Classical CD Reviews: John Adams’ “City Noir” and Saxophone Concerto (Nonesuch) and Howard Hersh’s “Angels and Watermarks”

Howard Hersh, like John Adams, hails from northern California, and, as in the latter’s “City Noir,” the music on Hersh’s new album, “Angels and Watermarks,” embraces polyglot West Coast culture in various ways.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

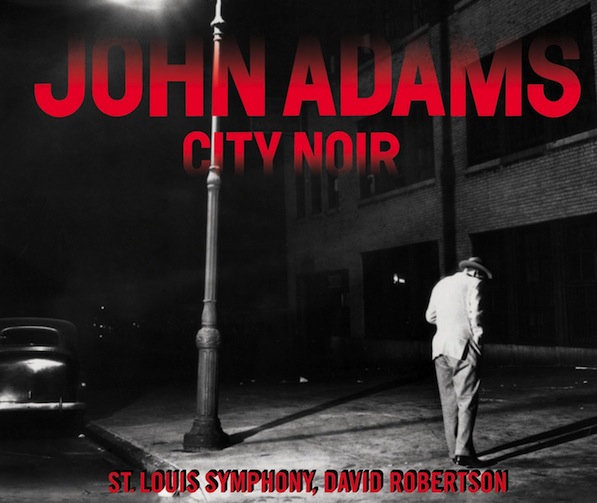

2014 is shaping up to be a good year for John Adams fans: in March, Deutsche Grammophon released the premiere recording of his acclaimed Passion oratorio, The Gospel According to the Other Mary, and this month Nonesuch brings out a new disc containing his three-movement tone poem/symphony City Noir and last year’s Saxophone Concerto. Sometime later this year, the San Francisco Symphony is scheduled to unveil the debut recording of 2012’s Absolute Jest. Heady days these are, indeed.

Adams wrote City Noir for the Los Angeles Philharmonic and its then-brand new music director, Gustavo Dudamel, in 2009. Drawing on the influence of Kevin Starr’s California-themed “dream” books and the heritage of film noir scores, it’s the third in a series of California-specific works Adams has written since 1991 (the underrated El Dorado and mesmeric The Dharma at Big Sur are the other ones). City Noir’s premiere, broadcast on PBS and released by Deutsche Grammophon, is a thrilling document, bristling with energy, edgy, and, unsurprising considering the momentous nature of the event, a bit nervous.

This new recording, with David Robertson at the helm of the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (SLSO), has all those qualities, too, but minus the opening night jitters. The performance is no less athletic than the L.A. Philharmonic’s, but this one can (and does) relax. It breathes. And, as a result, all of the music’s strange characters are more vividly etched.

Robertson draws an impressive degree of textural clarity from the orchestra. Adams’ dense, swirling writing throughout the first movement is as lucid as you’ll ever hear it, but it’s also charged with electricity. Robertson digs into the songful quality of the writing in this score: on more than one occasion, I was struck by the similarities between the opening movement of City Noir and that of Adams’ great, 30-year-old Harmonielehre. There are huge stylistic differences between the pieces, to be sure, but they share a similar lyrical sensibility.

That lyrical voice carries over into the second movement, titled “The Song is for You,” which features lengthy solos for saxophone and trombone. In the finale, Adams transforms a hazy, mysterious opening into a weird, wild, romping dance: it’s an essay in extroversion and the grotesque that, far from being off-putting, exerts an irresistible pull. Robertson and the SLSO play the daylights out of it, reveling in the music’s mix of raucous energy and high spirits.

In many ways, though, the main feature of this album is 2013’s Saxophone Concerto. Adams wrote it for Timothy McAllister (who also plays the acrobatic solos in City Noir) and, in his words, consciously aimed for an “American” sound, loose and gritty (as opposed to the more traditional “French” style, smoother with a fast vibrato).

“American” this concerto may be in its energy and brash outlook, but it’s also surprisingly “French” (at least in the late-19th/early-20th-century manner): Adams – who’s always been a master orchestrator – made use of a fascinatingly delicate palette of instrumental combinations in this piece, which gives the concerto, more often than not, a soft, glowing warmth, especially in the big opening movement.

If you’ve followed Adams’ music for any of the last twenty years, you’ll know that he tends to work with motives rather than tunes, and the Saxophone Concerto continues this trend impressively. Like his 2008 String Quartet, it’s cast in two movements: the sprawling opening one that runs about twenty minutes, and a brisk finale that clocks in (here) at just under six. There are some dry moments over the first two-thirds of the former – especially towards the end of its first half, when it feels like McAllister is doing little more than spinning notes (beautifully, it must be said) – but, overall, the piece leaves a tight impression: at this point in his career, Adams’ sense of musical development and drama is strong as ever.

While not really marking any major stylistic developments (as does The Gospel According to the Other Mary), Adams’ Saxophone Concerto is a significant addition to the repertoire and is poised to become a cornerstone of the classical saxophone repertoire.

*****

The first movement of Howard Hersh’s Concerto for Piano and Ten Instruments opens in prime, attention-getting fashion: thunderous, repeated middle C’s interrupted by wild flourishes that suggest a piece that might head, stylistically, in any number of directions. But when the orchestra starts playing, it jumps in with a mixed-meter folk dance, pretty much the last thing one is led to expect. It’s a surprising contrast worthy of Beethoven and indicative of the smart, all-embracing ethos of the music on this album and its composer.

Hersh, like Adams, hails from northern California, and, as in City Noir, the music on his new album, Angels and Watermarks, embraces polyglot West Coast culture in various ways. Stylistically, it’s difficult to pigeonhole: while his music’s overriding qualities might be lyricism and rhythmic energy, Hersh doesn’t shy away from pungent dissonance or from gnarly, angular gestures. He seems to revel equally in all things and if, on occasion, that leads to discursive writing and moments of excess, who cares? There’s an inherent goodwill to this music that goes a long way to mitigate such passages.

The opening piece, the Concerto for Piano and Ten Instruments, gets an incisive, attentive performance from pianist Brenda Tom and an ensemble conducted by Barbara Day Turner. After the lengthy first movement, the second provides a somewhat relaxed contrast, the tempo still brisk and the mood bright. The finale is a bit more complex in tone, but doesn’t depart too far from the spirit of the previous movements. At the end, the music simply tapers off: various notes gradually coalesce around a single E natural and the concerto fades away, enigmatically. As at the beginning, it’s another welcome, unexpected surprise.

This is a concerto as much for the ten instruments as it is for the pianist and the focus of the accompanying group never flags. Pianist Tom plays dexterously and with great accuracy. There are times in each movement when the keyboard’s sound is a bit too stiff and pointed – it would be nice to hear this piece played on a more sonorous instrument or, perhaps, to relax the tempo in spots to allow the performance to speak more naturally – but that complaint takes nothing away from the technical aspect of the reading.

Angels and Watermarks’ title composition, a score for solo harpsichord, follows. Its outer movements share material: “Before (Angels)” and “After (Watermarks)” alternate spidery melodic strands and broken, diatonic chords that lead to some strange, unexpected places. In the second movement, “Flying Lessons,” Hersh writes such brisk tempos that the harpsichord comes to sound like a demented synthesizer – the ghost of György Ligeti is never far removed. The third, “Little Angel Dreams,” begins as a gentle, ragtime lullaby before turning folksy. Throughout, Hersh’s writing emphasizes the instrument’s lute-like qualities. Much the same can be said for the fourth movement, “Touch,” which channels the spirit of any number of Bach toccatas with the chill energy of Terry Riley and Lou Harrison.

In all, it’s an inviting piece and a refreshing break from the traditional harpsichord repertoire. Again, Tom plays with remarkable, almost mechanical precision. Dynamics on a harpsichord are a relative thing (the score actually doesn’t indicate any), but articulation is another matter, and Tom’s attention to things like the staccato-against-legato patterns in “Flying Lessons” brings Angels and Watermarks vigorously to life.

Of a completely contrasting nature is the closing track, the hypnotic Dream, for solo piano. Here, at last, Tom has music she can take her time with, and she plays it beautifully. As a score, Dream is utterly simple, basically repeated iterations of a single, long-breathed melodic phrase. Just before it ends, Hersh introduces a passage of richly dissonant chords over a C major pedal point. It’s the sort of thing I wouldn’t have minded hearing more of throughout the piece, but the single appearance fit with similar moments in the earlier works on this disc: the little, surprising twist.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Absolute Jest, Angels and Watermarks, City Noir, Concerto for Piano and Ten Instruments, Howard Hersh, John Adams, Nonesuch