Food Muse: Breaking Bread, Breaking the Ice

If you want to know what’s for dinner in the Middle East or Africa, look no further than this marvelous book. Here a Persian dish of eggplant with saffron and yogurt, there a Ghanaian soup of chicken and ground nuts scooped up with a dumpling called fufu, there a Lebanese stuffed grape leaf from Arnold Arboretum.

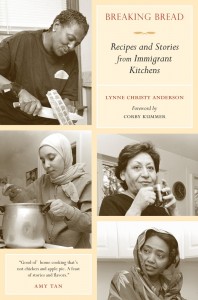

Breaking Bread: Recipes and Stories from Immigrant Kitchens by Lynn Christy Anderson. University of California Press, 304 pages, $24.95.

By Sally Levitt Steinberg

How do you get clammed up people talking? Ask them what they fix for dinner. That’s what Lynne Christy Anderson did, and before you could say spanakopita, her shy ESL students were spilling out stories of their foods from Cape Verde or Sudan or Russia, cooked in the kitchens of Boston. And bringing in their dishes. In Lynne’s book, Breaking Bread, a Persian woman says, “I think food is a great icebreaker.”

How do you get clammed up people talking? Ask them what they fix for dinner. That’s what Lynne Christy Anderson did, and before you could say spanakopita, her shy ESL students were spilling out stories of their foods from Cape Verde or Sudan or Russia, cooked in the kitchens of Boston. And bringing in their dishes. In Lynne’s book, Breaking Bread, a Persian woman says, “I think food is a great icebreaker.”

Lynne says, “I started teaching ESL, looking out to the sea of faces from El Salvador and China, and thinking they seem frightened to be here and afraid of me. We needed a common language and that turned out to be food. Before I knew it they were telling me where to get the ingredients.” From this she wrote Breaking Bread, a book of Me and You and Everyone We Know and their foods, from 25 cultures. She has burrowed into the issue of food as signifier, identifier, communicator, unifier. “Food is our common language.”

I am sitting on Lynne’s back porch on a hot July day, overlooking a tumbling garden of flowers and greenery, slightly helter skelter, things growing as nature intended.

Hanging over the porch is a set of reddish cutlery carved from wood and oversized, as if from Alice in Wonderland, with the mushroom that made you grow taller or shorter. Lynne tells me her husband the hydrogeologist is a woodworker by moonlight, and he carved it for her as a birthday present. “He is an environmental scientist. He does a lot of computer programming. He understands ground water systems. His passion is woodworking”—shop class as soulcraft. The house has a lived-in look, part ramshackle, part historic and venerable. It’s an 1840 house, and a work in progress. Inside are beautiful old wooden floors and doors with carved reliefs. Lynne tells me that her husband is restoring it on Fridays.

The mock fork and spoon align with the book, where the world of food, in all its multicultural splendor, is writ large and imbued with dignity, but retains its good humor. They comment on and celebrate the book and Lynne’s passion with a smile, an exclamation point in wood, tangible, visual evidence, a metaphoric blurb. Rustic, rough hewn natural materials are made into utensils that are what they are, but with a gentle wink. They are humorous and appealing in the way of things that are out of proportion to their real size. They are made of that basic material, wood, the material of the table.

Like food, they are of a growing thing, the tree, common to all cultures, whether fir or jacaranda. The tree provides and symbolizes, it figures in folk tales and myths the world over. Like food, it has tales to tell and substances to give, resins and wood, sap and bark. And like the foods of the book, the tongue-in-cheek place setting is basic and at the same time sophisticated, simple material artfully wrought and resonant with associations and meaning.

Hanging over author Lynn Christy Anderson

Above all the wooden place setting draws attention to the world of food. In this yard, it announces Lynne’s involvement in the world of foods of everywhere in Boston, foods of people who have landed here at the call of opportunity and necessity and family and freedom, in flight from poverty and violence in some cases, and in pursuit of a better chance for their children even if it means sacrifice for themselves and giving up a life that offered more in the way of succor and community. What is Boston made of? Boston is now made of the world—a stewpot beyond Brahmins and Irish and Italians. Ethiopians mingle with Moroccans and Costa Ricans and Chinese.

Through this looking glass, Boston is also made of foods of the world and the customs surrounding them. Cape Verdean Katxupa, pork with corn and beans, and Ghanaian Nkatekwan and Fufu (plantain flour dumplings) and Ethiopian Yebeg Wot, lamb stew for Easter. We get a glimpse of Italy, in the story of an old house by the sea that affords a cool spot in summer for lunch, old-style, not high fashion Italian glitz. These tales that are true stories are from tropics and woodlands, from the fabled minarets and souks of Isfahan, from the high, forested ground of Latvia near the Baltic with mushrooms growing in the brush. This is the world, the world of everywhere on earth.

And from this everywhere emerge foods that behave like Proust’s madeleine, calling up moments from the past in places long ago, or more recent, but certainly far away. The first is from Lynne herself, from her grandmother. “My grandmother would roll pastry dough for lemon meringue pie. It’s sort of a forgotten dessert, no one talks about it anymore, but I love it.” A recognizable American food we take for granted, but that could be seen as “typical,” indigenous.

Lynne conjures up her childhood, the shining peaks of meringue, her grandmother mulling over whether there was enough lemon, or whether the crust turned out right, and choosing a crystal plate for Lynne with a slightly larger piece. Lynne says that when she worked as a chef, “a piece of the past is what we really wanted to eat.” She says that Barry from Ireland is always in quest of the “perfect potato, he’s very serious, he wants to find that flavor from home.”

Beatriz makes Guatemalan tortillas with Juan Antonio, left, and Alejandro. Photo: Robin Radin

Then we are plunged into another world, a hunt for grape leaves in Arnold Arboretum, with a Lebanese mother and child, and a grandmother poking the underbrush with her cane, and speculation about whether a goat has just passed by. We hear the refrain repeated by many from many cultures, about time—people here just don’t have time to prepare dishes like stuffed grape leaves, to prepare them the right way or the traditional way.

In this book about the food of immigrants you have the sense that the way of food is the way of nature and of human culture as it grew naturally. Foraging with her family for mushrooms on Cape Cod, a Russian woman says, “When you forage, it’s a contemplative state of mind. You’re outside with nature.” She talks about getting her kids to pay attention to the ground and its topography, and to the play of light. She says it’s not the result but the process of foraging that is the reward. “You can think about life and talk to each other.”

We watch Zady, a human force of nature, a strong man from Ivory Coast, an “iron chef” cooking at home, saying that in his country cooking is like playing drums. “You just do it. You can’t learn it…If you tell them you’re going to school to become a chef, they will laugh.” He is full of village wisdom, saying that the woman who cooks will attract men. “Your man will always stay where the good meal is.”

Genevieve waits for the groundnut stew, a specialty from Ghana, to simmer. Photo: Robin Radin

But there is another side to him. The women do the cooking in his home country. They would not believe that he cooks, especially for his girlfriend. Zady defies the tradition of women’s hegemony in the kitchen, presiding over a realm ruled by matriarchy where he comes from. He expounds on the freedom he has here–to cook, and not to use his education in his work as a contractor. Wait…what? You heard right. According to custom in his country, he would have had to take a fancier job, perhaps drive a Mercedes, otherwise it would be considered a waste of education. He feels lucky to be able to put his “diploma in the drawer” and go into the street in dirty clothes, to have the privilege of reverse mobility so that he can survive and “help the country.” Shop class as soulcraft again, in the life of a contractor from Ivory Coast.

Lynne, a New England local, has a folksy natural way, not pretentious or self-consciously literary. The fork and spoon go with this style. She is spontaneous, warm, a storyteller. She has a degree in Applied Linguistics. “I knew I wanted to teach ESL. It’s a well kept secret they are the most rewarding. They are thankful to be here.” She has also cooked at high end Rialto. “I loved working with the amazing ingredients and learning culinary techniques. Eventually, I concluded that I didn’t want to spend my time cooking for people I couldn’t sit down at the table with. It started to bother me that some of the dishwashers could never afford to eat there. I became friendly with one of the prep cooks, a woman from El Salvador. We started talking about Salvadoran recipes, and the simplicity in preparation interested me at a time when so much effort and time was spent on dishes at the restaurant.”

Then, without recipes to work with, since most of these cultures don’t use them, she embarked on writing a cookbook. In these cultures, people cook by smell. There is no reverence for the authority of print—if you can read it you can do it is not their way. Lynne watched and reconstructed the dishes that come from centuries of tradition in places where kids stand next to their mothers and watch and smell. Maybe we’d all be better off if we stopped to smell the aromas from the kitchen. It’s about sensory immediacy–the senses are in full use and trusted.

If you want to know what’s for dinner in the Middle East or Africa, look no further than Breaking Bread. Here a Persian dish of eggplant with saffron and yogurt, there a Ghanaian soup of chicken and ground nuts scooped up with a dumpling called fufu, there a Lebanese stuffed grape leaf from Arnold Arboretum. Kedjenou—have you heard of it? Now you can cook this chicken and okra dish from Ivory Coast. Each chapter views a culture through one person or family. Lynne sets the scene in a written sketch in a kitchen or the woods or a market. Then an oral history of food and culture and personal experience follows in the voice of the person profiled. Recipes appear at the end of the chapters.

Fausta and her mother adjust the seasoning for fettuccini. Photo: Robin Radin

Lynne says, “It’s not just my book, it’s their book. It’s more than a cookbook. The stories are a big part of it. They are proud of it. They say they came here with nothing and now there’s a book. ‘People are interested in my story, and they are cooking my food.’” Food was “a way to connect with students. They love to talk about their food.”

In the book you read about local traditions, the foods that people miss not just because of taste but because of the communal place they hold and the rituals surrounding them, their links to the past. The Ethiopian woman talks about the “coffee ceremony.” She says, “No matter what, coffee is the one thing that I will always keep.” In Ethiopia it takes place “outside in the grass with incense. They serve it with popped millet, which is kind of like popcorn.” Sehin says that “back home, people can get together to have coffee.” Here when she has a guest she serves it, but she laments the lack of time (the leitmotif again).

Food is a conduit to human contact. The Filipino woman says, “It’s more than just the food; it’s the connection.” One thread running through the book is that here neighbors don’t drop in for a meal unless it’s arranged. In Italy, there’s a song, Aggiungi un posto a tavola, add a place at the table, for the guest. Fausta says, “Italian women always expect that someone will come,” and she bemoans the fact that Americans don’t. Now she invites people. “There is power in eating together, in sharing,” Dmitra, the Lebanese woman, says.

A Moroccan woman talks about seeing her father kill a sheep in Morocco to celebrate a holiday, and grilling it on the fire. Trying it here with an electric grill, she says—“It’s electric! It’s not so delicious….” She says that even when she cooks Moroccan food here, she can’t enjoy it because they are alone, without family around.

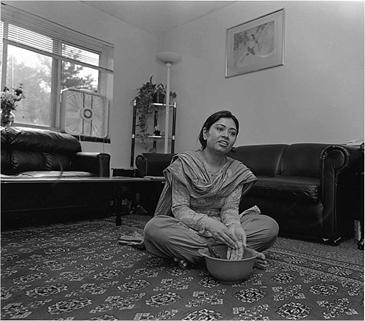

Najia from Pakistan slices onions for biriyani rice. Photo: Robin Radin

Food is one of the few things carried when cultural groups migrate, along with music. Languages give way, with dress and other customs, but food and music, immediate sensory phenomena, survive in new terrain. We leave the homeland, but taste and sound accompany us to new places. Lynne says, “For people who have left so much behind, food is one thing they can hold on to, to give their kids a taste of home. They are immigrants. They are proud of their food. Food is about identity, a place to preserve and show off their culture.”

People from everywhere have sought freedom in the New World, but with loss of community goes a shakiness of identity—most of the people in the book have questions about who they are, with a foot in each world. The Filipino woman says, “And now, I think I’m in between two cultures.” We hear Italian Fausta say that here she is “missing something, like I’m not a whole person.” Old and new cultures tug against each other. There are discontinuities, expressed at the dining table. We listen to a Tre-speaking mother from Ghana, with one child who loves McDonald’s and another who prefers African kenke, a cornmeal cake.

Food, not just for eating, is a cultural marker, a carrier of memory and human ties, and of history. It is a purveyor of meaning. It links us to the past and to each other. Fausta’s cotechino, Italian sausage, has lentils in it. The saying is that the more lentils you eat the more money you will have. Folk wisdom is given its due here, not dismissed as superstition.

“People use food in different ways. Some want their kids to know about cooking. The Guatemalan used her food as a legacy. Why not teach them to cook? She cooks every day with the kids, to bring Guatemala into her house. Johanne from Haiti–her thing was about escape. She watched them set her friends on fire, and she wanted to go back and think about the food of her childhood. She saw food as a way for people to get to know Haitian culture. People use food to remember or to forget. Liz from Brazil uses food as a gift. ‘When you bring food to people you bring a smile to their face and you have the world in your hand.’ For her it’s a gesture of love.”

All of which goes to show that there’s more to food than just food. “I am a big fan of MFK Fisher. She always talks about how food gestures beyond the table.” The book is about what food means in life, as connection, as a spark for memory, as something of value to spend time on, as a way of giving to others. A Lebanese mother says, “That’s how we communicate back home—with food.” It’s not just a dish or a meal, it’s a primal, elemental human experience.

Lynne says, Food is Love. The book shows where the heart lies, and how the dignity of human endeavor finds natural and passionate expression at stove and table, with foods of the homeland, of the family group, binding family with flavors of home, of Russian mushroom patch or Vietnamese banana grove. Zady says, “Whatever my mother made, it was always the best thing of the day.” The Lebanese woman says of her mother, “She cooked from the heart.” There is no stronger adhesive in human life.

Herein lies the tale. Food is us. We are the world.

===========================

Sally Levitt Steinberg is a writer, journalist, and oral/personal historian. She has written several books, including The Donut Book, the world’s definitive book of everything-you-need-to-know about donuts. It was chosen twice as a Book-of-the-Month Club selection; it has been featured in all the media, including NPR, the Martha Stewart radio shows, and the film Donut Crazy for the Travel Channel, and its materials form The National Donut Collection at the Smithsonian Museum.

She has written a biography, The Book of Joy, as well as several personal histories and a book on interior design. Her essay, “Coffin Couture,” was cited as the best piece in the recent anthology of personal history, My Words Are Gonna Linger. She has written articles for many publications, including The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and The New Yorker. She lives in Boston.

Order The Donut Book through the link below to Amazon and The Arts Fuse receives a (small) percentage of the sale.

Tagged: Boston, Breaking Bread, Food Muse, Immigrant Kitchens, Lynn Christy Anderson