Book Review: “The Lair” — The Intoxicating Trauma of Exile

Norman Manea’s compelling novel The Lair tracks the ambiguities, contradictions, and confusions of the exile’s psyche as he struggles to find footing in surroundings that are often unintelligible.

By Tess Lewis

The Lair by Norman Manea. Translated from the Romanian by Oana Sânziana Marian. Yale University Press, 336 pages, $19.95.

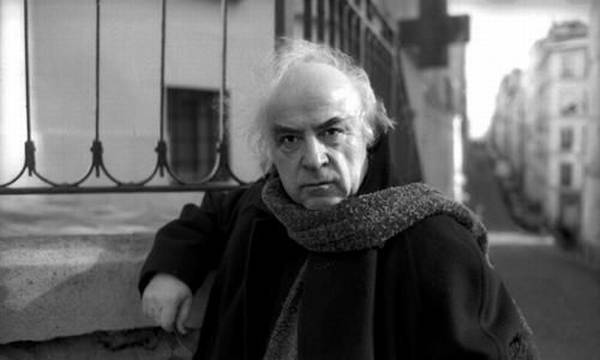

Exile isn’t what it used to be. Norman Manea would know. The most important contemporary Romanian writer, Manea was exiled from his country twice: first in 1941 at the age of five when his family was deported from his native Bukovina to a concentration camp in the Ukraine and then again in 1986 at the age of 50 when he left Romania under Ceauçescu’s dictatorship and settled in the United States. In the 25 years since he definitively left his homeland, the condition of exile has become more common, whatever its causes: economic, political, religious, or cultural. “Our cosmopolitan, post-modern, centrifugal world,” as he describes it, is smaller, people more mobile, nationality more fungible.

Exile isn’t what it used to be. Norman Manea would know. The most important contemporary Romanian writer, Manea was exiled from his country twice: first in 1941 at the age of five when his family was deported from his native Bukovina to a concentration camp in the Ukraine and then again in 1986 at the age of 50 when he left Romania under Ceauçescu’s dictatorship and settled in the United States. In the 25 years since he definitively left his homeland, the condition of exile has become more common, whatever its causes: economic, political, religious, or cultural. “Our cosmopolitan, post-modern, centrifugal world,” as he describes it, is smaller, people more mobile, nationality more fungible.

Still, although the state of exile is more common today, there is little comfort in numbers. It remains a complicated often traumatic condition, especially for those who live by and for language and are unable to master a new one. After a brief stay in Berlin, Manea arrived in the United States speaking almost no English and disoriented by the transition from a society dominated by a complex system of codes that regulated even the most mundane affairs to one that seemed utterly transparent and prone to excessive simplifications. Only a few of his books had been translated into European languages and none of them into English. He carried the Romanian language with him like a snail its shell, both shelter and isolation, and he gradually rebuilt the library he had been forced to leave behind in Bucharest into a protective lair.

These metaphors of exile, the snail and the lair, are at the center of Manea’s new books, his novel, The Lair, and his collection of essays, The Fifth Impossibility: Essays on Exile and Language. (I translated three of the essays in that volume from German versions of the Romanian originals since no Romanian translator was available at the time—more evidence of the linguistic hurdles faced by exiles, particularly those speaking “smaller” language.) These two books are complementary, describing the experience of exile from different perspectives. The lucid, logically reasoned essays explore how Eastern European writers, and especially Manea himself, moved from one culture to another, from East to West, during the Cold War and its aftermath.

For many it was an exercise in frustration if not outright futility. Manea often feared he “had traded [his] tongue for a passport.” Accordingly, the fifth impossibility of the title essay, following the four impossibilities Kafka discerned for the Jewish writer writing in German, is “the impossibility of the snail,” in other words, “the impossibility of continuing to write in exile, even when the writer takes his language with him.” It is a relative, not an absolute impossibility, of course, as attested by these books themselves and others Manea has written in exile, most notably his memoir, The Hooligan’s Return.

Whereas the essays observe exiles from the outside in, the novel moves from the inside out. The Lair tracks the ambiguities, contradictions, and confusions of the exile’s psyche as he struggles to find footing in surroundings that are often unintelligible. It is a highly cerebral, labyrinthine book, filled with mystery, paranoia, and illegible codes. It jumps back and forth between past and present and from one character’s point of view to another’s. At the heart of the novel is a love triangle between three Romanian exiles in the United States, overshadowed by a mysterious death threat. Yet this construct is not so much a plot as a stage on which Manea enacts the existential tragicomedy of Old World intellectuals stranded on the shores of the New World.

The first of these exiles to leave the “Homeland” is Augustin Gora, a man formed by the books he has read and loved. Granted asylum while in the United States on a Fulbright, Gora was able to establish himself in academia with the help of an older, eminent, Romanian émigré, Cosmin Dima, a literary stand-in for historian Mircea Eliade. But Gora has withdrawn completely to his lair of books, his “cell of papyrus” where “the past is present and the present is an echo of the past.” He surfaces only rarely, mostly to write short, ironic obituaries for the émigré press.

To Gora’s surprise, his ravishing, inscrutable wife Lu had refused to leave Romania with him. When she does show up in America years later, after Ceauçescu’s fall, it is on the arm of her younger cousin and lover, Peter Gaspar, a minor literary celebrity who, like Gora, had frequented a clandestine reading and discussion group decades before in Bucharest. But the strain of exile is too much, and Lu soon abandons Peter, too. The hapless Gaspar is comically unemployable. Although utterly without experience driving, he survives a one-day stint as a chauffeur in New York, and his attempt to change a light-bulb in a convenience store lands him in the hospital for major surgery. Gaspar eventually, and almost despite himself, gets a job teaching at a small, upstate New York college closely resembling Bard. He contacts Gora occasionally, but their interactions are obviously tense, both men longing for the absent Lu.

To Gora’s surprise, his ravishing, inscrutable wife Lu had refused to leave Romania with him. When she does show up in America years later, after Ceauçescu’s fall, it is on the arm of her younger cousin and lover, Peter Gaspar, a minor literary celebrity who, like Gora, had frequented a clandestine reading and discussion group decades before in Bucharest. But the strain of exile is too much, and Lu soon abandons Peter, too. The hapless Gaspar is comically unemployable. Although utterly without experience driving, he survives a one-day stint as a chauffeur in New York, and his attempt to change a light-bulb in a convenience store lands him in the hospital for major surgery. Gaspar eventually, and almost despite himself, gets a job teaching at a small, upstate New York college closely resembling Bard. He contacts Gora occasionally, but their interactions are obviously tense, both men longing for the absent Lu.

The unhappy equilibrium that both men have achieved is short-lived. Asked to review Dima’s memoirs, Peter agonizes over how much he should reveal of the “Old Man’s” fascist sympathies and support for the Iron Guard in the 1930s. Not long after a fellow émigré and former disciple of Dima’s is shot dead in a bathroom stall at his university, Gaspar receives a cryptic death threat assembled from a New York Times clipping and a quote from Borges. He begins calling Gora obsessively, mulling over the possible significance of minute details. Former women students become involved—perhaps suspects, perhaps innocent bystanders—as does campus security, the state police, and the FBI.

Lest the plot sound implausible, keep in mind that Eliade did, in fact, avoid discussion of his youthful fascist sympathies; his estranged disciple Ioan Culiano was killed, execution style, in a University of Chicago toilet, and, after writing an essay for The New Republic in which he discussed Eliade’s shady past, Manea, a professor at Bard, was treated to a smear campaign in the Romanian press and received threatening mail. In his essay (included in The Fifth Impossibility) “The Exiled Language,” Manea notes that when isolated from his language, “the exile often swings, for a long time, if not forever between the past and the present. Between formation-deformation-education, between different possible egos until, gradually, the double appears to represent him on the new social stage.” Both Gora and Gaspar represent possible literary doubles, projections of the exile’s ego, formed, deformed, and reformed in the imagination.

This may sound hopelessly elaborate and baroque. It is meant to be and it is, intoxicatingly so when Manea and his translator, the estimable and undaunted Oana Sânziana Marian, succeed in the impossible task of capturing in English the “vagueness, metaphors, wordplay, lacunae, equivocal allusions, ironies, intertextual blurrings, as they are practiced in Romanian literature.” One such moment is a poignant scene towards the end of the novel in which Gora, despairing of ever seeing his beloved Lu again, fondles his collection of gloves, which have come to represent the woman he has lost. “White and black and red, yellow, blue gloves made of leather and silk, out of the skins of antelope and snake, the most expensive wool and the finest cotton, hunted in the windows of the most expensive boutiques on his sickly pilgrimages.” Like a Balkan reimagining of Daisy weeping at the sight of Gatsby’s shirts, Gora surrenders to the pull and the pall of his obsession: “He studied them, he stockpiled them, he brought them out to the light, one pair at a time or all at once, in a moment of fury and ecstasy, such as on this evening.”

It is the September 11th attacks that jolt Gora and Gaspar out of their complacent miseries. Gaspar had disappeared a few days before, and while he may have perished in the attacks—he had an appointment with an immigration lawyer at the World Trade Center that morning—it is just as likely that he used the event to invent a new identity. For Gora, the attacks remind him of the fragility of his “fortress” of books, and he rails against those terrorists too vulgar and illiterate to understand that the Twin Towers were but superficial symbols of the civilization they wanted to destroy. What if they finally realize that their orgy of destruction would be more effective if they destroyed the “library [that] holds everything”?

The memories and projects of the world, the genius and madness of the loyal and the infidels, the Bible of the Jewish prophets and the Qur’an of your own Prophet, and the Testament of the crucified prophet, and Mein Kampf of the fool prophet and the Manifesto of the Marxist prophet. The decrees of the Inquisition and the Proclamation of the Rights of Man, the games of the child Mozart, and of the earless Van Gogh, Homer and Krishna and Confucius, Madame Bovary and Karenina and Mother Teresa, Cassius Clay and the Bucharest phone book of 1936. Everything, everything, even a volume of verses written by the adored Ben Laden, translated into the language of the adored William Shakespeare, the verses of Iosif Visarionovich Djugasvili and his rival Mao Zedong.”

Having escaped the “legalized bliss” of one former utopia, Gora finally embraces America’s “incoherence” as “its greatest realization.” Its embrace of conflicting points of view and resistance to one absolute systems of thought is its protection against the terrorists’ morbid “perfection, magic, utopia.”

Only gradually and after many dark nights of the soul did Manea emerge from the snail shell of exile and realize that his condition had metamorphosed from a handicap to a “beneficial uprooting,” an occasion for rebirth with resources to overcome the fifth impossibility. These two volumes are his provocative certificates of rebirth.

Tess Lewis is an essayist and translator from French and German. Her translations of the Swiss poet Philippe Jaccottet’s Seedtime: Notebooks 1954-79 was published recently by Seagull Books . She is curator of the 2014 Festival Neue Literatur.

Tagged: essays, fiction-in-translation, Norman-Manea, Romanian, The Fifth Impossibility