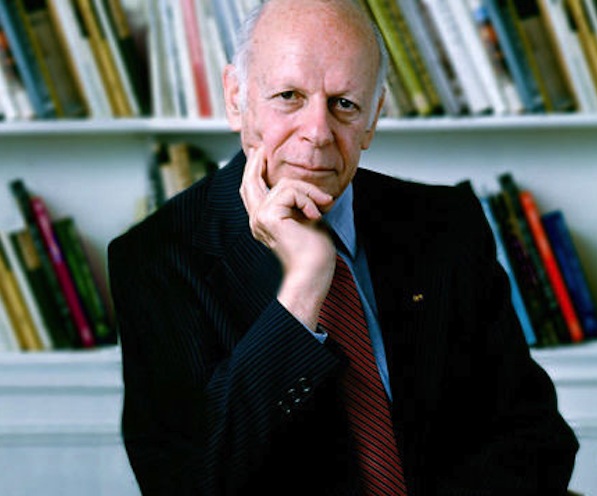

Benjamin Britten sitting at his piano, 1950. His wartime piano concerto uses jazz for sarcasm.

By Steve Elman

This post continues my look at composers who followed their own distinctive paths when they incorporated jazz into their piano concertos.

This second group of mavericks starts with two giants of the 1930s, and then we jump ahead to the ’60s, ’70, and ’80s, represented by one composer each. But time period is an illusion here. Each of these five composers stands outside of any school or stream.

With the first version of Benjamin Britten’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 13 (1938), the JIPC takes a huge step forward. Britten is the first classical composer of the top rank to incorporate jazz elements into a piano concerto since Ravel, and this concerto is recognized as one of the masterpieces of the mid-century. In the way Britten originally conceived of it, this work qualifies as one of the greatest of the jazz-influenced concertos, even if its jazz references are relatively few and confined to a single movement. For its premiere and seven years after, the concerto’s unusual third movement was entitled “Recitative and Aria,” which is where the jazz resides. In 1945, Britten replaced it with a jazz-free movement he called “Impromptu.” The reasons for this are not clear, but “Recitative and Aria” evokes Gershwin and some of the bad-boy attitude of George Antheil. Perhaps, given the wreckage of post-World War II Britain, the composer felt that this movement was no longer appropriate.

Space does not permit a full description of the work here, but all four of the original movements are considered by some analysts to be varying responses to the prospect of war: the first movement suggests a modern version of the storm in Beethoven’s “Pastoral” symphony, the third a sarcastic and brutal waltz, and the last a grimly determined march.

Since the third movement contains the jazz influences, I’ll concentrate my observations there. The movement begins with the “Recitative,” which is actually a series of conversational exchanges between solo voices from the winds and the piano. In general, the winds play it straight and the piano thumbs its nose at them, with a jazzy edge – or at least with a deliberate evocation of the irreverence of the ’20s. English horn has the first statement, picking up some of the tentative quality of the end of the second movement and trying to resolve it into a song. The piano arrives, with three notes that are first tentative, then bold, then resolved into a little twist that takes us right into Gershwin and the ’20s. A clarinet statement follows – not in the Rhapsody in Blue vein, but slightly bluesy nonetheless. The piano comment that follows is deliberate bad-boy music, not as bold as Antheil, but still pretty cheeky. Solo bassoon comes in with a distinct Stravinsky Rite of Spring feel. The piano passage that comes next is noirish and late-night. The stabbing chords in the left hand and a gentle rhythm would not need much of a nudge to slip into the mood of Gershwin’s slowest piano prelude. Solo flute is next, more French, less parodistic than the music before it. The piano replies with left-hand figures that are almost in the stride vein and then a right-hand melody continues the bad-boy attitude. With a few final notes, the piano becomes serious and ushers in a horn statement, very dark and Germanic, almost a call to battle. The piano slips into a waltz tempo, supplying some of the sarcasm of the second movement. A full orchestral passage sets the tone for the piano’s next comment – finally earnest — which leads to the Aria section, where the jazz is left behind. “Recitative and Aria” has been published as a stand-alone piece for piano and orchestra, but in my opinion it does not make sense except within its original context.

William Schuman –his wartime piano concerto uses jazz for drive and excitement.

William Schuman’s Concerto for Piano and [Small] Orchestra is a great American companion piece to the Britten concerto, composted at about the same time. It was revised, like Britten’s concerto, in the ’40s (but not before the end of World War II). There is no hint of an extra-musical program, but this does not make it any less profound than Britten’s work. What separates it from Britten’s and the concertos I discussed in my previous post is its confident and original use of a musical language that does not depend on the ’20s for its validity or meaning. Yes, there are influences of Gershwin and Copland, but these are nods to the past rather than foundations.

Schuman’s concerto is superbly written and beautifully structured. It is also woefully neglected, perhaps because the piano part requires a fiery virtuoso. In two of the three movements, he uses syncopation and rhythms associated with jazz to give the concerto drive and excitement. The opening of the first has an atonal Gershwin flavor which pops up again after a slower interlude in the middle of the movement. The third opens with strongly syncopated piano, almost an atonal novelty rag, and features a long cadenza that combines a bit of jazz rhythm with extensive counterpoint and a wistful look back at the contemplative Coplandesque mood of the second movement. The entire piece is a richly satisfying adventure.

Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin’s reputation as a maverick is secure. He feels free to combine diverse elements, sometimes whimsically, often for sarcastic effect. His Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 2 (1966) is no exception, an uncompromisingly modern work which contains a big jazz surprise in the last movement. The tempo in the outer movements never drops to the traditional pace of a “slow movement,” but the central movement is the fastest of the three, suggesting a reversal of the traditional fast-slow fast concerto structure.

Each movement of the piece is titled: “Dialogues,” “Improvisations,” and “Contrasts.” “Improvisations” is jazzy in the sense that there’s a kind of brashness and push to the music that might not have been there if jazz didn’t exist, and the conclusion has some of the bold flourishes of the Ravel concerto. But “Contrasts” makes this a true JIPC. At about three minutes into the movement, there is a sudden swing-band-like smear from the orchestra, and the piano jumps into the first of three quick passages accompanied by walking bass and traps; the second and third of these have vibraphone as well, and the third has a chordal passage that is a bit like Bill Evans’s piano solo in George Russell’s “All About Rosie,” though without Russell’s distinctive harmonic grounding. These quick moments of real jazz feeling throw a retrospective streaks of irony across the whole work.

In 1976, for the American bicentennial, William Bolcom delivered his Concerto for Piano and Large Orchestra. He described it as simultaneously a bitter reaction to the patriotic celebrations and a “wry commentary” on Gershwin’s Concerto in F, “particularly in its episodic form.” Both statements are well-realized by the music. There are few specifically jazz elements, but all three movements provide moments of what might be called “twisted Gershwin.” The first also includes some touches of ragtime, a form Bolcom knows intimately — in this movement, he recalls its romantic and slow-drag side. It also includes a bit of what Peter Dickinson, in his notes to the Hyperion recording, calls “stride tempo.” The third movement was infamous in its time for its Ivesian pastiche of patriotic songs, turn-of-the-(20th) century parlor tunes, traditional Americana, and show music. It’s a great pile of jokes, with something elegiac, even sinister, lurking beneath the riot. Such a strongly sarcastic and time-tied piece runs the risk of becoming anachonistic. Now that the century has turned, it may have to wait for 2076 to find its relevance again – even though Marc-Andre Hamelin made a very convincing recording of it in 2000.

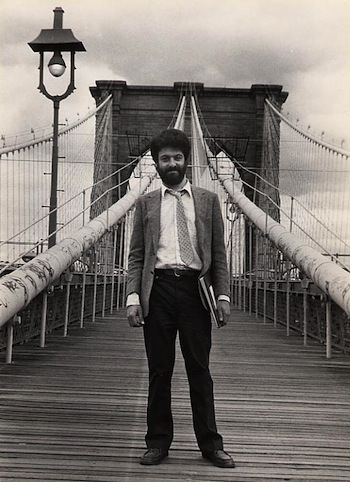

Tobias Picker on the Brooklyn Bridge, 1983.He comments on Gershwin and the twenties in his concerto celebrating the Brooklyn Bridge.

Tobias Picker’s Keys to the City [for Piano and Orchestra] (1983), also known as his Piano Concerto No. 2, is another brilliant piece of music that has yet to find a regular place in the concert hall. It unfolds in a single movement (there are clear divisions into fast-slow-fast sections), and makes use of significant jazz influences, which are refracted distinctively through a very personal prism. It was commissioned for the 100th anniversary of the completion of the Brooklyn Bridge, but Picker recalls and comments on the music of the ’20s rather than that of the 1880s.

Gershwin is inevitably part of the mix, but other jazz moods are suggested throughout — they are finally made explicit in the closing section. At about twelve and half minutes in, a flourish from piano and orchestra ushers in walking bass in the brass, along with syncopation and a boogie-ish solo piano passage. This rhythm continues (basses doubling the left-hand piano figures) as the orchestra comes in to contribute some of the most idiomatic ’20s orchestration in the piece, punctuated by a couple of saxophone breaks. There is much more to enjoy, including a parody of Gershwin in a false ending.

More: To help you explore compositions mentioned above as easily as possible, my full chronology of JIPCs contains detailed information on recordings of these works, including CDs, Spotify access, and YouTube links.

Next in the Jazz and Piano Concerto Series — Mavericks, 1960-2004

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Tagged: Benjamin Britten, JIPC, Jazz, Piano Concerto, Tobias Picker, William Bolcom, jazz-influenced piano concerto