Book Reviews: A Provocative Trio of Volumes on Architecture and Landscape Architecture

By Mark Favermann

In very different ways and on very different topics, three recent books assuage notions that architecture/design books are formidable reads.

Architecture and design books usually have a few things in common: they often are high-priced (due to lavish illustrations and limited audience appeal); they are often densely written because most architects and designers are visual rather than verbal; and they are often deadly earnest because they are very serious especially about their work. In very different ways and on very different topics, three recent books assuage notions that architecture/design books are formidable reads.

Seeing Trees: A History of Street Trees in New York City and Berlin by Sonja Dümpelmann. Yale University Press, 336 pages, $50.

This fascinating and well-illustrated study by Sonja Dümpelmann, an associate professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, examines what urban street trees tell us about humanity’s changing relationship to nature and the built environment. Seeing Trees reflects considerable empirical research and it translates this empirical date into a compelling narrative about the intersections among nature, time, and space. Dümpelmann discusses the various roles trees serve in the urban environment, looking at them as major strategic pieces placed in the streetscape, a meeting place between social history and the environment. Over time, trees have been regarded as industrial waste sanitizers, civic beautifiers, nuisances, urban climate enhancers, neighborhood landmarks, and a means to soften a hard landscape.

Dümpelmann brings an accessible writing style and admirable curiosity to the task, exploring how trees serve as both symbols and observation points for an in-depth interpretation of the complexities of urbanism, past and present. She notes how New York City and Berlin initially began to systematically plant trees to ameliorate the negative aspects of the polluted urban environment during the nineteenth century. But Dümpelmann‘s voice, authoritative and original, places this straightforward impulse for civic ‘improvement’ into larger social, cultural, and political contexts. By so doing, she extends the boundaries of landscape history; she cleverly blends together examinations of arboriculture, landscape design, and urban planning. Seeing Trees will serve as an important reference point for urban and landscape history in the future.

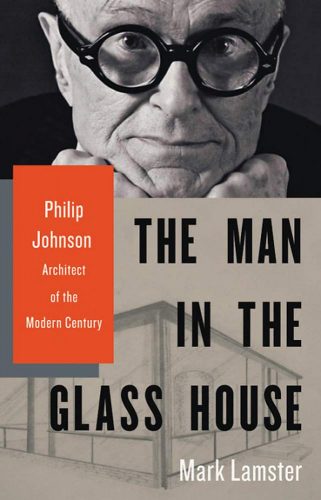

The Man in the Glass House by Mark Lamster. Little, Brown, 508 pages, $35.

A biography of the bitchy showboat doyen of international architecture and design, Philip Johnson, a snarky, snobby, hypocritical, sycophantic, well-connected, very long-lived (98), independently wealthy (Alcoa Aluminum), provocative, aesthetically uneven, and not really likable former Nazi sympathizer. The author, the architecture critic of The Dallas Morning News, righteously calls Johnson’s many professional misses and very few hits.

A particularly relevant fact: Donald Trump was one of Johnson’s last major clients, for whom he designed some rather mediocre edifices. Lamster sees this as representative behavior of a man “glad to perpetuate his image as an architectural enfant terrible by association with New York’s most craven developer.” However, Johnson was actually much more than this.

He was founding director of the Museum of Modern Art’s architecture department and co-author of the influential 1932 book The International Style. This was the catalogue for the legendary MoMA show that introduced America to progressive modern European architects such as Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Walter Gropius. Born to an upper middle class famiy, Johnson traveled from the lap of luxury in Cleveland, Ohio, to a permanent table at the Four Seasons restaurant (which he designed).

Correctly, Lamster accuses him of being a “would-be American Hitler, and an American agent of Nazi Germany,” and makes his case for this corrupt behavior clearly. In the ’30s, Johnson was a founding member of a Nazi front group called the American Fellowship Forum, whose magazine explored such questions as “Can the Jewish Problem Be Solved?” Often visiting Germany, he wrote and broadcast in favor of fascism for years — a Nazi by any other name, etc. The beginning of WWII finally shut him up. It is hard to believe that a career could recover from these despicable activities, but somehow Johnson’s did. He apologized for his Hitler-friendly actions later in life — that is, when he seemed to remember them.

In his 40s, Johnson emerged from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design in 1943 as a slavish Mies van der Rohe acolyte. Perhaps Johnson’s most famous work, his New Canaan, Conn., Glass House (1949), was an iteration of van der Rohe’s projects: The 1929 Barcelona Pavilion and The Farnsworth House (1951), well promoted but then under construction. Though most of Johnson’s architectural projects were uneven and unoriginal, in 1979 he became the inaugural winner of architecture’s highest award, the Pritzker Prize.

For some reason, Boston became a dumping ground for Johnson’s worst designs: the oddly formed One International Place; the boring, postmodernist assemblage at 500 Boylston Street; and Johnson’s hideous, uninspired expansion of the legendary McKim, Mead & White Boston Public Library. Recently opened up to entrance from the street, his Brutalist design originally called for no windows and no interior artwork.

Still, Lamster correctly credits Johnson for his good work. The 1934 MoMA show Machine Art was a major curatorial milestone because it highlighted how everyday objects were aesthetic acts of design, including an airplane propeller, a perfume bottle, a ball bearing, etc. “It redefined which materials might and might not be suitable for display in the context of an art museum and dramatically elevated the status of industrial design.” Lamster considers MoMA’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden an example of great work as well as the plaza outside Lincoln Center. He also praises Johnson’s unusual art gallery at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C.

Lamster conclues that “(Johnson) was a gay man with a fascist history living in a glass house, and he liked nothing better than to throw stones.” Trite — but somehow just right.

Cocktails and Conversations, Dialogues on Architectural Design by Abby Suckle & William Singer, Co-chairs, AIANY Architecture Dialogue Committee. Published by American Institute of Architects New York Chapter, 184 pages, $25.

A compilation of dialogues on architectural design, this book makes a convincing case that architects and what they do can be very human — and even enjoyable.

According to architect Abby Suckle, “One Friday night about six years ago, we found ourselves standing in the Center for Architecture’s Tafel Hall sipping white wine from plastic tumblers. We remarked that it was amazing that every cultural institution of significance in New York City seemed to have a fun Friday evening event involving drinks while, sadly, the lights at the Center for Architecture were turned off. Everyone standing around commiserated with us. We suggested that architects are fun and like to talk about design — and they like to drink. Would it be possible to pair an architect with a journalist and have a bartender create a drink in the spirit of the architect’s work?”

Thus, Cocktails and Conversations was born. “We proceeded to invite architects and landscape architects to share their ideas about design with an audience. We paired them with people who “read” the built environment: journalists and critics who distill and explain it to us; historians who frame it in time; and clients who commission it. The programs have been provocative, inspiring, and lively—and definitely fun.” These gatherings are a hoot — I have attended.

During the Cocktails and Conversations series, some of today’s most interesting and provocative design practitioners have discussed what informs their designs. They have shared insights about how to create form, how to relate new to old, what they have learned from their built projects and ones still to be realized. They have talked about designing at all scales, from the macro to the micro, the role of drawing, dishing about clients, politics, and the economy along with exploring issues of aesthetics, color, and form. Paired with journalists, curators, historians, critics, educators, and clients — those who create narratives that frame the intellectual discourse about the built environment — the conversations focused on the issues that are the most pertinent that face the design professions today.

To (literally) lubricate the discussion, master mixologists invented cocktails in the spirit of each designer’s work. The recipes are included in the Cocktails and Conversations volume, which succeeds at its aim — to inspire and delight. Cleverly illustrated, the book collects a wonderful series of statements from the practitioners, sentiments that underscore the joy, humanity, creativity, and impact of the built environment.

An urban designer and public artist, Mark Favermann has been deeply involved in branding, enhancing, and making more accessible parts of cities, sports venues, and key institutions. Also an award-winning public artist, he creates functional public art as civic design. Mark created the Looks of the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games in Atlanta, the 1999 Ryder Cup Matches in Brookline, MA, and the 2000 NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. The designer of the renovated Coolidge Corner Theatre, he is design consultant to the Massachusetts Downtown Initiative Program. Since 2002, Mark has been a design consultant to the Red Sox. Mark is Associate Editor of Arts Fuse.