Visual Arts Review: The Young Have Come Down With “Warhol Mania”

In 1957, Women’s Wear Daily called Andy Warhol “the Leonardo da Vinci of the shoe trade”; the transformation of soup cans and Brillo boxes into fine art works doesn’t seem so surprising.

Warhol Mania: A Brand New Look At His Advertising Posters and Magazine Illustrations, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal, Canada, through March 15, 2015

By Tim Barry

If there’s anything left to be discovered about Andy Warhol, there’s a man in Canada who was put on earth to find it. Paul Marechal is an art-scholar and independent curator who is devoting a good part of his life to ferreting out the minutia, the ephemeral, the seldom-seen in Warhol’s body of work, and bringing it out into the light.

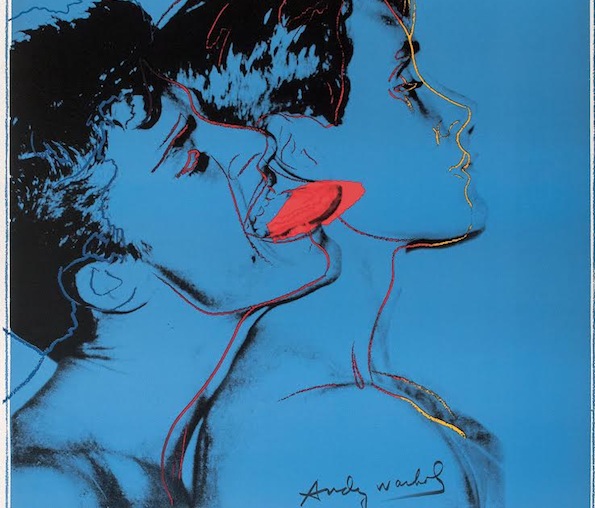

For many of us devotees of the white-wigged palatine of Pop Art, the spidery lines of the late ’50s shoe-drawings are great to see, but hardly a revelation. And while it’s nice to be reminded that Warhol designed the famous zipper-cover for the Rolling Stones 1971 “Sticky Fingers” album, is a showing of his graphic designs–work that really wasn’t meant to be ‘art,’ per se–fodder for a museum exhibition?

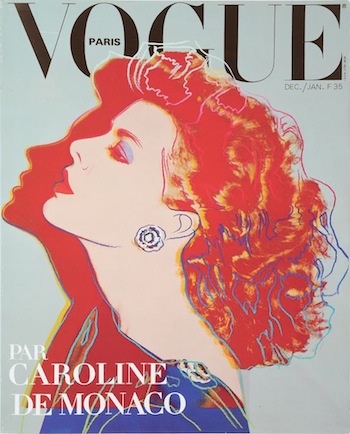

The answer is yes, why not, and it also serves to address a pesky question: what constitutes an artwork anyway? Because what you have in this Montreal show is several rooms full of handsomely framed magazine covers, off-Broadway lobby-cards, book dust-jackets, and posters advertising shows of Warhol’s ‘actual’ art. There’s no original art in the show.

Which seemed a problem at first blush. One had hoped for a look at some of the drawings. Maybe some sketchbooks. Anything that betrayed the hand of the artist. But that’s not what this show is about.

And it’s really not what Warhol was about.

At the heart of Warhol’s aesthetic, at the core of his philosophy — indeed what may be his most lasting contribution to artistic practice in our millennium — is the very absence of the hand of the artist. In a white-hot period of production from the ’60s through the ’80s, Warhol and his minions at The Factory cranked out thousands of indelible images. But though he made hundreds of paintings and thousands of prints and drawings, most of what he gave to the world was delegated to other hands.

So in 2014 we have other factories. We have Damien Hirst in London marshalling a phalanx of art-school drones on his spin-paintings. Jeff Koons keeping a small regiment of New Yorkers busy fabricating things in ceramic, mylar, and steel. And from Tokyo there’s Takashi Murakami taking this to a level Warhol would have loved, with everything from t-shirts to key-chains for sale, alongside solo shows at Gagosian.

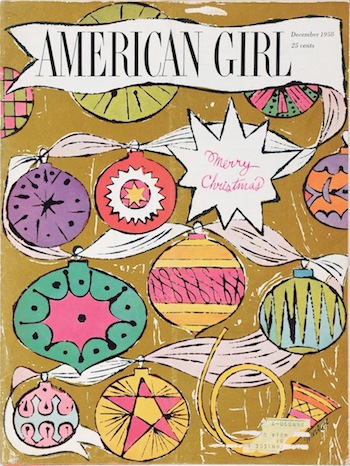

An early Warhol magazine cover

You could argue that Warhol was merely part of a long tradition. Leonardo and Raphael had assistants who contributed brushstrokes and filled in areas of canvas. Rubens’s murals and decorations for Philip IV’s hunting lodge near Madrid were executed by assistants according to the artist’s designs.

Nevertheless, the happy result of Andy’s collaborative art-making is his output. His job from ’70s on mainly involved saying “a little more blue right there…no, I want a French-butter yellow here, not a Dijon-mustard yellow….” We now have a lot of Warhols to consider.

Warhol’s staggering work-ethic was probably derived from his peasant-stock origins in depression-era Pittsburgh. Arriving in New York around 1948 he labored in advertising and window-dressing at Bonwit-Teller. He cold-called record companies pleading to do album-covers. His drawing-hand was rarely idle, churning out illustrations for anyone from Film Culture Magazine to Schrafft’s Restaurants.

His first ‘exhibition’ in New York was at a restaurant called Serendipity 3, where the owners were charmed by the curious lad from the provinces, so they offered him some wall-space. And it was a success–original Warhol drawings sold well at $2 to $50.

Warhol made an early jump into fine art; in 1956 Curator of Prints William S. Lieberman included him in the “Recent Drawings U.S.A.” exhibition at MOMA. But Andy always kept one foot in the world of commercial art. Right up to his 1987 demise, he married business with his social schedule. If he was having dinner at Nan Kempner’s he was on the lookout to book commissions for portraits. When he moved in the world of Jaggers, Kissingers, and Kennedys, he was always lining up photo-shoots, which were later turned into prints for sale. As Andy famously said, “someone has to bring home the bacon.”

Paradoxically, both the scarcity and familiarity of the exhibition’s images serve the show well. Curator Marechal has culled together fifty-year old magazine covers, posters of which only a few survive, and other paper oddments. There are Playboy and Time magazine covers: Diana Ross, Debbie Harry, and Michael Jackson all frozen in time for our examination.

In an email, Marechal notes that “the standard biographies, such as Bockris and Bourdon, mention that Warhol worked for ‘7 or 8 different magazines,’ I ended up with 63 different magazine titles.”

This project relates as much to the antiques and collectibles milieu as it does to ‘fine art.’ This seems solidly Warholian; on an early trip to see Europe’s art treasures, Andy would rotely utter ‘great’ and ‘wow’ in front of a Michelangelo. But if he was wandering down by NYU, and somebody was selling ’40s vintage Statler Hilton silverware off of a blanket–that would really quicken his pulse.

So the love of the common, the celebration of the pedestrian article, was always at the heart of the Warhol worldview. When you discover that in 1957 Women’s Wear Daily called him “the Leonardo da Vinci of the shoe trade,” then the transformation of soup cans and Brillo boxes into fine art works doesn’t seem such a quantum leap.

Tellingly, Warhol is one of the few artists of yesteryear that still fascinates youth culture. He has morphed from art-historical figure into Andy, The Brand. Of course, he’d have loved this. Of the over 800 people in attendance at the opening of this exhibition, a solid chunk were in skinny-jeans, nose-rings, and under 25.

If there’s any hope for the future of the visual arts as vital, contemporary entertainment it is in keeping this demographic interested. Maybe Warhol’s final legacy will be getting young people through the doors of art museums, where they might discover what else is there.

Tim Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, Hyannis, and Provincetown, and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, in Provincetown.

Tagged: Andy-Warhol, Magazine covers, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, movie posters