Book Review: Joni Mitchell — One Side, Now

The pleasures of Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words are the pleasures of being a fly on the wall.

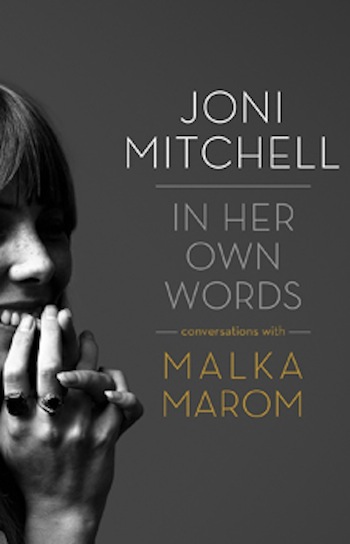

Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words by Malka Marom, ECW Press, 292 pp., $29.95

by Debra Cash

There’s a wonderful moment in Nicole Holofcener’s savvy adult rom-com Enough Said when Marianne (Catherine Keener), an inexplicably affluent poet whose Santa Monica home is decorated with Wegner wishbone chairs, explains to her insecure masseuse (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) that Joni Mitchell really liked the galleys to her upcoming book. It’s a perfect sink-the-knife comment, aimed at an entire generation of women who haven’t quite fulfilled their creative aspirations. The next best thing to being Joni Mitchell, the princess of Laurel Canyon, it seems, would be to be counted her friend.

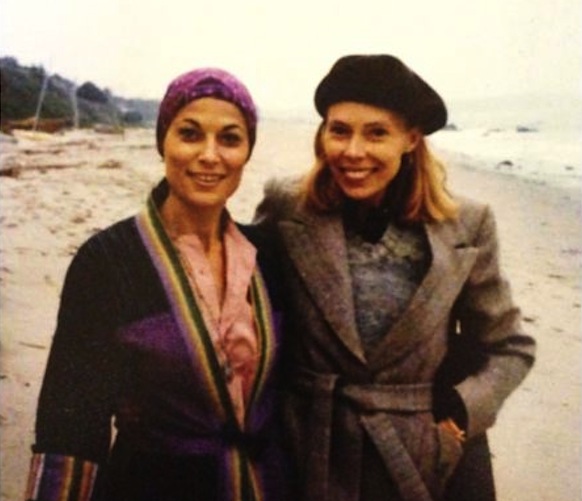

Malka Marom has been Joni Mitchell’s friend since 1966. Back in the day, Marom was wearing a dark beehive hairdo and singing in 14 languages as half of the folk act Malka & Joso (Spralja). The couple ultimately hit their career highpoint with a CBC show in a slot that followed the televised Saturday night hockey game. In Canada, this was a big deal.

As far as Joni Mitchell’s career goes, Marom claims a little (thwarted) credit for being present at the creation. The day after she first heard Mitchell in a tiny Toronto coffeehouse, she writes in Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words, she phoned the A&R guy at her record company to rave about the talented newcomer. He’d never heard of her, and, when he deigned to come to the club, he left in the middle of her set. She had, he said, no stage presence. At the time, even Mitchell herself would probably have agreed. He would have become a richer man, though, if he had closed his eyes and just listened.

During the course of their 40-year friendship, Marom conducted and audiotaped three long interviews. The first was a five day session in 1973, recorded just before the release of Court and Spark. That interview — deleting the off-the-record details like Mitchell’s feelings about giving her baby girl up for adoption — became the basis of a CBC radio broadcast. She followed it up with another series of interviews in 1979, just before the release of Mitchell’s controversial collaboration with Charles Mingus, who had just died of ALS. The final extended interview that makes up this book was conducted in 2012, as Mitchell faced her 70th birthday and the women exchanged impressions of health, aging, and the thorny issue of creative legacy.

Mitchell’s biographical trajectory is well known to anyone who has been privy to what she once called “the star making machinery behind the popular song”: the Canadian girlhood in Alberta and Saskatchewan, where her parents were a teacher and a grocer; polio at 8 (rocker Neil Young contracted the disease during the same 1951 epidemic); the poverty of the early busking and folkclub years; her illegitimate pregnancy and longing for the child she has struggled to befriend in adulthood; the bad first marriage and tabloid-ready romances (Graham Nash, James Taylor, Warren Beatty, Larry Klein — she was pissed when Rolling Stone did a graphic illustrating the chain of broken hearts); her chain smoking, which has essentially destroyed her singing voice; and her continuing devotion to painting in a style that has loosened and opened into abstraction along with the drift of her lyrics.

Many of the folk/rock legends of the ’60s and ’70s have been offering up public reminiscences in recent years. In the final interview of the book, Mitchell is amused by the ideas that she and her friends are becoming historical figures. It’s not hard to find her comments on her life and career in interviews coinciding with retrospectives and award ceremonies (there’s a particularly lively one conducted by Jian Ghomeshi), the release of tribute albums such as Herbie Hancock’s Grammy-winning River: The Joni Letters, and in media like the documentary portrait Joni Mitchell — Woman of Heart and Mind: A Life Story which ran on public television.

The pleasures of Joni Mitchell: In Her Own Words are the pleasures of being a fly on the wall. The volume is framed as being made up of relaxed, girlfriend-to-girlfriend conversations with occasional insights from others in Mitchell’s entourage. Marom asks about the singer/songwriter’s creative process, sometimes bringing out photos and mementoes or previous quotes to jog Mitchell’s memory, other times just fawning. The conversations go back and forth in time, but there’s a rough chronology. As expected, Mitchell describes her process as a combination of the brainy and the intuitive. It’s hard to disentangle the strands.

It’s Mitchell’s middle years — the years after Both Sides Now and Blue (and what she calls at one point “the Nordic angst thing”) that are the most interesting. Her prior commitments to exploring unfamiliar tunings and unresolved chords helped her edge into jazz’s unconventional territory, as did learning to overdub. She’s self-aware about her own non-technique in Hejira:

Somebody said it was like I was improvising around a melody that only I knew. And in a way, it was true because it was influenced by sax players who were riffing on a melody which isn’t there, but it’s a standard — you know, “Stardust,” even though they’re playing around it and they’re not using the syllabication of the lyrics. They’re playing thirty-second notes, if they want to, or sixteenth notes, I was trying to write like that with the liberty of a jazz horn player.

She is also honest about the crazy-making of mass adulation (something compressed in the song “For the Roses”) and how “the performer threatened the writer.” She worries about becoming a mere tunesmith (she takes a nasty swipe at Bob Dylan). She resents it when her genius is not recognized — by the marketplace, I guess, since her fans remain legion — and chalks it up to American music being as homogenized as Velveeta. But in the 1973 interview she also said that “at a certain point, I knew it was a dog race, so I thought ‘Why do I want to be part of a dog race? If I want to be in this race, I’m gonna be the rabbit.'”

Joni Mitchell will be 71 this November, and she hasn’t had an easy few years. She was diagnosed with a rare — and some say psychosomatic — condition called Morgellons, in which she says she feels like there is barbed wire under her skin. It makes it impossible for her to wear clothes for long periods of time or leave the homes she has in a remote area of British Columbia and in Bel Air.

Illness, however, doesn’t account for the snide comments, the bitterness, the grudges she seems to keep for decades and more. Nor does it account for the way she takes credit for a number of things ranging from the introduction of self-publishing as a songwriter to the closing of the last of the Irish Magdalene laundries. She even claims to have started the craze for gold medallions among rap stars based on an unfathomable blackface costume she pulled together for a Hollywood Halloween party.

On the cover of Turbulent Indigo she portrayed herself as Vincent Van Gogh sans ear, and in the course of Marom’s interviews she compares herself to Mary Cassatt and Picasso. She mentions that her whole catalog is dying (really?), and adds “For a while Beethoven had a similar problem.” Gosh, couldn’t she just settle for Gershwin?

Love her music or not, Joni Mitchell’s a compelling story. Just don’t expect her to read your galleys.

Debra Cash has reported, taught and lectured on dance, performing arts, design and cultural policy for print, broadcast and internet media. She regularly presents pre-concert talks, writes program notes and moderates events sponsored by World Music/CRASHarts and cultural venues throughout New England. A former Boston Globe and WBUR dance critic, she is a two-time winner of the Creative Arts Award for poetry from the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute and will return to the 2014 Bates Dance Festival as Scholar in Residence.

© 2014 Debra Cash