Opera Album Review: An Award-Winning Recording of a Spontini Opera Championed by Maria Callas

By Ralph P. Locke

Latvian soprano Marina Rebeka, under conductor Christophe Rousset, shows why Berlioz and others loved La Vestale.

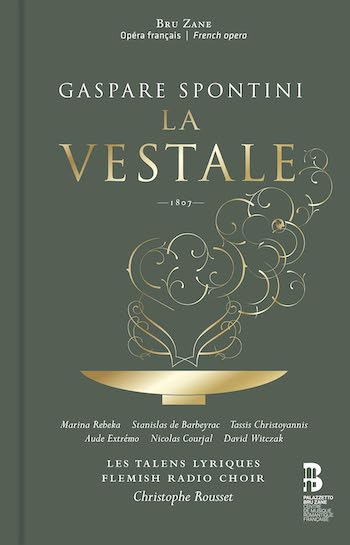

La Vestale, Gaspare Spontini

Marina Rebeka (Julia), Aude Extrémo (Vestal-in-Chief), Stanislas de Barbeyrac (Licinius), Tassis Christoyannis (Cinna), Nicolas Courjal (Supreme Pontiff), David Witczak (consul; also Haruspex chief).

Flemish Radio Choir, Les Talens Lyriques, cond. Christophe Rousset.

Bru Zane 1051 [2 CDs] 132 minutes

Gaspare Spontini (1774-1851) was one of the most prominent opera composers of the era between Gluck and Berlioz. I would say “between Mozart and Rossini,” except that his music sounds very little like that of either of those two composers, at least in his serious operas. (I reviewed here one of his many comic operas, the 1802 Le metamorfosi di Pasquale, and it sounds much more like “normal” operatic music of its era.) The music of his serious operas — including Olimpie (whose new recording I hailed here) and Fernand Cortez (whose first-ever complete recording, on DVD, has been much praised by others) — moves at a solemn and stately pace, focusing on dignified declamation of the text. Except, that is, when it is building frenetically through upward-surging melodic and harmonic sequences. More basically, the music tends to lack the dancelike lilt that helps create the joyous forward flow in the French and Italian operas (and instrumental works) of the Mozart-Cimarosa-Grétry era or that of Rossini and his emulators (e.g., Auber and Donizetti). And also the compactness of the writing (which relates him to Gluck): La Vestale (1807), which was his most famous work and has remained so ever since, fits onto two discs, whereas Rossini’s serious operas, with all their luxuriant coloratura, usually spread out onto three.

Gaspare Spontini (1774-1851) was one of the most prominent opera composers of the era between Gluck and Berlioz. I would say “between Mozart and Rossini,” except that his music sounds very little like that of either of those two composers, at least in his serious operas. (I reviewed here one of his many comic operas, the 1802 Le metamorfosi di Pasquale, and it sounds much more like “normal” operatic music of its era.) The music of his serious operas — including Olimpie (whose new recording I hailed here) and Fernand Cortez (whose first-ever complete recording, on DVD, has been much praised by others) — moves at a solemn and stately pace, focusing on dignified declamation of the text. Except, that is, when it is building frenetically through upward-surging melodic and harmonic sequences. More basically, the music tends to lack the dancelike lilt that helps create the joyous forward flow in the French and Italian operas (and instrumental works) of the Mozart-Cimarosa-Grétry era or that of Rossini and his emulators (e.g., Auber and Donizetti). And also the compactness of the writing (which relates him to Gluck): La Vestale (1807), which was his most famous work and has remained so ever since, fits onto two discs, whereas Rossini’s serious operas, with all their luxuriant coloratura, usually spread out onto three.

La Vestale (like his other serious operas) is remarkable for its almost architectural contrasts of simple materials. A phrase may repeat with slight variations, creating the effect of a coiled spring that makes the next harmonic move feel more urgently needed. Or, in one of the work’s several extended choral scenes, the women may sing a lyrical line punctuated by surly outbursts from the men. And, especially in the arias and duets, phrase lengths are often extended beyond a normative four bars to five, six, seven, or more, creating the sense of an individual holding forth in dignified and thoughtful manner about matters of high principle. Flashy coloratura singing is kept to a minimum, though there are many passages with two notes per syllable: in fast passages, this creates a sense of eloquent intensity (when sung well!).

In short, La Vestale sounds like nothing else in the standard operatic repertory, except, as I hinted, Gluck and Berlioz (to the extent that their operas have become “standard”). Listening to it in this splendid, gutsy, and elegant new recording, I can understand why Berlioz loved it so, and why the young Wagner was happy to conduct it (with the great Wilhelmine Schroeder-Devrient in the title role). Indeed, La Vestale seems pre-Wagnerian in its insistent avoidance of those entertaining (Brecht would call them “culinary”) aspects that endear so many operas of the years 1770-1850 to audiences.

I fear that I may be making this opera sound grim, partly because I haven’t mentioned the many moments that evoke a particular sort of scenic situation or musical style (e.g., pastoral style, complete with “horn fifths”; or the splendid little march for the vestal virgins in Act 1). But, in a performance as spirited and colorful as the one at hand, conducted by early-music specialist Christophe Rousset, La Vestale is continuously engaging and as fresh as a ripe pear from an orchard tree. It surely helps that the performers are using the 1993 Ricordi critical edition, though I would have appreciated a paragraph or two about any major differences between this and the scores previously used in performances and recordings (which often were done in Italian — the language in which the great Maria Callas sang the work).

The new recording won the Abbiati prize in 2023 for Best Opera Recording (presented by the organization of Italian music critics), and I easily see why. Rousset keeps the tempos moving, not overdoing the solemn atmosphere that might be thought appropriate to a plot about a vestal virgin in ancient Rome who has a love affair with a military general and, consumed by her passion for him, allows the flame in the Temple of Vesta to go out and must face official chastisement or worse. (No, she doesn’t end up being killed. In the end, the sacred flame is miraculously relit by a lightning bolt, signaling the wishes of the gods that Julia be spared and allowed to marry her hunky guy.) It also helps that the period instruments of Les Talens Lyriques make highly colorful and richly characterized sounds: a single popping bassoon line against a glittering harp, or a raspy warning from the entire brass section.

Concert performance of La Vestale. Conductor Christophe Rousset between Marina Rebeka (as the titular Vestal Virgin) in a light-blue dress, and Aude Extrémo (as the High Priestess) in dark blue. Photo: Gil Lefauconnier

The singing is almost continuously first-rate. La Vestale has most often been revived when there was a dramatic-lyric soprano able to handle its challenges, which prefigure those of, say, Bellini’s Norma. Callas made the priestess Julia one of her signature roles, and other singers whose abilities have enabled (indeed invited) it to be revived have included Rosa Ponselle, Leyla Gencer, Renata Scotto, and Raina Kabaivanska. Notable recordings, besides those with Callas, have featured Elena Nicolai, Rosalind Plowright, and Karen Huffstodt (the last of these conducted by Riccardo Muti). YouTube currently offers a complete recording (not video), conducted by Bertrand de Billy and featuring Elsa van den Heever (well known to Met audiences and PBS viewers) and a perfect tenor for the role of Licinius: Michael Spyres.

Here, in the title role of the virgin priestess Julia, we have Marina Rebeka (from Latvia, with additional training in Italy), who proves herself a worthy successor to Callas and the others. She immediately captivated this listener through some of the most assured legato singing I have encountered in years. I was reminded of several great lyric sopranos early in their careers, such as Monserrat Caballé, Katia Ricciarelli, and Cecilia Gasdia. Rebeka is now married to a sound engineer, and together they have released recordings featuring her on their own label, Prima Classic. I will be on the lookout for those!

The role of Julia’s beloved soldier, Licinius, is extremely well taken by tenor Stanislas de Barbeyrac, whose singing and acting-through-singing I already admired greatly in a recording (on this same label: Bru Zane) of Offenbach’s La Périchole.

Equally confident and communicative is mezzo Aude Extrémo, whose voice is solid and full from very low to very high. I have admired her previously in the La Périchole recording that I just mentioned and in a concert performance (on YouTube) of Félicien David’s stirring and melodious grand opera Herculanum.

Tassis Christoyannis adds another leaf to his laurels as the hero’s confidant, Cinna; his voice has the firm high notes that this “baritenor” role requires, though it seems less than ideally full, something I’ve never noticed in his wonderful recordings of French art songs. To his credit, he never forces, barks, or woofs.

The major weak link is the Supreme Pontiff, Nicholas Courjal, whose dry and wobbly sounds I have objected to in several recordings, including as Bertram in Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable. He does convey a certain authority, thanks to clear enunciation. But the role was created by one of the great singing basses of the age, Henri-Etienne Dérivis, and you’ll have to turn to some other recording (perhaps a noncommercial one) to hear it sung with proper authority and dignified beauty. David Witczak, another bass-baritone, is capable in two small roles.

The recording was made in a Paris studio, and is miked (or are we now supposed to spell it “miced”?) with great sensitivity. The accompanying book contains a short but first-rate historical essay by Alexandre Dratwicki, the librettist Dujouy’s preface, an insightful 1807 review by a critic known as “Amar,” an appreciative 1845 essay by Berlioz, and the libretto — all in French and Charles Johnston’s good (if sometimes a bit literal) English. Plus wonderfully evocative set and costume illustrations. To get a taste of what is on offer, YouTube offers a two-minute trailer and a four-minute commentary by conductor Rousset.

Oh, if you want to hear the work turned into Leoncavallo-like verismo, listen to any passage of Licinius’s role sung — with magnificent but mostly unvaried vocal technique — by Franco Corelli (in the 1954 Italian-language recording with Callas).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.