Classical CD Review: Seattle Opera’s Earthbound “Der Ring des Nibelungen” (Avie Records)

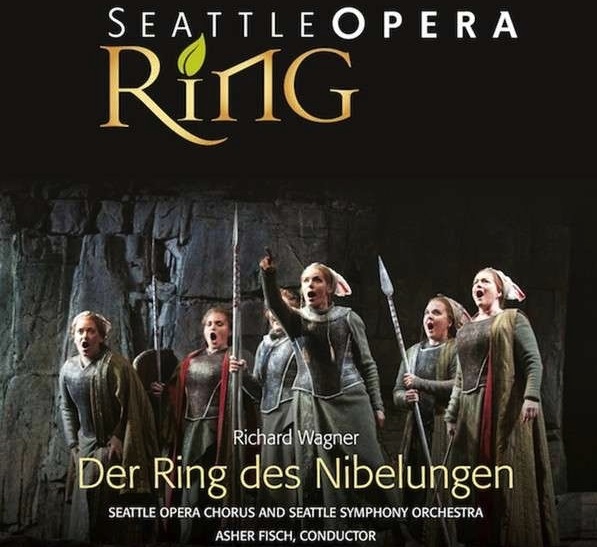

What one really wishes is that the Seattle Opera’s Ring Cycle had been released as a DVD, so that the compelling staging could be a part of the listening experience.

Der Ring des Nibelungen, Wagner. Seattle Opera, 14-CD box set, digital download, and for online streaming from Avie Records. $150.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

There is no shortage of Ring Cycles already on the market, including a dozen or so live accounts. So what does Seattle Opera’s recent release of their acclaimed “green Ring” (so called because of the focus on nature and the environment that is at the core of the production) add to the mix? In musical terms, it turns out, not so much. Yes, the orchestra plays strongly. Conductor Asher Fisch keeps everything moving along tautly and intelligently. But the singing, especially in key roles, often comes up short. And, when the competition in Ring Cycles includes the likes of Keilberth’s, Böhm’s, Krauss’s, Solti’s, Karajan’s, Boulez’s, Barenboim’s, and Thielemann’s and their attendant excellent casts, that’s a big problem.

In many ways the highlight of this set is that orchestra (made up primarily of members of the Seattle Symphony) that, despite patches of sour intonation, turns in a performance that never fails to impress with its energy and color. Balances are sometimes problematic – the low brass tend to swamp everything, including the full string section playing fortissimo, at big climaxes – but these seem less matters of conducting oversights or bad interpretative decisions than the results of imperfect microphone placement and the vagaries of recording live performances. Throughout these four operas, Fisch demonstrates not only a good sense of tempos, but also a strong understanding of how Wagnerian melody needs to be paced in order to unfold naturally and forcefully.

On the plus side vocally, the most remarkable contribution to this Ring is probably Stephanie Blythe’s magnificent Fricka. One doesn’t usually invest in fourteen hours of opera for this minor role, but, if the exception were ever to be made, it could excusably be done for this performance. Blythe’s Fricka is steely and by no means a pushover, but the warmth of her voice and approach to the role goes a long way to making this most shrewish of characters not just sympathetic, but human. Her second act scene in Die Walküre with Greer Grimsley’s Wotan is, arguably, the single best scene in this Ring.

Also strong are Stuart Skelton’s Siegmund and Mary Jane Wray’s Sieglinde, who, together, bring some great sparks to the first two acts of Die Walküre. Another bold highlight is Dennis Peterson’s Mime, who’s got both the tonal quality and musical personality needed to make this duplicitous character truly multidimensional. Mark Showalter’s Loge is strongly sung, if a bit less shifty than might be ideal, while Richard Paul Fink’s Alberich starts off unremarkably before really growing sinister by the middle of Das Rheingold; his returns in Siegfried and Götterdämmerung are most welcome. And Wendy Bryn Harmer brings a warm, vulnerable tone to Gutrune, certainly one of the Cycle’s most sympathetic characters.

Grimsley makes for a sturdy Wotan/Wanderer. His voice lacks some of the gravitas of Hans Hotter’s or James Morris’s, and for beauty of sound doesn’t trump John Tomlinson’s or Bryn Terfel’s. But it’s strong and commanding, nonetheless, and, especially in the second half of Das Rheingold and the latter acts of Die Walküre, delivers some truly compelling singing.

The other roles in Seattle’s production seem either miscast or to be filled by singers having a series of off nights.

Alwyn Mellor’s Brünnhilde stands at the head of these disappointments. In her defense, Mellor was sick enough to have to withdraw from performances of Siegfried and Götterdämmerung during this run, so her performances in these operas may not have been given at full strength. Still, one wonders why her cover Lori Phillips’s well-regarded accounts of Brünnhilde then weren’t substituted for those two operas. As things stand, Mellor delivers a competent, if never quite incandescent, Walküre and a promising wake-up scene in Siegfried. As the final act of Siegfried continues, though, her performance grows weaker. She has little projection in her low register; the high notes sound forced (the less said about her last note in the opera, the better. Suffice it to say, it’s mighty ugly); and her diction becomes increasingly unintelligible. Mellor’s appearances in Götterdämmerung are at times more adequate, but never fully shake off the sense of struggling to carry the part. Her account of the famous Immolation Scene may not be the least exciting on record, but it certainly doesn’t come anywhere near the most captivating. It’s hard to tell if all of these shortcomings are primarily illness-induced or an accurate reflection of Mellor’s vocal abilities and limitations. At the very least, her Brünnhilde here lacks the clarion brilliance of Birgit Nilsson’s, the commanding presence of Anne Evans’s, and the fresh warmth of Helga Dernesch’s or Deborah Voigt’s.

Also disappointing is Stefan Vinke’s Siegfried. Vinke’s at his best in the most intense sections, whether sparring with Mime, the Wanderer, or Fafner, and, occasionally, with Brünnhilde. In them, the energy of these dialogues (and occasional arias) causes him to shift into a voice that limits the wide vibrato and stuffy tone that makes his Siegfried sound both far older and less focused than he should. But, when he’s not appearing in these high-energy scenes (and sometimes when he is), that latter voice often takes over. And, considering the long stretches of monologue and introspection that make up parts of the Cycle’s last two operas, this results in an ultimately disappointing Siegfried and a frustrating Götterdämmerung.

Among other roles, one can possibly bear Daniel Sumegi’s Fafner, even if one can’t understand any of what he’s singing in Siegfried, but his Hagen, with its wobbly vibrato and fuzzy tone, is exasperating. Ditto for his Hunding. Lucille Beer’s Erda is matronly to the extreme and warbles not a little, that latter characteristic also shared a bit too much with Jennifer Zetlan’s Waldvogel.

The smaller ensembles leave something to be desired, too: the Valkyries tend towards shrillness and the Rhein Maidens make (and leave) little impression. Only the Norns in Götterdämmerung are strong, and that’s in large part because Blythe and Wray sing two of the three parts. The choral singing in that opera is also generally good, if not always convincingly Germanic in its diction.

Having said all of this, Seattle’s isn’t a terrible Ring Cycle. It just isn’t a particularly compelling one. There is quality singing to be found, even if it is not always consistent and if, with a couple of exceptions, none of it challenges the best that’s already out there. What’s most lacking throughout Seattle’s Ring is the sense of mystery and sheer excitement this epic demands. Most of the sung performances are simply too literal and earthbound. The ones that stand out – Blythe’s, Skelton’s, Wray’s, and Peterson’s, especially – hold their own with at least the better ones already on disc. The rest don’t. In many ways, that’s simply a testament to the challenges of casting a Ring Cycle in a period when there isn’t a glut of clear-cut, great Wagner singers on the scene; then again, there’s never exactly been an overabundance of such voices.

What one really wishes is that this Ring Cycle had been released as a DVD, so that the compelling staging could be a part of the listening experience. (To judge from the pictures in the liner notes, it’s a beautiful, powerful visual production.) Alas, that’s not the case. What we have here is certainly a remarkable testament to the vision of Seattle general manager Speight Jenkins and the not inconsiderable ambitions of his opera company. For that they ought to be commended. That, vocally, theirs isn’t one of the more satisfying recent live Rings and that these performances, as a whole, don’t live up to the hype surrounding them is unfortunate. But, as H. L. Mencken once observed, one does what one can.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

It is Speight Jenkins.

I attended these performances and the sets are spectacular! I would love to have a DVD. I have not bought the CD’s since I would have little use for them – not speaking German.

Bob Connor

Houston, Texas

fixed … thanks ..