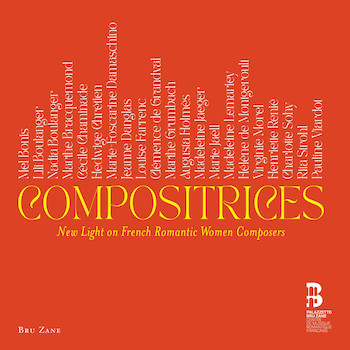

Classical Album Review: “Compositrices — New Light on French Romantic Women Composers”

By Ralph P. Locke

An 8-CD set of diverse and enjoyable works, brought back from obscurity by Aude Extrémo, Roberto Prosseda, and other major performers.

Compositrices: New Light on French Romantic Women Composers

Cyrille Dubois and Yann Beuron (t), Aude Extrémo (mz), Claire Le Boulanger (fl), Roberto Prosseda, Alessandra Ammara, and Nathalia Milstein (p), and other vocal and instrumental soloists.

Capitole de Toulouse National Orchestra, French National Orchestra, Les Siècles, and Metz Grand Est National Orchestra, cond. Leo Hussain, David Reiland, François-Xavier Roth, and Debora Waldman.

Bru Zane [8 CDs] 10 hours 12 minutes.

An astounding treasury has been released by the unique and well-funded Palazzetto Bru Zane (Center for French Romantic Music), whose headquarters are in Venice, Italy. It’s an 8-CD set of very recent recordings (often the first-ever) of little-known works in a wide range of genres. The set bears the polyglot title Compositrices: New Light on French Romantic Women Composers. (“Compositrice” is a relatively new coinage, giving “compositeur” a feminine ending. This sounds less bizarre in French than, say, “composeress” would in English.) The excellent and nuanced introductory booklet-essays by scholars Alexandre Dratwicki and Etienne Jardin indicate that two works were recorded before: Louise Farrenc’s Symphony 3 and Augusta Holmès’s symphonic poem Andromède. In fact, there are at least a few others, including Farrenc’s Piano Trio 2, Op. 34, in E-flat (once available on LP; a new recording was reviewed, and praised by in American Record Guide, as “sophisticated, intricate, and graceful”), the “Night and Love” interlude from Holmès’s Ludus pro patria, and the well-known Flute Concertino by Cécile Chaminade. Still, perhaps 8 of the 10 hours’ worth of music heard here has not been heard in a century or more, never mind recorded.

Glancing at the contents of the various discs, in which certain performers keep recurring, one might think that the box is an assemblage, reshuffled, of recordings previously released on individual CDs. In fact, though, all the recordings were made in the past few years and saved up for this special release, which I should stress is available online for around $50: around $6 per disc.

Twenty-one composers are represented. Each of the eight discs has been arranged as a kind of “sampler” concert, alternating orchestral and chamber-ensemble pieces with piano-accompanied songs. But I should make clear that we hear mostly complete works, not isolated movements. The total timing of each CD is listed on the bottom of its sleeve.

This “sampler” arrangement encourages serendipitous listening: one may put on a disc because it has a relatively better-known composer on it, or because it begins with something you’re in the mood for, such as songs (perhaps sung mellifluously and thoughtfully by Cyrille Dubois, the most frequent solo vocalist here) and then be pleasantly surprised by a cello sonata, piano quintet, or movement from a large oratorio-like opus.

Four fine orchestras are involved, including the French National Orchestra and the period-instrument Les Siècles (the latter under its renowned conductor François-Xavier Roth). The recorded quality is excellent, though, inevitably, the acoustics vary with the hall and the performing group. A piano generally sounds more close-up in solo works, and then the mics move back if the next piece has piano plus a singer or string player.

Tenor Cyrille Dubois. Photo: Wiki Common

A full appreciation of this harvest offering could perhaps find place at some kind of public conference/celebration, at which a dozen specialists would expatiate on the various genres and individual composers, elucidating, with sound clips, the many pleasures and surprises to be found in the boxed set. Instead, we are given nothing but a 100-page booklet — which may sound substantial, but it’s far too thin for the purpose, since everything is printed in three languages (in the order English/French/German), and many pages are devoted (understandably enough) to photos of the composers and performers and to listings of the members of the four orchestras.

We could have used a brief commentary on each of the pieces: what its title refers to, how it fits into the composer’s output and relates to other pieces in that genre, and whether it got performed and reviewed during the composer’s lifetime. For example, listeners will wonder just how programmatic Mel Bonis’s Ophélie was meant to be: should we imagine the innocent young Dane conversing with Hamlet, or going mad and offering a flower to the queen, and/or, finally, drowning in the river as she sings? (The piece is included on two different CDs, once in the piano version, the other time in the composer’s own iridescent orchestration. Even more fascinatingly, a three-minute song by Jeanne Danglas is given also in Danglas’s arrangement for orchestra without voice.)

And we absolutely should have been given the sung texts of the vocal works, at the very least in French, and ideally also in English and German. We do at least get excellent short biographies of each composer, often more complete and reliable than what one can find anywhere else, whether in print or online. (A major reference book on French women composers, by Florence Launay, appeared in French in 2006 — its title likewise begins with the intriguing word “Compositrices” — and has never been translated. By now, it deserves to be substantially revised, if the publisher, Fayard, will permit this, and then translated into English!)

In some cases, the listener can repair the lack of printed texts by searching online, such as at www.lieder.net (which has some 42,000 generally reliable song translations!). One clue: some of the songs here use the same texts that were set by, say, Fauré or Debussy. And often the “new” setting feels just as apt and engaging, showing the text in a new light. Still, I hope that the devoted staff of the Palazzetto Bru Zane will upload all the song texts to their amazing, copious website (www.BruZaneMediabase.com/en ), even if only in French, as they have done for one piece by Nadia Boulanger (see below).

Augusta Holmès. Photo: Wiki Common

Enough carping, though, for there are amazing riches to explore here! Some composers are already semi-familiar (Farrenc, Chaminade, Lili Boulanger). Some published under gender-obscuring pseudonyms or shortened names: Charlotte Durey published under her maternal grandfather’s name, Charles Sohy; Mel Bonis was born Mélanie; and Marie-Foscarine Damaschino turned herself into Mario Foscarina. (Perhaps the final a in the pseudonym hints obscurely at the secretive gender switch!)

Some composers, like Farrenc and Chaminade, got their works published and performed and were honored with awards and professional positions. (Farrenc taught piano at the Conservatoire.) Others ended up writing for the desk drawer. Virginie Morel, who, the composer Méhul thought, had the makings of a major pianist, ended up spending ten years in French-colonial Algeria when her soldier-husband was posted there, after which they settled at his family’s provincial chateau. She managed to publish a few works, but what more might she have done musically if she had lived most of her life in Paris or Lyons?

Many of the scores used here have been prepared for performance and recording by Bru Zane’s indefatigable team, led by Alexandre Dratwicki, Étienne Jardin, and Sébastien Troester. Fortunately, most of the works can now be found on the Petrucci site (www.IMSLP.org). BruZane will help provide materials to enable further performances. Additional information on many of the composers is at the aforementioned site.

And how do the works hold up? Thanks to the mostly excellent performances, well indeed! The entire eight discs held my attention, though partly because I listened to just a work or two at a sitting, often choosing two works that I thought might relate to each other or might contrast interestingly.

The aforementioned Charlotte Durey-Sohy (who had a mutually supportive musical marriage with composer Marcel Labey) is praised, in the biographical sketch, for her vocal works. And justly so, if the three confident, grandly scaled songs (to her own evocative poems) that end CD 1 are any indication. Her Symphony in F-sharp minor (1917) grabbed me even more, not least for its colorful commentary from individual wind instruments while the main musical debate is often being carried out by the strings. Perhaps there’s a relationship between the lyricism in her vocal music and the melodiousness in her writing for winds? She offers a tight, cogent three-movement piano sonata here as well.

The several works for piano four-hands are precious reminders of musical life in the French salon, much like better-known four-hand works by Bizet, Fauré, Debussy, and Ravel. Marie Jaëll’s four-hand Voix du printemps (Springtime Voices, 1885) is harmonically and rhythmically adventurous, like so many other of her works, yet also feels like a heartfelt tribute to the music of Schumann. (I praised a 3-CD box of Jaëll’s works, including a splendid cello concerto here.) Mel Bonis’s 1930 set of six shortish four-hand pieces presumes that one of the players is a student; thus it keeps her or his music much easier. The pieces are all descriptive, e.g., “Caravan,” “Habanera,” and “The Great Clock Strikes Midnight.”

Pauline Viardot comes off as a major presence here. She was known to be the century’s greatest mezzo-soprano, but also was a first-rate pianist, and friend to many major composers. We are treated to a delightful Sonatina for violin and piano, in three concise and contrasted movements, and two groupings (on different CDs) of songs in French or Spanish, sung with masterful control and insight by Aude Extrémo, a singer I have admired in Spontini, Offenbach, and in the grand opera Herculanum by Félicien David (viewable on YouTube.com).

Mel Bonis. Photo: Wiki Common

The artistry on display here can be illustrated by CD 3. It begins with a group of five masterful piano pieces by the aforementioned and long-lived Bonis (1858-1937). All five were published by such firms as Eschig or Hamelle in various years between 1895 and 1923. The titles are evocative and match the mood and figuration of the music: “Barcarolle,” “The Damaged [literally Wounded] Cathedral,” “Song without Words,” “At Dusk,” and “Song of the Spinning Wheel.” The cathedral piece was a response to World War I (which had begun in 1914, the year before). Bonis evokes the church in part through repeated, imaginative use of the opening notes of the famous “Dies Irae” theme (it appears also in works by other composers such as Berlioz, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff). These Bonis pieces are splendidly conveyed by François Dumont, a pianist I’ve never heard of. (Indeed, many of the performers here are new to me, and all present themselves admirably.) I should add that Bonis’s “Spinning Song” (another way to translate “Chanson du rouet”) sounds very guitaristic to me—as if Bonis were somehow melding Mendelssohn’s “Song without Words,” op. 67 no. 4 (which bears the nickname “Spinning Song”) with the long-beloved “Asturias/Leyenda” (1892), a guitar-like piano piece by Isaac Albeniz (often played, almost unchanged, on guitar!), and creating, in the process, something fully original and satisfying.

Bonis’s piano pieces nicely lead, on CD 3, to a piece for violin and piano (Anna Agafia and Frank Braley, both immensely gifted and communicative): Lili Boulanger’s “D’un matin de printemps” (One Morning in Spring), a work that the composer later arranged several times for other instrumental combinations. It is a joyous and energetic work, ending with a virtuosic whoop, not at all what one might expect from a composer who suffered from illness most of her life and died in 1918 at age 24, shortly after completing the orchestral arrangement of this life-affirming music.

CD 3 continues by assembling an orchestra (in the Arsenal hall in the city of Metz) for the Farrenc Third Symphony. The work has been hailed by British critic Tom Service, who knew it from two recordings (Johannes Goritzki, Stefan Sanderling). There has also been a period-instrument recording led by the female conductor Laurence Equilbey. David A. McConnell says (at theclassicreview.com) that Equilbey’s performance, with a period-instrument orchestra, emphasizes the work’s “emotional depths and bold orchestration.” The American Record Guide critic, Gil French, has called the work “superb” — indeed has proposed that all three Farrenc symphonies are “easily the match for most of Schubert’s and almost as good as Schumann’s, and their strength of temperament is a close match to Beethoven” (November/December 2023). I know the Third only in this new recording, and find that Farrenc’s admiration for Mozart and Beethoven is vividly on display (the Eroica in mvt. 1, the Mozart G-minor in the finale; Gil French hears Beethoven’s Fourth, which seems just as likely). The reading is transparent, and the Metz orchestra, led by David Reiland, sounds small but very alert.

The orchestra departs, and a cellist and pianist (Victor Julien-Laferrière and Théo Fouchenneret) bring us three marvelous short pieces by Nadia Boulanger from 1914, when she was only 27: she would go on to become a renowned organist, conductor, and most of all teacher to Copland and Piazzolla and decades-long advisor to Stravinsky. The three pieces have no titles; all are in the minor mode, and the second is built around a melody played in canon between the cello and the pianist’s right hand, perhaps evoking the beginning of the last movement of the Franck Violin Sonata (though that’s in the major). The third piece has a martellato feeling, a bit like some Bartók, and features a middle section reminiscent of early Manuel de Falla (without quite sounding Spanish). The three pieces together last less than six minutes and would make a marvelous addition to any cello-piano recital. (CD 6 contains the aforementioned large-scale and highly dramatic cantata by Nadia B. for soprano, mezzo, tenor, and orchestra, entitled La Sirène. This work won her a second prize in the 1907 Prix de Rome competition. The text is long and high-toned; one can find it online, alas only in French, at the site of the Palazzetto Bru Zane’s Center for French Romantic Music.)

Disc 3 concludes with the Introduction and “Song of Sadness” [or “Pain” — the word is douleur] from Marie Jaëll’s secular oratorio (if that is the best genre description for it) Ossiane (1879), a long and complex work to a text by the composer that is, as far as I know, unpublished. Ossiane had one public performance in Jaëll’s lifetime and has perhaps never been heard entire since then. The imaginary character in the work’s one-word title is a female philosopher-poet who goes on a spiritual search through the universe. Her name is essentially that of the legendary Scottish bard Ossian, but given a feminine ending. If the work were in Italian, the name Ossiane would be Ossiana. Liszt was a great advocate of Marie Jaell’s compositions and addressed her in letters as “Dear Ossiana” or sometimes “Dear Admirable One.”

Marie Jaëll. Photo: Bru Zane

The introduction to Ossiane is a stirring miniature symphonic poem, very much in the manner of Liszt’s works in that genre, with dark, brooding orchestration and much use of unsettled diminished harmonies. The “Sorrow” aria for soprano is full of yearning and soaring — what I wouldn’t give to hear the whole work! The soprano here, Anaïs Constans, is at once pure and inspired. I have praised her in quite diverse operas: by Cherubini, Saint-Saëns, and Offenbach.

The writings in the booklet are sometimes translated too literally. For example, “a transversal exploration” here should instead have been something like “when listening to a cross-section.” (The French language delights in somewhat abstract-feeling nouns, but good English prefers active verbs, as the old book by Strunk and White wisely recommends.)

Despite the limitations of its booklet, this 8-CD box needs to be heard by singers, instrumentalists, conductors, and concert organizers, and will delight and healthily challenge anybody who thinks s/he already knows what the Romantic and post-Romantic eras have to offer.

With regret at not being able to discuss all the works on these discs, I close by at least naming the eight composers I haven’t yet mentioned: Marthe Bracquemond, Hedwige Chrétien, the Vicomtesse Clémence de Grandval, Marthe Grumbach, Madeleine Jaeger, Madeleine Lemariey, Hélène de Montgeroult (some of her major piano works have been much praised by record critics recently), and Henriette Renié.

I notice that two of the lesser-known composers in the 8-CD box, Charlotte Durey-Sohy and Rita Strohl, have just had releases devoted entirely to them. Étienne Jardin, a key member of the Bru Zane team, published a collectively written book about Mel Bonis in 2020. The world is finally ready to give these and other women composers their belated due — thanks to the efforts of imaginative performers and record labels. The harvest is quite impressive and leads me to wonder what other works by forgotten figures (whether female or male) have been unjustly left by the side of the musical road for whatever combination of reasons.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is part of the editorial team of Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal, an open-access source that includes contributions by performers (soprano Elly Ameling) as well as noted scholars (Robert M. Marshall, Peter Bloom) and is read around the world. The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Alessandra Ammara, Alexandre Dratwicki, Aude Extrémo, Augusta Holmès, Bru Zane, Cécile Chaminade, Claire Le Boulanger, Cyrille Dubois, Etienne Jardin, French National Orchestra, Les Siècles, Louise Farrenc, Marie Jaëll, Mel Bonis, Metz Grand Est National Orchestra, Nathalia Milstein, Roberto Prosseda