Classical Music Review: Pianist Victor Rosenbaum

Reviewed By Caldwell Titcomb

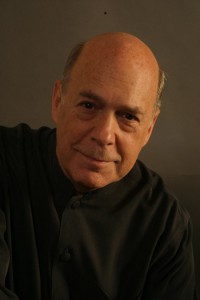

Pianist Victor Rosenbaum

Among the top pianists who live in our area is Victor Rosenbaum (b. 1941). A faculty member of the New England Conservatory since 1967 (and a former chair of its Piano and Chamber Music Departments), he was also president of the Longy School of Music for 16 years (1985-2001). He teaches at the Mannes College of Music in New York, and concertizes and gives master classes throughout the world. His February 11 recital in Jordan Hall was widely anticipated and drew a large audience.

He began with Haydn’s Variations in F-Minor (Hob. XVII:6), a remarkable work new to me. Written in 1793, this is a lengthy piece, lasting 18 minutes. It keeps oscillating between the minor and major mode, ending in the major. Containing striking Neapolitan-sixth harmony, it features toward the end unexpected ascending chromaticism. In keeping with the period, Rosenbaum never exceeded a dynamic level above mezzoforte.

Proceeding to Haydn’s sometime student Beethoven, Rosenbaum brought a long familiarity with the composer. In recent decades he has made something of a specialty of the last three piano sonatas (Op. 109, 110, 111), recording them on a masterly CD in 2004 (he already played Op. 109 superbly as a college undergraduate). This time he backed up to Beethoven’s early period with a performance of the Sonata in C-Major, Op. 2, No. 3 (1794-95), composed not long after Haydn (who was the work’s dedicatee) wrote the previous piece.

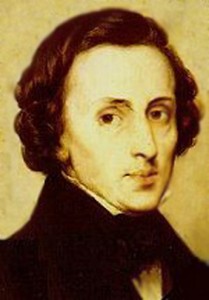

This year marks the bicentennial of Chopin's birth.

The sonata-form first movement wanders afield in the exposition’s second group. Toward the end there are rhetorical pauses—a device that would become a hallmark of Beethoven’s style. The slow movement is in the rather unexpected key of E-major. The C-major scherzo has a trio in A-minor. The finale is a lively rondo with its own surprises. Rosenbaum caught all its moods whether serious or humorous.

This being the bicentennial of Chopin’s birth (1810-49), Rosenbaum devoted the entire second half of his program to this master of piano composition. Of the four wondrous Ballades, he chose the third in A-flat major, Op. 47 (1841). This starts off simply enough but becomes technically demanding as it proceeds. Of Chopin’s fifty-odd mazurkas, Rosenbaum gave us two: Op. 50, Nos. 2 & 3 (1842), both relatively long.

The pianist ended with the beautiful C-sharp minor Nocturne, Op. 27, No. 1 (1835) and the equally beautiful F-sharp major Barcarolle, Op. 60 (1846). He was enticed to play two encores—another pair of Chopin mazurkas: Op. 24, No. 2 and the curious Op. 17, No. 4, with its harmonically ambiguous conclusion. No other composer has explored more deeply the expressive and technical possibilities of the piano, and Rosenbaum demonstrated this with sovereign mastery. No harshness, no banging.

Tagged: Caldwell-Titcomb, Classical Music, New England Conservatory, piano