Book Review: Samuel Beckett’s “Echo’s Bones” — Anticipation of Masterpieces to Come

Echo’s Bones is a fascinating immersion, somewhat inept in its means, but sincere and gravely serious, in a subject that Samuel Beckett made increasingly his own.

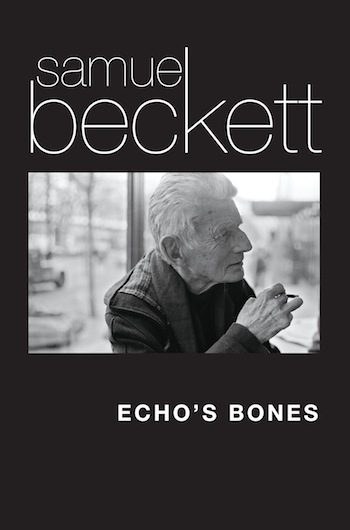

Echo’s Bones by Samuel Beckett. Grove Press, 121 pages, $22.

By Robert Scanlan

A previously unpublished short story Samuel Beckett wrote in 1933, when he was 27 years old, is coming into print eighty-one years after it was written and rejected for publication. This fact alone opens the thorny question of what to do with Samuel Beckett’s residuae, for there is more “Beckett” floating about in unpublished autographs and typescripts than there is published Beckett in print. Beckett wrote assiduously every day, and a vast majority of his daily exploratory scriptae led nowhere. Yet he destroyed very little of his brouillons (as they are called in French) — quite the opposite: he saved fragmentary drafts assiduously and stored boxes and boxes of these writings with friends. Vast amounts still remain in private hands, vast amounts were turned over to Jim Knowlson, Beckett’s official biographer, and are now safely stored (I presume) in the Beckett archives at Reading University. Should the exuviae and disjecta (as Beckett himself called them) be added to the published canon? If so (as here), at what cost to Beckett’s stature and reputation?

The question is one I have been embroiled in before, when the founder of Grove Press, Barney Rosset, in 1994 defied everyone and went ahead with plans to publish Beckett’s first completed play, Eleuthéria, in an English translation. Although Beckett and his wife, Suzanne Déchevaux-Dumesnil, had, indeed, pedalled the typescript of Eleuthéria (along with that of En attendant Godot) to theatre directors and producers in Paris in the early 1950s (they were strapped for cash), Beckett swiftly suppressed Eleuthéria when Godot found its audience and made him famous. Rosset ended up (no one knows quite how) with a copy of Eleuthéria, which — in need of cash himself in the early ’90s — he claimed was sent to him by Beckett for publication. “Why else would Sam have sent it to me?” Rosset protested, when efforts were made to block his publication of the retracted play 5 years after Beckett’s death.

Rosset prevailed by defying threatened lawsuits — something he had made a lifelong habit of doing, and as habits go, it proved an aggressively successful one. His publication of Eleutheria in an English translation by Michael Brodsky forced Beckett’s French publisher, Jérôme Lindon, to publish the play in its original French. But Lindon was bitter and angry about it. He told me he was deeply offended by the crossing of a line Beckett had drawn, explicitly. Lindon and Beckett were very close, and Lindon, as the chosen literary executor, felt he knew better than Rosset what Beckett would have wanted. Rosset’s argument was circumstantial: he was Beckett’s American publisher, and he had possession of a copy of the typescript. That settled it.

At my last meeting with Beckett, a few months before his death, Beckett said wearily to me “It will be impossible to control it,” and I understood him to be letting me, and others (especially his nephew, Edward, who now governs the estate) off the hook a bit about policing his work after his death as strictly as he himself had done while alive. My first real test was over Eleuthéria, and many of us “Becketeers” remain of two minds about the play’s published existence. I sided with Lindon at the time. Edward Beckett has steadfastly resisted any and all requests to stage the play. When he relents, I hope I get the honor of directing the premiere. I have strong ideas about how to do it. How’s that for ambivalence?

Thus, when I was asked to review this Grove Press publication of Echo’s Bones, I suddenly had a terrible sense of returning to a queasy subject, a tar baby of a topic: what to do with the vast remaining unpublished papers of Beckett. Yet I can see that a strong argument can be mounted for publishing Echo’s Bones, and that argument has obviously prevailed. Beckett worked hard at the story and submitted it for publication. He was disconsolate when it was rejected. This is firmly attested in the record. But as Eoin O’Brien (who also knew Beckett well) has recently pointed out in a letter to the Irish Times, Beckett passed up several earlier opportunities to include the rejected story in several re-issues of the short story collection More Pricks Than Kicks, in particular Rosset’s 1972 Grove Press edition. That Grove Press venture was Rosset’s cashing in on Beckett’s Nobel Prize, three years after the award.

Echo’s Bones was written, on request from the publisher, to round out (some would say, to pad out) the collection of ten short stories Chatto and Windus was about to publish under the title More Pricks Than Kicks. This publication in 1934 was an important landmark in Beckett’s early career. Charles Prentice, editor of the press, was kind and supportive in his handling of the young author, whose collection of stories was obviously provoked as a response to Joyce’s Dubliners. A detailed narrative of how Echo’s Bones came to be written and submitted — after the other ten stories had already been accepted as a stand-alone manuscript — is told admirably in Mark Nixon’s long introduction and an appendix in this new volume. It should be pointed out that of the 121 pages of this new volume only 48 are taken up by Beckett’s short story. Seventy-three pages are devoted to explanatory context, and they are superb examples of scholarly thoroughness. Nixon’s textual notes alone take up more pages than does the Beckett. They are indispensable for reading with full understanding Beckett’s ridiculously dense and allusive neophyte prose.

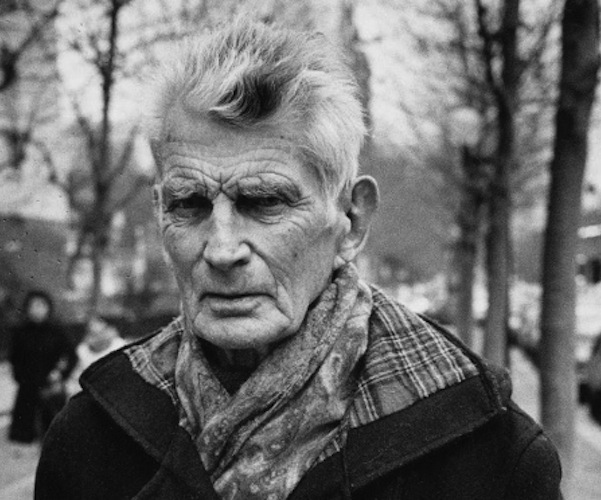

Samuel Beckett — this new book is not a good introduction to his works. The jacket should say, “If you have not read Beckett before, start elsewhere!”

I come finally (and reluctantly) to an evaluation of the story: one’s ostensible reason for purchasing the volume. The story is grotesque and bizarre, unpleasant and doggedly rebarbative. It is not a straightforward pleasure to read, by any standards, and its confused and disorienting aesthetics might be considered an embarrassment to Beckett’s reputation. The great Beckett scholar Ruby Cohn — herself very close to Beckett for more than thirty years — had given me access to the story in the mid-1980s, and my single reading of her photocopy then left me puzzled and non-plussed. It struck me then as what it was understood to be then: detritus. Since re-reading it several times now, with much more attention (and my own increasingly mature understanding of Beckett), I find it of utmost interest for the detailed study of Beckett’s early development. This deep interest in Beckett, the young man, is clearly the orientation of Nixon, and all the scholars and editors he credits in preparing the present volume.

But is that enough for recommending this disturbing story to a contemporary public? It runs the risk — especially if one is unfamiliar with Beckett’s masterpieces — of making new readers dislike Beckett, and misjudge his genius. These are ample reasons for regretting the decision to publish. But it must be said, in fairness, that Nixon’s loving attention to explicitation at every turn stands as the best part of the book. Informative, thoroughly researched, sympathetic and everywhere intelligent, the critical apparatus serves as an antidote to the story itself, which Charles Prentice, who rejected it out of hand in 1933, was right in calling “a nightmare.”

Brief overview of the story itself: the title refers to Ovid’s tale of Narcissus and Echo. Upon her death, Echo’s body gradually disappears until all that is left of her is her repeating voice (still with us today) and a vestigial residue of bones that have turned into a small handful of stones. Beckett’s story takes place after its protagonist’s death, a character who died two stories earlier in the collection, More Pricks Than Kicks — for which this eleventh story, requested late by the publisher, is — in Beckett’s words — “a fag piece.” Beckett’s writing impulse was clearly spent when he returned to his dead protagonist, Belacqua Shuah, to comply with Prentice’s request to flesh out the volume. But he stubbornly brings back a corpse, or a revenant, and frames his final effort as a triptych: three encounters, one with a lubricious whore named Zaborovna Privet; a second with an impotent giant named Lord Gall of Wormwood (a Fisher King?) who asks Belacqua to sleep with his wife in order to engender an heir (the effort fails by producing a useless daughter, who cannot inherit); and a final gravedigger’s scene in which a cemetery groundsman named Mick Doyle exhumes Belacqua’s grave as the expired ghost watches from atop the tombstone. Only a handful of stones are found in the opened casket.

There is nothing very pleasant about the arcane prose or the märchen-like fantasmagorical scenes and characters, let alone the sardonically sordid sex. It smacks of an ennervated will doing its best to mimic the work of the imagination. But let me offer another pathway to (perhaps) appreciating this horror show of a story a little better. I have grown over the years to recognize just how horrible a year 1933 was in Beckett’s life. It was a year that wounded him irreparably, one that mangled his sense of himself in the world. The grim events of 1933 — I increasingly believe — marked and determined all his pain-wracked work throughout the rest of his life.

Two terrible events took place in the spring and early summer of Beckett’s 27th year: the death, in the month after his birthday, of his beloved cousin (and lover) Peggy Sinclair and the death of his father, Bill Beckett, just weeks later, a few days after the summer solstice. Jim Knowlson (in the Beckett biography, Damned to Fame) has established the fact that Beckett had a passionate semi-illicit love affair with Peggy, and that her sudden death (from tuberculosis) shook him deeply. It caused a wound that wouldn’t heal. While still in shock from Peggy’s death, Beckett had the horrible experience of witnessing his father’s heart attack, which at first did not kill him, but severely incapacitated this vigorous and beloved man. Beckett was home at the time, and assiduously nursed his ailing father, shaving him, and tending to his needs. He was in agony. After ministering to Bill for several weeks (imagine the hopes and fears!) Bill’s doctor called one fine day in late June, when Bill felt suddenly better and had a good breakfast, and pronounced that things were looking up. But a second and catastrophic heart attack killed Bill Beckett later that same day, and Sam was there, a helpless eyewitness to this second, and violent, “visitation of Thanatos.” Beckett’s 27th birthday was in April. Peggy died far away in Germany in May. Bill’s death took up the month of June. Echo’s Bones was written in October of that terrible year, less than four months after Bill’s interment, in a cemetery by the sea.

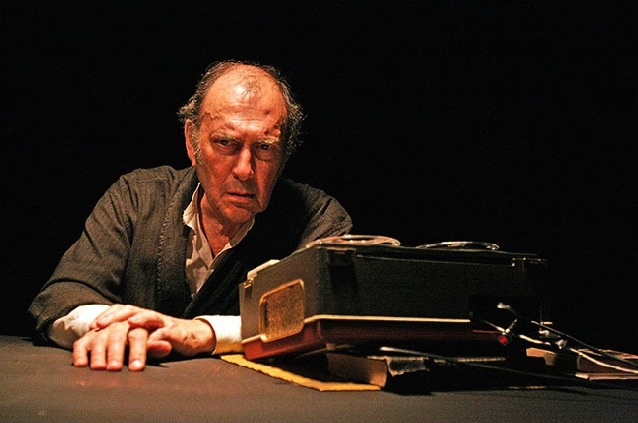

These terrible events precipitated Beckett into the worst years of his life. His personal losses re-appear, carefully coded, in many of his much-later mature works. Krapp’s Last Tape, for instance, very specifically points back from the 69-year-old man we see onstage (K69) to a K39, who, in the anniversary tape he records then, refers to having listened to a tape made by K27, who reported his father’s death that year. This is a biographical cryptogram. I similarly traced back the intricate web of time-references in the play named simply Theatre II, which features a disconsolate man on the verge of committing suicide on the feast day of Our Lady of Mercy (an ironic day to contemplate suicide), which happens to be the 12th anniversary of Bill Beckett’s death. The play re-enacts a close shave with suicide on this recurring anniversary of unabated grief and loss. In the light of undiminishing grief (a phenomenon, I think, that dogged Beckett to the end) an attentive reading of Echo’s Bones, written when the psychic napalm of death-consciousness was still intensely burning, becomes a gripping and revealing experience. Especially the desperate digging into a grave by the sea, reminiscent explicitly of the gravedigger’s scene in Hamlet, but clearly reconstructing Beckett’s obsession with his father’s new grave, also by the sea. It is an unforgettable expression of grief, and an agonizing grapple with what cannot (and would never) stay interred.

That final tableau of Echo’s Bones, the third panel of the disjointed triptych, takes on redeeming significance (it is my favorite part of the story) as a shattered young man’s desperate imaginative struggle with the awful reality of his father’s death. Echo’s Bones is thus a fascinating immersion, somewhat inept in its means, but sincere and gravely serious, in a subject that Beckett made increasingly his own. As a piece of strenuous writing, Echo’s Bones is, much before the fact, analogous to the tortuous process of reactive writing that produced Endgame two decades later, after Beckett witnessed and assisted during his brother Frank’s painful and protracted cancer death. Endgame has a fair claim to being Beckett’s greatest single work. That analogy alone is a redeeming argument for having published Echo’s Bones.

Still, this new book is not a good introduction to the works of Samuel Beckett. The jacket should say, “If you have not read Beckett before, start elsewhere!” With Waiting for Godot, for instance, and the ensuing 18 masterpieces for the stage; or with the much longer “mature” prose works that won Beckett the Nobel Prize, Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable. “Do not start here.”

Robert Scanlan has taught at Harvard for 25 years. He is reviving the Poets’ Theatre, having recently been re-elected President of the Board, and appointed Artistic Director. His book Principles of Dramaturgy is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

“The psychic napalm of death-consciousness” is really good. It is hard to survive the death of a parent when the world is such a cold place.

Thank God for art.