Book Review: Associate Justice Antonin Scalia — A Judge Who Refuses to Evolve

Bruce Allen Murphy conveys the impression that Scalia knows how he feels on every issue before the briefs have been argued, then pulls out citations of law which justify his pre-conceived notions.

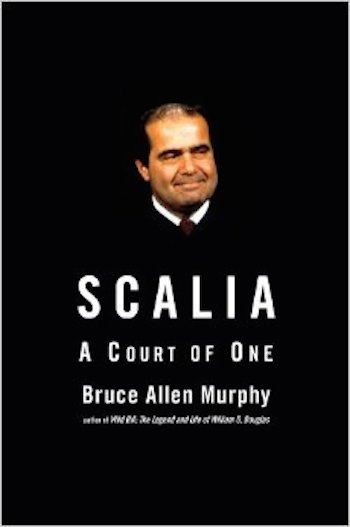

Scalia: A Court of One, by Bruce Allen Murphy. Simon and Schuster, 644 pages, $35.00.

By Thomas Filbin

“He’s a complicated man, but no one understands him but his woman.” — Isaac Hayes, theme from the motion picture Shaft.

If ever there was a man who is defined by, indeed trapped in, his culture, religion, temperament, and upbringing, it is Antonin Scalia, Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court since 1986. Most people change or evolve at least a little in a lifetime, but to Scalia the very word “evolve” has the connotation of betraying principle in favor of a squishy relativism of the moment. People who have allegiance to truth do not evolve, they stay as they are and fight to their last breath against all those whose views deviate from certain absolute notions of the good and the right. So thinks the man who feels the Constitution is not a living document to be applied to changing times, but one writ in stone whose purpose is to prevent change.

Bruce Allen Murphy, author of previous biographies of Justices Abe Fortas and William Douglas, has written a thorough and scrupulously researched account of the life of a man considered the most contentious, stubborn, and acerbic ideologue ever to sit on the court, and those are just things his friends would say about him. Although appointed by Reagan as a conservative, Scalia one by one alienated all of his natural allies on the court who were moderate to conservative Republicans. He has attacked O’Connor and Kennedy in particular even when he concurred with their decisions, making sure in his written opinions to hector them that they had missed some point of law or came to the right decision for the wrong reasons. One gets the feeling that little Nino was told by his fourth grade teacher that he was the smartest little boy who had ever come to P.S. 13 in Queens and he never got over it.

Born to Italian immigrant parents, he learned respect for learning and hard work from his father who, through Herculean determination, learned English well enough to receive a doctorate from Columbia. Antonin was educated by the Jesuits at Xavier High School in Manhattan, where the classics were taught accompanied by military style discipline. An honors student, he thought of Princeton but felt snubbed there in an interview because of his ethnicity, and instead went to Georgetown where he was an outstanding scholar and prize debater. The art of debate for him, however, was so competitive that it meant not merely winning on points, but hammering his opponents into the ground. This trait might be useful for a trial lawyer, but appellate judges are supposed to possess a reflective nature, hearing all the arguments and weighing them against one another before deciding. Murphy conveys the impression that Scalia knows how he feels on every issue before the briefs have been argued, then pulls out citations of law which justify his pre-conceived notions.

Scalia’s career was a steady ascent from brilliant law student at Harvard, to working lawyer, professor and writer, government official and counsellor, appeals court judge, and finally to the Supreme Court. He knew which avenues best secured promotion, and he caught the eye of his masters as one who could be trusted to exercise judicial restraint. His views leave little role for the highest court, instead favoring what state legislatures or the democratic process determine to be the state of things. The unabridged will of the people and their elected lawmakers trumps the notion of majority rule with respect for minority rights in this judge’s mind.

One of Scalia’s guiding lights is a principle of constitutional analysis which he described as “originalism” in the beginning, but which morphed into a more arcane version called “textualism”. Originalism seeks to discern what the founding fathers intended when they wrote the Constitution, while textualism asks what the ordinary person at that time understood the words of the Constitution to mean. Scalia takes this so seriously that he has written a lengthy treatise on the subject, but more so and more ridiculously when he cites things such as Webster’s 1828 edition of the dictionary. One can imagine eyes rolling in chambers as the other justices listen to his declamations on all things from voting rights, gun laws, health care, and same sex marriage. If it wasn’t conceivable in 1789, it isn’t permissible today seems to be his mantra.

The book spends a goodly amount of time on Scalia’s extra-judicial speechmaking. Judges must be circumspect in their public comments lest they are thought to be players rather than referees. A devout and conservative Catholic (certainly more Catholic than the current pope), he lectures frequently at Catholic colleges and law schools, often citing the evil of religion being banished from the public square by a wall of separation he feels the founders never intended. The father of nine children and an ardent admirer of St. Thomas More, who lost his head as Henry VIII’s chancellor for not assenting to the king’s divorce and break from Rome, Scalia sees himself similarly as a martyr of sorts for his beliefs. (Thomas More had earlier in his career put some heretics to death, making you half imagine the justice’s heart is there as well). His critics have suggested Scalia’s religion influences his judgments, although he denies it, but he accepts no general constitutional right of privacy under which the court struck down state laws criminalizing homosexual acts. He opposes abortion and same sex marriage, and indeed has compared societal disapprobation of homosexuality as similar to disapproving of murder, polygamy, or cruelty to animals. When called to account for it by a gay law student at a lecture, Scalia denied it was a case of similars, but rather a reductio ad absurdum, which the student should have known. Denigrating the opponent as well as disagreeing is the Nino style.

Despite Scalia’s claim of a judicial philosophy, he has never let it get in the way of his inherent beliefs and loyalties. Murphy writes that in overturning a long existing precedent in a Second Amendment case it was not a “…problem for Scalia, who was by now adept in manipulating his originalist theory to reach the result he sought.” In Bush v. Gore, Scalia assumed an aggressive stance to convince his fellows to take the case on appeal from Florida, and to find in favor of stopping the vote count to guaranty Bush the presidency. This was a low moment in SCOTUS history as Justice Stevens noted: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

Scalia feels that textualism is the one true way to interpret the Constitution, all others being merely theories held by judges. Once again, the true faith doesn’t need to be proven. Most scholars, whether lawyers, historians, or literary critics would say his textualism is just another theory, and not a very good one, flawed like the pedantic Rev. Casaubon’s magnum opus, The Key to All Mythologies, in Middlemarch. The Constitution for Scalia is static by intent, stating: “It certainly cannot be said that a constitution naturally suggests changeability; to the contrary, its whole purpose is to prevent change…”

Justice Scalia. Perhaps Ruth Bader Ginsberg believes that inside the bully boy is some better soul who, but for chance, could have been other than he is.

Murphy rightly notes that most justices regardless of party are philosophically pragmatist, considering the consequences of their decisions. How will this affect people in their dealings, they ask; what outcomes will ensue? Roberts, Kennedy, and Souter are all of this stripe: judges believing decisions need to function in the world of affairs. Scalia in this, like all things, begs to differ.

One term the court has used in recent decades to overturn or modify decisions of bygone eras is to invoke the notion of “…the evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society…”, as Justice Kennedy wrote for a 5-4 majority in the 2005 case of Roper v. Simmons, holding the execution of a person under eighteen to be unconstitutional as cruel and unusual punishment. The section of the Constitution which prohibits such punishments, but nowhere defines what they might be, underscores the weakness of Scalia’s view. Capital punishment for minors, whipping, and cutting off ears were all punishments which existed in colonial times, and which the founding fathers were familiar with, but in not clearly stating what is cruel or unusual specifically, leads to the inescapable conclusion that this was meant to be left up to future judges to determine.

Scalia approaches age eighty in good health, determined to soldier on. Once he had hopes of converting the court to his views, perhaps even becoming chief justice, but as that ship has sailed he can only go on as he has. There is a trait called judicial temperament; less brilliant people have been better judges because they possessed it. His only friend on the court is Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who shares his love for opera. One imagines the tiny, frail, but steel spined Ginsburg undisturbed by Scalia’s outbursts. Perhaps she believes that inside the bully boy is some better soul who, but for chance, could have been other than he is.

Murphy observes in summing up that “…Scalia will continue to use his originalism and textualism decision making theories, his traditionalism as dictated by his religious beliefs, and his partisan conservatism, not always seeing how these are, at times, contradictory.” This well written biography leaves us believing that Scalia will be remembered as an idiosyncratic footnote and a long serving anachronism who saw the law as an immutable object, not as a force whose purpose is the advancement of civilization and the protection of the individual.

Thomas Filbin is a lawyer and freelance writer. His reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Sunday Globe, and The Hudson Review.

Tagged: Antonin Scalia, Bruce Allen Murphy, Scalia: A Court of One, Supreme Court