Theater Review: “Albatross” — A Return to Theater as Poetry

Albatross is terrific — a powerful script, vital performance, and imaginative stage design.

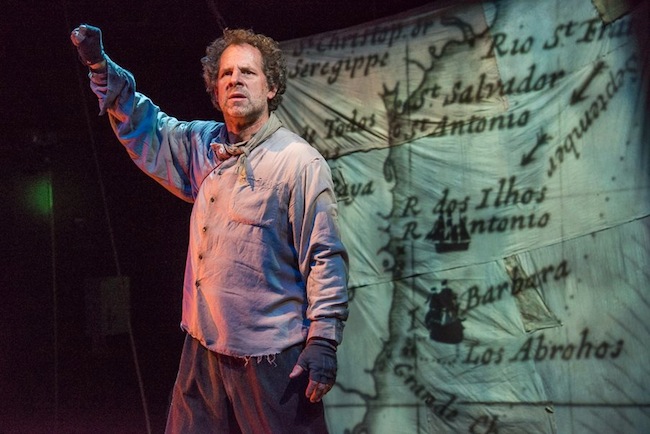

Benjamin Evett in The Poets’ Theatre production of “Albatross.” Photo: Andrew Brilliant/Brilliant Pictures.

By Ian Thal

Albatross by Matthew Spangler and Benjamin Evett. Directed by Rick Lombardo. Presented by The Poets’ Theatre at the Jackie Libergott Black Box at the Emerson Paramount Center, Boston, MA, through March 1.

[The production is being revived by the New Repertory Theatre in the Charles Mosesian Theater at the Arsenal Center for the Arts, 321 Arsenal Street, Watertown, MA, May 21 through 24.]

Dressed in a tattered, thread-bare coat, trudging past coils of rope and carrying a flashlight, a man drags a trunk onto the stage. He adjusts the lights and begins to gesticulate like a jester, launching into a ribald story in Italian grammalot. After a while he realizes he is not being understood. He borrows an iPhone and, using the GPS feature, determines that he’s in Boston and adopts his native tongue, a particularly vulgar dialect from southwest England.

As he unfurls patchwork sails, running ropes through pulley blocks and tying them around cleats, he introduces himself as the ancient mariner of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s narrative poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner. It may be a curse or a blessing, but he still lives, centuries after the publication of Lyrical Ballads. Much as he did outside the wedding in Bristol, he has been wandering the world, working on ships in both war time and peace time, telling his story to all who will listen. Over time he has become an autodidact, contemptuous of what passes for higher education amongst the affluent bourgeois of today, scornful of the the literary theory that passes for scintillating dinner conversation amongst the college educated. His knowledge is that of the poetry and myths the cognoscenti no longer learn as well as the lives of people that history rarely records.

There was a time when familiarity with this great poem could be assumed; it was a staple of high school, often parodied by students. (My twelfth-grade English teacher reports that he still teaches Coleridge to his seniors.) If your memory is hazy, it is easily downloadable. Though the mariner freely quotes stanzas from The Rime, particularly in the third act, which hews closely to Coleridge’s original, Albatross is about as original a work as can be and still be considered an adaptation. The mariner is insistent on telling his story his way, noting that the poet had left much out of the published piece.

Our post-modern situation — digital access to an amazing amount of information, even some familiarity with various approaches to cultural interpretation, but superficial knowledge of the literary canon — is one of the themes in Albatross‘s that Coleridge could not have anticipated in 1797 when he put quill to paper.

The mariner begins his story in 1720 in Bristol, describing the everyday squalor of the city: The streets are filled with refuse of all kinds, including rotting animal carcasses, disease is rampant (the mariner’s own child is dying), and any able-bodied male, especially if he has had any seafaring experience, must be wary of anyone offering him a pint. Chances are good that it will be drugged with opium — and he will regain consciousness in a ship’s hold.

After one drink too many, the mariner awakes to find himself the navigator of a ship captained by a notorious privateer known only as Black Dog. The bandit has received permission from the crown to hunt Spanish ships off the coast of South America. Named for his mouth of canine teeth, Black Dog is notorious for how much he relishes chomping down on the flesh of Spaniards, be they sailors or inquisitors. The mariner may fear the pirate’s enthusiasm for grotesque punishments (such as tying a dead albatross around the mariner’s neck), but he also enjoys, centuries later, playing the role of his deceased captain. Also on board is Roger the Dodger, the mariner’s poshly accented and obsequious cousin, who has joined the crew out guilt; he is to blame for getting the mariner involved in this unsavory business.

The decision of Spangler and Evett to place Coleridge’s sea yarn in the context of privateering in the aftermath of War of the Quadruple Alliance against Spain grounds the original poem’s romantic mysticism in an atmosphere of violent possibility in uncharted waters, while the often lugubrious lives of the sailors, both on deck and in port, dramatizes the frailty of the human body. Indeed, the mariner often takes brusque issue with Coleridge’s idealism, as when he comments on the oft-quoted quatrain:

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

Water would not stay potable on a long sea voyage, the mariner explains, so sailors drank rum – and if that ran out, only the sailors’ own urine was left. (Perhaps the poet suspected that such realism would likely have kept Rime of the Ancient Mariner unpublishable — it certainly would have kept it out of the high school curriculum.)

Benjamin Evett in The Poets’ Theatre production of “Albatross.” Photo: Andrew Brilliant/Brilliant Pictures.

The collaboration between Evett (Producing Artistic Director for The Poets’ Theatre) and Spangler (a California-based playwright best known for adapting literary works to the stage – most famously his adaptation of Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner) has produced a strikingly dramatic text, one that demands the power and versatility of an actor of Evett’s calibre. Leaving aside his impressive vocal performance (no dialect coach is listed in the playbill), Evett’s physical dexterity is dazzling. He effortlessly shifts from the bawdy clowning of the Italian jester to miming the agonizing strains of a seaman’s labors. He dramatizes the disorientation of the dehydrated sailor’s body going into shock as well as the soul-deadening despair of seeing the ship’s crew perish.

The production’s design elements and storytelling are nimbly integrated. Cristina Todesco’s set design is ingenious in its simplicity: Garrett Herzig’s projections play across three sails pulled taut with ropes and pulleys. Stephanie Brownell’s patchwork construction of the sails nicely breaks up the pristine flatness and right angles of standard digital screens. Herzig’s animations, whether they are glimpses of churning Antarctic waters or visions of the disoriented perspective of the mariner, support every dramatic turn in the story. Director Rick Lombardo not only performs sage alchemy with these visual elements, but has come up with a compelling sound design: there’s the claustrophobic drunken chatter of a Bristol pub, the monotonous rocking swishes of a ship cruising across calm and uncharted waters, and the mysterious bumps and knocks in the seas of a spirit world where the mariner’s compatriots meet their fates.

The Poets’ Theatre, which was founded in 1950, has returned after a hiatus of many years. The organization insists that it will take up its original mission: to bring theater back to its ancient roots in poetry and storytelling. Albatross makes good on this exciting promise. With so much new play writing inspired by (some would argue obsessed with) film and television, a dedication to drama as exhilarating language rather than eye-popping spectacle, sexy acrobats, or monosyllabic dithering is not just welcome, but downright necessary. (Bill Marx of the Arts Fuse discusses The Poets’ Theatre’s history with Artistic Director Robert Scanlan here). This auspicious premiere production of The Poets’ Theatre’s reinaugural season is compact enough to tour, which means Albatross can set sail and spread its lyrical word to other stages — Bon Voyage.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. Two of his short plays appeared in theater festivals this past summer. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled From The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: Benjamin Evett, Matthew Spangler, Robert Scanlan, S.T. Coleridge, The Poets' Theatre

Boston audiences will get another opportunity to see this show at New Repertory Theatre in Watertown, on May 21-24.

[…] to the Arts Fuse review of the premiere of this production earlier in the season, this one-man show, featuring a […]