Film Review: “Stranger by the Lake” — An Eerie, Stylish Homoerotic Thriller

This death trip romance is powerful, weird, and intoxicating — until its final scenes.

Stranger by the Lake, directed by Alain Guiraudie. At Kendall Square Cinema and other theaters around New England.

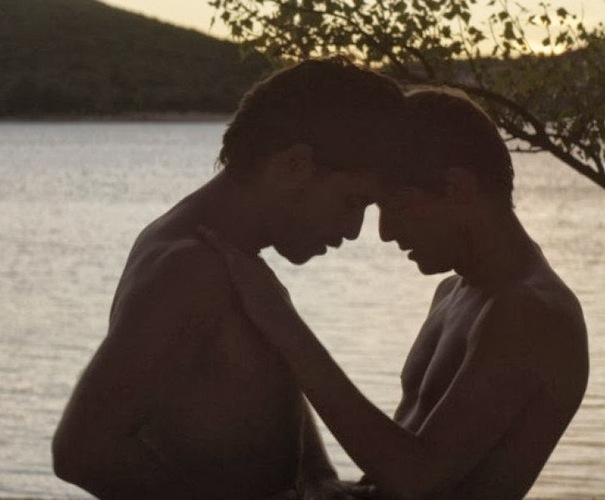

A scene from “Stranger by the Lake” — one of the best French films in several years, cool and cruel like the masterworks of Claude Chabrol.

By Gerald Peary

My critic colleague, Peter Keough, was on point the other day, writing in the Boston Globe. He wondered why reviewers have made such a to-do about the lesbian sex in Blue is the Warmest Color but nobody seems flustered by the male couplings of Stranger by the Lake, also French and more explicit. Boys will be boys, I guess, for most journalists. Well, let me be one to take notice. Stranger by the Lake might be the first non-porno gay film ever in which its protagonist is not only jerked off on on screen, and cums in close-up, but soon after, gives an unfaked, non-body-double blow job. That’s assuredly lead actor, Pierre Deladonchamps, going down on an erect penis.

Director-screenwriter Alain Guiraudie sets his eerie, stylish homoerotic thriller exclusively at a gay cruising site somewhere in rural France. Men pull up in their autos in a parking lot, then wander down by a placid lake. It’s a languid summer, and the long days allow for some swimming, lots of naked, spread-legged, genitalia-showing sunbathing, and occasional trips into the trees and greenery for some body-on-body trysts. Guiraudie shoots all of this straight-faced (gay-faced?), obviously non-judgmental, utterly matter-of-fact. There is no heightened music, actually no music, on the soundtrack. Men deftly go about their business, purposefully but anonymously. Rarely are names exchanged, just lots of bodily fluids.

Franck (Dealdonchamps), is a regular here. Typical of French arthouse cinema, little biographical information is offered about our protagonist. It’s what we might call “celluloid existentialism”: character is what is revealed in the time on screen. We know Franck is a young man between jobs, allowing him weekday time by the lake.That’s his whole backstory. But in our hundred minutes in his movie company, Franck makes consequential moral choices. He becomes complicit in a sordid murder.

The title, Stranger by the Lake, evokes Alfred Hitchcock’s film classic, Strangers on a Train, in which the law-abiding Guy gets pulled into the homicidal lair of amoral, obviously gay, Bruno, who kills on a lark. But how really innocent is Guy? Among other transgressions, Guy hides Bruno’s killing from the police. A plot point repeated by Guiraudie. His two strangers meet not on a train but by the edge of the lake. The movie’s Bruno is Michel (Christophe Paou), hard and muscular, eyes of a lizard, sporting a ’80s porn star mustache. He and Franck check each other out on the shore after they pass in the water. But Michel’s jealous companion — his boyfriend? — intervenes, and takes his man into the woods.

Later that night, Stranger by the Lake converges with the intense voyeurism of Rear Window. In a virtuoso four-minute camera shot, we get Franck’s POV from a hill looking down into the water. He sees, perhaps a hundred yards away, Michel and his lover playing rough in the lake. Michel keeps pushing his companion’s head under. And then there is one! Michel swims in solo. Startlingly unconcerned, he puts on shoes, he towels himself, he walks away to his car. He drives off.

All this time, Franck keeps watching secretly, saying nothing. He doesn’t try to save the drowning man, he doesn’t shout accusations at the stone-emotioned killer. He just takes it all in. And so do we, the scopophiliac viewers, frozen to our seats, our POV exactly the same as Franck’s. What he sees, we see: a murderer killing and walking away undetected from his crime.

In Hitchcock’s oeuvre, the male protagonist’s flirtation with evil occurs on a level of desire, as the villain often carries out his unconscious wishes: i.e., Bruno murdering Guy’s estranged first wife. For the deeply Catholic filmmaker, such deeds in the mind count. We are all sinners, all guilty. In Stranger by the Lake, Franck kills no one. But he goes much farther than the Hitchcockian hero in becoming enmeshed with Michel’s devilish darkness. Michel killing his lover is, in a way, what Franck wants, so he can get Michel for himself. And that what’s happens: instead of turning Michel over to the police, Franck becomes Michel’s new lover at the lake. Though still, essentially, strangers.

Powerful, weird, intoxicating, this death trip romance. And then, sadly, in its last scenes Stranger by the Lake trips up, in a seedy barrage of violence, and with a melodramatic ending leaving us stranded. Too bad for one of the best French films in several years, cool and cruel like the masterworks of Claude Chabrol.

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of 9 books on cinema, writer-director of the documentary For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.