Book Review: The Life of Lou Reed — Those With No Moral Compass Beware

We learn, over and over, that the author of the song “Vicious” dispensed his legendary acts of cruelty with sadistic aplomb.

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story by Victor Bockris. HarperCollins, 560 pp, $15.99.

Lou Reed: The Last Interviews and Other Conversations, Melville House Publishing, 128 pp, $12.75.

1971, Sherborn, MA.

Two freshmen from a Catholic high school after school in a suburban bedroom. On the tinny stereo one kid puts on The Velvet Underground’s harrowing 12-minute song “The Gift,” a record he borrowed from his older brother

When it’s over, the kid visiting asks “can you play that again?”

1978, Framingham State College, Framingham, MA

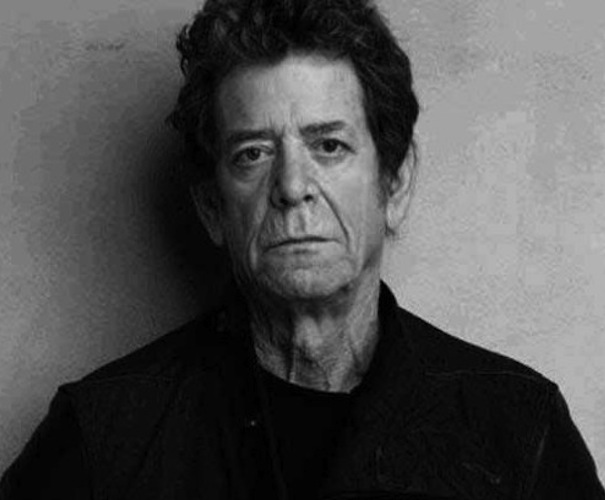

Lou Reed in a black t-shirt, tight denim jeans and mirror-shades shielding him from the glare of the spotlights, facing a rapt crowd of onlookers in a campus auditorium. A thin but muscular Lou Reed gazes out, the epitome of urban cool, and announces….

“Who said this is some bullshit college nobody ever heard of or gives a shit about, and that we wouldn’t play here?” And with that he turns to the band, counts off two-three-four, and starts into “Sweet Jane.”

1984, Orpheum Theater, Boston, MA

A single pin spotlight illuminates Reed onstage, as he wraps around his forearm a length of cord, pumps his fist, then appears to plunge a hypodermic needle into his arm. The band breaks into “Heroin;” the crowd’s roar of approval is deafening.

By Tim Barry

For those of us whose lives were saved by rock ‘n’ roll, the importance of Lou Reed cannot be overstated. But who was Lou Reed, other than a face on an album cover and a distinctive drawl? Now that he’s been gone a couple of years, what do we know about him, truth rather than myth? Tentative answers are beginning to appear.

It’s fairly well accepted now in art history that we can only truly see Caravaggio through the works of artists who were influenced by him. Dutch scholar Mieke Bal coined this approach “preposterous history,” which seems a handy way to view the career of Lou Reed.

Indie-rock bands cottoned-on to the stylistic dregs of Reed’s Velvet Underground on the heels of its early-1970s demise.

Soon bands like The Modern Lovers, Roxy Music, The Only Ones, and later The Feelies and The Violent Femmes were trafficking in the stripped-down sound propelled by understated but insistent guitar-lines and primitive, minimalist drumming. And Reed’s monotone vocal drawl and matter-of-fact delivery is still echoed in the work of The White Stripes, The Strokes, and many others.

In Victor Bockris’ compelling account of Reed’s life and career in Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story we follow him from his time as a suburban depressive in the Long Island of the ’50s to cover-band geek with a guitar at Syracuse University. We look on as he founds the Velvet Underground, generating it out of the gutter grandeur of downtown New York. Andy Warhol produces their first album. They become anti-rock icons.

If the outlines of Reed’s career are familiar to fans of ’60s and ’70s rock, there is plenty here to satisfy even the hard-core Reedite. His solo career, the druggy period post-Velvets, when Reed sought mainstream success yet also recorded the meant-to-be-unlistenable Metal Machine Music, a full-length lp of feedback and dissonance, is examined here in close-up.

And while the interviews with his musical collaborators, record executives, journalists, and friends are instructive, it’s the People Magazine-type reports that turn out to be most eye-opening: Lou on his farm in New Jersey in the ’90s, shooting hoops but no longer shooting dope. Lou collecting motorcycles and guitars. Lou and his third wife, the avant-rock conceptual artist Laurie Anderson, decorating their apartment together in the West Village.

Rocker Lou Reed — he raised acting-out and behaving badly in public to an art form.

Bockris was an insider, a pal of Warhol and an intimate of William S. Burroughs, and he brings to the narrative such breezy, catch-and-catch-can readability that you can (sort of) forgive the biography’s ample journalistic shortcomings.

For example, in his skimpy account of Reed final days, the biographer gives just three short sentences to the liver transplant. Really? In light of his self-inflicted organ damage, was it justified that Reed could cut to the head of the transplant waiting-line? But we don’t learn how the organ was obtained. Was some doctor a Velvets fan? And where are the interviews with, say, hospital personnel, or others who were around him in his final days. Was Reed able to shelve his customary hauteur when he was staring death in the face?

At times roadies are mentioned, and they blurt out a line here and there. But shouldn’t there be….more? Of course, whether Reed deserves a truly in-depth, no-stone-unturned biography is an open question; this book, a revised and updated edition of Bockris’ 1995 Lou Reed bio, is an entertaining read but it is more like a ‘notes toward a biography’ than a comprehensive treatment, ala James R. Knowlson’s life of Samuel Beckett, Damned to Fame, or Peter Guralnick’s comprehensive study of Elvis Presley, Last Train To Memphis.

We do learn, over and over, that the author of the song “Vicious” dispensed his legendary acts of cruelty with sadistic aplomb. How he tortured his collaborator, the singer Nico, when she was in the throes of amphetamine withdrawal, by dangling the drugs before her eyes but denying her a share.

Granted, this makes for compelling reading. Bockris is present at William Burroughs’ apartment one night when Reed comes to meet the great writer, the ‘other’ avatar of junk. Reed walks in and snarls “Is there a chair for me, or do you want me to sit on the floor?” He then viciously insults Burroughs again and again. The seen-it-all Burroughs, a courtly gent with old-school manners, accepts it all with a chuckle.

Like Keith Moon, James Brown, and Keith Richards, who raised acting-out and behaving badly in public to an art form, Reed felt compelled to play the rebellious-to-the-max role of Lou Reed. Which accounts for his nasty arrogance.

This ‘living a life as an ongoing performance’ is a thread running through the fascinating interviews in Lou Reed: The Last Interviews and Other Conversations. The lead-off dialogue pits gonzo scribe Lester Bangs, drunk, against a sullen yet game Lou Reed. Holed up in a wee-hours New York hotel room after a show, they parry and thrust to a virtual draw.

Bangs’ odd and poetic reportage makes for vivid reading as he brings a strung-out Reed into sharp focus: “….Lou’s sallow skin almost as whitish as his hair, whole face and frame so transcendently emaciated that he had indeed become insectival. His eyes were rusty, like two copper coins lying in desert sands under the sun all day with telephone wires humming overhead….”

The slender 114 pages of this collection contains a number of precious ‘copper coins’: slightly different facets of Reed’s sensibility emerge through each interrogation. For example, Neil Gaiman and Paul Auster put Reed in a calm and retrospective frame of mind, perhaps because of his respect for their writing.

But it’s the professional rock journalists like Rolling Stone’s David Fricke who ferret out some astonishing revelations: Fricke: “Did Andy (Warhol) give you subjects to write about?” Reed: “Sure, he said ‘Why don’t you write a song called ‘Vicious?’ And I said ‘Well, Andy, what kind of vicious?’ ‘Oh, you know, vicious, like I hit you with a flower.’ And I wrote it down, literally.”

We learn that in 2008 Spin Magazine popped the $64,000 question, “Do you think your music has been something of a guide for people to learn about behavior they might not otherwise encounter?” Reed stares and remains silent, then offers “Maybe they should sticker my albums and say ‘Stay away if you have no moral compass.’”

Tim Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, Hyannis, and Provincetown, and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, in Provincetown.