Opera Album Review: Luigi Cherubini’s “Les Abencérages” — Revving up Romantic Grand Opera

By Ralph P. Locke

First presented in 1813, Les Abencérages displays the mastery and inventiveness of the renowned composer of the opera Medea.

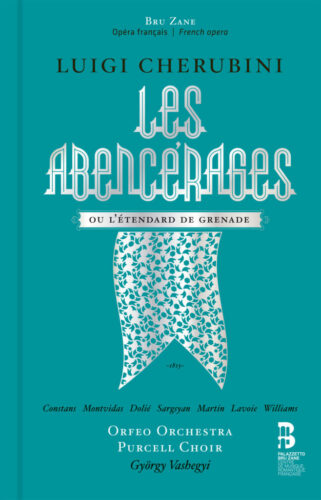

Luigi Cherubini: Les Abencérages

Anaïs Constans (Noraïme), Edgaras Montvidas (Almanzor), Thomas Dolié (Alémar); Artavazd Sargsyan (Gonzalve and a Troubadour), Philippe-Nicolas Martin (Kaled), Tomislav Lavoie (Alamir).

Orfeo Orchestra, Purcell Choir, cond. György Vashegyi.

BZ1050 [2 CDs] 169 minutes

To purchase or to hear some tracks, click here.

The long-lived and prolific Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) was renowned in his own day, mainly for his operas and sacred music. But music lovers over the past century or so have tended to know just a few of his works, such as the Symphony in D Major and the Requiem in D Minor. Both of these were recorded by Toscanini. (See my review of two wildly different recordings of the Requiem, under Giulini and under Niquet.) Plus the opera Médée, which is generally done in Italian (as Medea), with extensive and very dramatic recitatives composed over fifty years later by Franz Lachner (to a German translation). The Lachner version, Italianized as usual, is what the Met used a few months ago, wonderfully sung and played. There are several audio recordings of that version featuring Maria Callas in the title role (one conducted by a youngish Leonard Bernstein), and even some video excerpts (the latter vividly conducted by Thomas Schippers).

The long-lived and prolific Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842) was renowned in his own day, mainly for his operas and sacred music. But music lovers over the past century or so have tended to know just a few of his works, such as the Symphony in D Major and the Requiem in D Minor. Both of these were recorded by Toscanini. (See my review of two wildly different recordings of the Requiem, under Giulini and under Niquet.) Plus the opera Médée, which is generally done in Italian (as Medea), with extensive and very dramatic recitatives composed over fifty years later by Franz Lachner (to a German translation). The Lachner version, Italianized as usual, is what the Met used a few months ago, wonderfully sung and played. There are several audio recordings of that version featuring Maria Callas in the title role (one conducted by a youngish Leonard Bernstein), and even some video excerpts (the latter vividly conducted by Thomas Schippers).

Riccardo Muti recorded several other major works, but few of these have gained traction in the concert hall or opera house or in the non-specialist scholarly literature. Indeed, the only other Cherubini opera that one normally reads about is one that, like Médée, has spoken dialogue: Les Deux Journées (The Two Days, also known as The Water-Carrier). There are very contrasting recorded versions of it, including one conducted with loving care by Beecham and another starring Fritz Wunderlich. A spiffy period-style recording, released in 2001 and conducted by Christoph Spering, contains the musical numbers but not the spoken dialogue.

Cherubini’s all-sung operas (e.g., the fascinating Ali-Baba of 1833) have fared even worse. It was thus with special anticipation that this lover of French opera received the elegant “CD+book” of Cherubini’s 1813 opera Les Abencérages, ou l’Étendard de Grenade. This opera was composed for and performed at the Paris Opéra, where spoken dialogue was banned. Napoleon was in the audience at the premiere, and the work was quite a success, thanks to the dramatic and vocal skills of some remarkable singers, notably soprano Caroline Branchu (a “mulatto” or “quadroon”, in the language of the day — her grandmother was a freed slave on Saint-Domingue), tenor Louis Nourrit (whose son Adolphe would become the leading tenor of the Meyerbeer-Halévy era), and bass Henri-Etienne Dérivis (whose son Prosper would himself become a renowned bass).

The plot is set in Granada a few decades before its Arabic-speaking rulers (referred to in the opera as “the Moors”) were vanquished by the Spanish Christians. In accordance with historical reports (or legend), two tribes or clans, the Abencerrajes and the Zegris, are fighting each other, inadvertently hastening the final fall of Granada (the Moors’ last major holdout) to the Spanish crown in 1492.

Almanzor is preparing to wed the Abencerraje princess Noraïme, in the presence of a Spanish emissary: the warrior Gonzalve of Cordoba (a major historical figure; his name is more usually spelled today “Gonsalo”). Two Zegris — the vizier Alémar and the standard-bearer Octair — are keen to prevent this marriage, presumably because it would strengthen the hand of the Abencerrajes. The wedding preparations are interrupted by a battle that breaks out between Christians and Moors. The Moorish troops, under brave Almanzor, defeat the Spaniards, but, when the warrior returns to the city without the Moors’ treasured “standard” (i.e., battle-flag), he is sent into exile as punishment, and the Zegris now become rulers of Granada.

In the final act, Almanzor returns in disguise to meet with Noraïme (for a second love duet), and is captured by the ruling Zegris and condemned to death. Noraïme pleads to the Zegris to give him a chance to prove his innocence: let a champion represent him in combat against one of the Zegris. A masked warrior appears. (This age-old plot device would recur six years later in Scott’s Ivanhoe.) The unknown figure prevails against the Zegri warrior, reveals himself as Gonzalve, returns the missing standard, and informs everyone that the Zegris had perfidiously handed it over to the Spaniards in order to implicate Almanzor. The Spanish king sends word that peace will now reign in Castile. The vicious vizier Alémar will now be punished by the king and the interrupted wedding can resume. The good characters rejoice.

In the final act, Almanzor returns in disguise to meet with Noraïme (for a second love duet), and is captured by the ruling Zegris and condemned to death. Noraïme pleads to the Zegris to give him a chance to prove his innocence: let a champion represent him in combat against one of the Zegris. A masked warrior appears. (This age-old plot device would recur six years later in Scott’s Ivanhoe.) The unknown figure prevails against the Zegri warrior, reveals himself as Gonzalve, returns the missing standard, and informs everyone that the Zegris had perfidiously handed it over to the Spaniards in order to implicate Almanzor. The Spanish king sends word that peace will now reign in Castile. The vicious vizier Alémar will now be punished by the king and the interrupted wedding can resume. The good characters rejoice.

The musical numbers are all well-shaped and never outstay their welcome. Opera fans may know one fine solo scene already (“Suspendez à ces murs . . . J’ai vu disparaître l’espoir”), from an album by Roberta Alagna that was released by EMI in 2001 (French Arias) and then by DG in 2006 (as French Opera Arias).

There are numerous ceremonial intrusions (choruses and ballet numbers), as is often the case in French opera from Lully to Meyerbeer, Verdi, and Massenet. But I’m being unfair to call them intrusions. They are among the many jewels in the score, and this or that number would enhance any concert of excerpts from the world of opera.

There is no “Eastern” exoticism to be heard here, but we do get some Spanish local color: an orchestral set of variations on the famous tune “La Folia” and a troubadour number in bolero rhythm. (James Parakilas, in a chapter in Jonathan Bellman’s book The Exotic in Western Music, offers keen insights into the innovative power of the bolero rhythm ca.1800-20.)

This new recording is, for the first time, musically complete (except for some dance numbers in the last act) and sung in French by a mostly French-born cast. The Hungary-based Orfeo Orchestra uses period instruments that bring all kinds of fresh sonorities to the fore, especially because Cherubini included numerous solo passages for noted players in the Opéra orchestra (harpist Nadermann, hornist Duvernoy). Arias and ensembles are often underpinned by exciting rhythmic figuration and countermelodies in the strings. The Purcell Choir (likewise a Hungarian ensemble and likewise experienced in earlier repertoire) brings cleanness and zest to their many numbers. The choral writing includes a typically French sort of richness, with the tenor section split into two.

A 2022 concert performance of Les Abencérages featuring the performers on the Palazzetto Bru Zane recording. Photo: Emmanuel Andrieu

The singers all have a solid core to their tone and are totally secure up high: no wobbling or barking. A few have weak low notes, as is so often the case with singers nowadays. (On “the disappearing low end”, see Conrad L. Osborne’s recent book Opera As Opera, which I reviewed here.) They pronounce the French clearly and meaningfully, though Edgaras Montvidas (whose singing is beautifully secure and varied, as it was in Félicien David’s Herculanum) could use some coaching on vowels (e.g., é vs. ait). One can get a good sense of the high level of the performance from a trailer (filmed during a concert performance) or from the link I gave at the top of the review.

There were two previous recordings, neither widely available at the time but now to be found on some streaming sites. Giulini’s (1956), in good Italian, stars Anita Cerquetti, Alvino Mischiano, and Mario Petri; Peter Maag’s (1975), in (sometimes Italianate) French, features Margherita Rinaldi and Jacques Mars. Both recordings are worth visiting for their general professionalism, musicality, and dramatic alertness. But both are greatly trimmed.

All in all, this new recording is another major triumph for the Palazzetto Bru Zane’s Center for French Romantic Music, and a milestone in the gradual rediscovery of a major contemporary of Beethoven– one whom Beethoven rightly admired.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat different version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Les Abencérages, Luigi Cherubini, Orfeo Orchestra, Palazzetto Bru Zane