Book Review: “The Good Lord Bird” — History As a Morality Tale, With Wings

There is more than one way to tell the truth, “The Good Lord Bird” reminds us again and again, and many reasons to cloak it in humor.

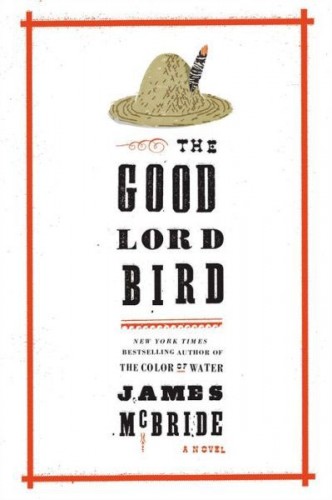

The Good Lord Bird, by James McBride. Riverhead Books, 432 pp. $27.95

By Clea Simon

James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird serves up history as a morality tale, played out in faith and plumage.

That doesn’t mean The Good Lord Bird, a historical novel, is without humor. On the contrary, McBride’s National Book Award winner – his fourth novel – is at times a howler, its message sugarcoated with broad farce. Considering that its subject – the unsuccessful raid by abolitionist John Brown on Harper’s Ferry, a quixotic attack that would spark the Civil War – is both tragic and honorable, that approach is daring. Indeed, its voice – the ungrammatical and often scatological first-person of an unwillingly freed slave – might border on the offensive if the author were not also African American. But despite the idiosyncratic, unconventionally educated voice, the tale evades minstrelsy because of both the protagonist’s unvarnished honesty and the author’s sly wit. There is more than one way to tell the truth, The Good Lord Bird reminds us again and again, and many reasons to cloak it in humor.

Henry “Onion” Shackleford, the fictional protagonist, knows something about disguise. Mistaken for a girl by Brown in the sortie that kills his father and results in his being taken up by Brown’s raiders, our picaresque antihero gives up trying to correct the error when he realizes that being female may just keep him out of battle. Ten years old, he’s slightly built, and Brown isn’t one to give up on a notion once he’s seized on it. Instead, the bible-thumping abolitionist takes Henry – whose name he has heard as “Henrietta” and who is wearing a sack that he mistakes for a dress – under his wing, declaring the child his good-luck charm and giving him a feather of the “Good Lord Bird,” the now possibly extinct ivory-billed woodpecker, as his own token.

What happens next is complicated, despite the hindsight of history. Onion, as he is called, accompanies Brown, a drag Sancho Panza to the abolitionist’s Quixote, in his quest to end slavery. But although Brown is single-minded, the world as Onion sees it is infinitely more varied. Simply put, the issue of slavery – or of race or gender – is not just black and white.

James McBride reading from “The Good Lord Bird” in an evening that also featured his gospel quintet.

For starters, Onion doesn’t want to be free. “I was never hungry when I was a slave. Only when I got free was I eating out of garbage barrels,” he notes early on. Two years later, he is still griping: As a slave, he says, “Your meals is free. Your roof is paid for. Somebody else got to bother themselves about you.” Nor are white people the only ones corrupted by the institution, and one of the most moving passages involves Onion’s stay at a whorehouse where one of the black prostitutes, whom he loves, is as racist and cruel as the white madam who owns them all. Onion’s disguise – the ultimate manifestation of the emasculated black man – has begun to weigh on him, his moral growth emerging with his sexual maturity, and this lack of self-determination, a basic freedom, perverts everyone’s sense of self. It will make fools out of more than one character, including a blowhard Frederick Douglass, who is portrayed as a lecherous drunk. In fact, the one touchstone of virtue throughout the book is a character’s willingness to allow for some fluidity of identity. As Harriet Tubman, one of the few truly noble characters, says, “A body can be whatever they want to be in this world. It ain’t no business of mine. Slavery done made a fool out of a lot of folks.”

The book is not flawless. The trope of oppressed people disguising themselves in less threatening guises is almost too constant, and McBride tends to repeat himself, as when he spells out why such deceit is not only justified but necessary. “The white man put his treachery on paper,” he has Onion say. “Niggers put theirs in their mouth. … Every colored did what they had to do to make it.” Plus, despite McBride’s keen ear for individual voices, the dialect can get wearying at times. But the subtle beauty of this book rewards the reader who stays with it. There’s a lot of heart here, love as well as anger, and redemption, too, in those glimpses where Onion shows his true face. “If you can’t be your own self how can you love somebody?” he asks at last. “How can you be free?”

A former journalist, Clea Simon is the author of three nonfiction books and 14 mysteries. A contributor to such publications as the Boston Globe, New York Times, and San Francisco Chronicle, she lives in Somerville with her husband, Jon Garelick. She can be reached here and on Twitter @Clea_Simon.

Tagged: African-American, civil-war, Clea Simon, historical fiction, James McBride, National Book Award

Disrespecting heroic Brown and Douglas, Mc Bride, unfortunately, runs roughshod over history. Sad. I loved The Color of Water.