Movie Review: “The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz” — Martyr to Prosecutors’ Zeal?

Aaron Swartz is indeed a martyr, but there’s more here. The film identifies an ongoing battle over control of information as much as it explores a troubled life that ended far too soon.

The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz, directed by Brian Knappenberger. USA, 2014, 105 minutes

By David D’Arcy

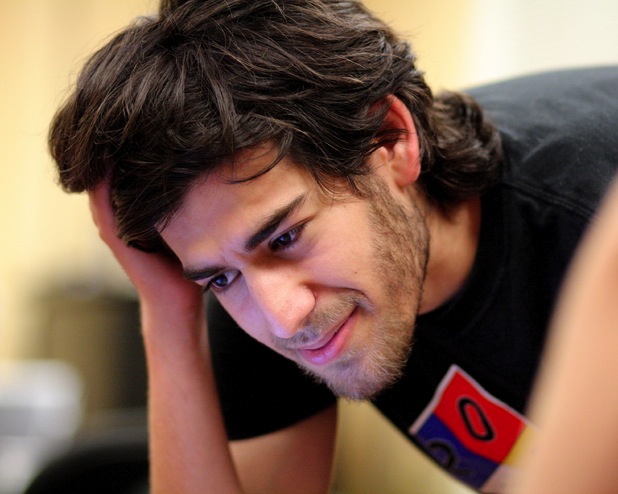

Aaron Swartz killed himself at age 26 in January 2013, after the US government accused him of internet crimes and prepared to throw the book at the soft-spoken whiz kid.

The offenses, downloading academic files (and breaking into a room in which he did that at MIT), were minimal. Compared to the financial misdeeds of massive fraud that went unpunished as they hurt much of the world, his were less than trivial. Swartz still faced serious jail time. Did it all add up? Ask your elected officials.

The Internet’s Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz, a documentary by Brian Knappenberger that distills Swartz’s life and case, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. As you might expect, we witness the rise and fall of the career – maybe we should call it the presence – of a young man who acted on his commitment to the pursuit of knowledge and the free flow of information. Swartz is indeed a martyr, but there’s more here. The film identifies an ongoing battle over control of information as much as it explores a troubled life that ended far too soon.

Swartz, a prodigy at net conferences in his early teens and a Stanford dropout (like Steve Jobs), represents the alternative to the Silicon Valley superhighway to riches. He was part of the team that created Reddit, and he benefited when that idea was sold to Conde Nast for what was then a fortune to him – part of a reported $20 million. But Swartz found the promise of money in the corporate digital world a bore and, more troubling, a moral black hole. He did what he had always done. He turned toward projects that interested him – researching the links between corporate money and the findings of academic researchers publishing in scholarly journals. He and other independent coders, appalled at the cost of accessing court documents and journal articles, found ways to get the material for free and upload it to accessible sites. Sounds democratic. Among their targets were PACER and JSTOR, respectively repositories for federal court filings and academic research.

And Swartz was effective. Fearing that the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) would be a gift to media giants and another potential lockbox for information, Swartz founded Demand Progress, which mobilized the net community against the bill in 2012. Congressmen and senators ran for cover. When Go Daddy, the internet domain registrar and web hosting firm, announced its support for SOPA, thousands of websites decamped overnight. SOPA died (for now), and Swartz had found a way to rally internet support politically – remarkable, given the perception among politicians, if there was any perception at all, that internet geeks were loners in pajamas.

Filmmaker Brian Knappenberger posing for a portrait during the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. Photo: AFP

Getting political meant getting into trouble. Even if the politicians didn’t notice for long, the FBI did.

In the meantime, Swartz took on MIT and JSTOR, the digital library of academic journals, breaking into a utility closet at MIT (also used by a homeless collector of deposit cans) and downloading thousands of articles from the university system. If that’s a crime worthy of the attention of an office of the Department of Justice in Boston, then law enforcement must have a lot of free time on its hands. Bear in mind that these are the people who tried Whitey Bulger, after failing to find him (or to inconvenience those who might have known where he was) for many many years.

JSTOR and MIT ended up dropping the charges. So why would the government go after such a small fish, albeit a hugely talented and a messy uncontrollable one? We get an answer in the film. It’s easier to fight a kid with a t-shirt and a laptop than to go up against a corporate giant – there’s a better chance of winning at trial or intimidating him into a settlement than you’d have in a protracted corporate litigation. And prosecutors with ambitions need victories. Sounds tragically logical to me.

By the prosecutors’ standards, it worked or a while, under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, enacted in 1986, the year that Swartz was born. What the government lawyers got was a frightened and, eventually, a dead genius.

Swartz was intimidated. Was that inevitable? Why did Swartz’s lawyers not staunch the harassment in a battle with the Justice Department that, according to Swartz’s father, cost the family more than $1 million? Why couldn’t they have mobilized the same support for Swartz that defeated SOPA and sent elected officials running to apologize for pro-corporate positions? That mystery remains as a huge net community mourns the brilliant kid.

It’s a moral tale, completed less than a year after Swartz did, and more satisfying as a movie than The Social Network, a failed effort to make the cyber-world cinematic. Don’t look for new formal ground to be broken in The Internet’s Own Boy, yet archival footage from the web’s infinitely expanding picture universe gives the film a special texture. In that web-cam aesthetic, the visual memory of some of the most sophisticated free spirits of the web will take a technologically crude form, but the words and images still give testimony from Swartz and others real poignancy.

And visibility. At least the Swartz side of the argument is there on the screen. Where are the minutes of meetings of lawyers and FBI officials who decided to pursue Swartz? Good luck getting those in what Reddit calls its A.M.A. (Ask Me Anything) sessions. (Even Obama did one of those.) Aren’t citizens paying for these law enforcement campaigns against someone who, as one person in the film observes, may have been guilty of today’s version of the crime of not returning his library books? The best that Knappenberger can get from those who pushed him to the edge is a clip from a TV interview with the grinning prosecutor, Stephen Heymann, speaking about another case, who puts it all down to a criminal’s greed and vanity. Neither fits the facts on Swartz.

Be prepared for charges that The Internet’s Own Boy lacks balance. Like many institutional players caught in embarrassing positions, the US Justice Department and MIT (which retreated from pursuing Swartz), wouldn’t be part of the doc’s examination of the facts. Rather than be forced into access journalism, Knappenberger did the right thing in not waiting for them to agree to talk. Had he done that, there would be no film, and the memory of Swartz outside of a circle of activists would move closer to a distant blur.

The documentary points to another accused wrongdoer in the cross-hairs of the Justice Department, Edward Snowden. The shadow of Snowden puts the Knappenberger film in context. Neither Swartz nor Snowden were cashing in on their downloads and uploads. In Swartz’s case, it’s hard to imagine National Security being breached with citizens getting greater access to court documents which are already public. Wouldn’t the people who read them without the burden of paying stiff fees to Pacer risk being better citizens?

In Russia, where hacking is one of the few sports not represented in the Olympics, Snowden may already have had a chance to see The Internet’s Own Boy. It gives him another reason to stay away from home.

Lawrence Lessig on Aaron Swartz

Wired on Aaron Swartz – surveillance video

Mashable round-up of stories on Aaron Swartz

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.