Book Review: Anne Frank’s Diary — The Graphic Version

By Helen Epstein

I’m impressed with the new adaptation and depressed that it’s considered necessary.

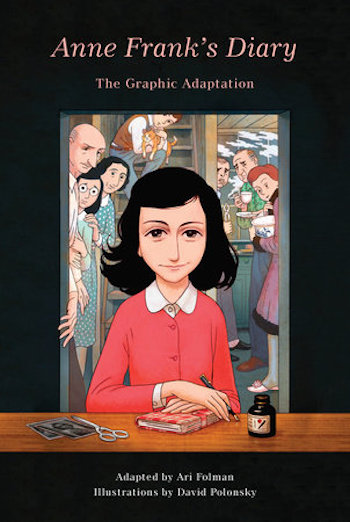

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation. Adapted by Ari Folman; Illustrations by David Polonsky, Pantheon 149 pp.

When the Anne Frank Fonds in Basel, owners of the world rights to Anne Frank’s diary, contracted with writer Ari Folman and illustrator David Polonsky to adapt and animate the classic text in 2013, they were responding to a dramatic change in young people’s reading habits worldwide. Four years later, according to Publisher’s Weekly, graphic novels (a category that includes memoir and other non-fiction) accounted for over $1 billion in sales in North America, driven largely by children and school librarians. In Japan, the graphic form of manga has long been gaining ground, and in Europe, where such classics as The Adventures of Tintin and Asterix have for decades been published in hardcover, the graphic novel form is part of the mainstream. Computer-animated films are inspiring popular cross-over books and the copyright holders of The Diary of Anne Frank — a staple of school curricula and one in which a girl features as both author and heroine — were worried about keeping up with the times. Folman had noticed the change in reading habits of his own children, but when asked to adapt the diary, he hesitated.

“The text is iconic,” he writes in the Adaptor’s Note. “How could I ‘edit’ the book?” he writes. “If we were to illustrate the entire text in a graphic edition it would require the better part of a decade and likely be 3,500 pages long. The trickiest task, then, would be to retain only a portion of Anne’s original diary while still being faithful to the entire work.”

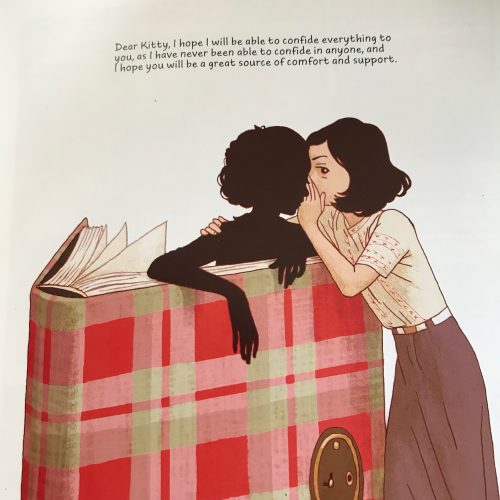

A tricky task indeed and one that many readers would argue is unnecessary. The diary is probably the most celebrated book ever written by a teenage girl, a sacred text for some, and a teaching tool that illustrates the end result of racism. Its appeal lies in Anne’s intimate account of coming of age in the close quarters of a secret annex in Amsterdam during the Nazi occupation of Holland. Several surviving photographs attest to Anne’s vivacity just before she turned 13 and made her first diary entry on June 12, 1942: “I hope I will be able to confide everything to you, as I have never been able to confide in anyone, and I hope you will be a great source of comfort and support.”

Three weeks later, Anne’s older sister Margot received an official summons to report to a Nazi work camp. Having prudently fled rising Nazism in Germany in 1933, Otto Frank took the summons as a sign to go into hiding in Holland. He chose the secret annex of the building where he ran a business producing Opekta, a pectin used to make jam. His small group of loyal Dutch employees agreed to keep the office and warehouse running and to provide the Franks with food and supplies as they hid from the Nazis.

For nearly two years, Anne wrote entries in the diary she named Kitty and in various notebooks, until, in March of 1944, she heard a radio broadcast by a minister of the Dutch government-in-exile calling on citizens to document life under the Nazi occupation. Her diary suddenly took on an historical value, and Anne decided to write a second draft. Using loose sheets of paper, she cut and added material, invented pseudonyms for the four non-family members in hiding, and standardized her entries. What we call “the Diary” is actually a memoir, whose final entry is dated August 1, 1944. Three days later, the hiding place was raided by the Gestapo and its occupants arrested. Anne was deported to a series of camps: Westerbork, Auschwitz, then Bergen Belsen, where she died. Otto Frank’s secretary Miep Gies was able to salvage Anne’s papers.

In 1945, Otto Frank returned to Amsterdam and learned that his wife and two daughters were dead. When he was given Anne’s “diary documents,” he could not, at first, bear to read them. Then, he translated them into German for surviving friends and family, who encouraged him to publish her writing. After finding a publisher, he redrafted Anne’s manuscript, cutting out some material that he and/or the publisher considered inappropriate for a series aimed at young people in 1947 — about sex, complaints about her mother — and reinserted some she had cut.

“Dear Kitty,” Anne had written a month before her 15th birthday, “You’ve known for a long time that my greatest wish is to be a journalist, and later on, a famous writer. We’ll have to wait and see if these grand illusions (or delusions!) will ever come true, but up to now I’ve had no lack of topics. In any case, after the war I’d like to publish a book called The Secret Annex. It remains to be seen whether I’ll succeed.”

Thanks to her father and many journalists, editors, and other writers, Anne succeeded beyond her wildest expectations. Het Achterhuis, literally “the house behind” or The Secret Annex, was published in Dutch in 1947, then in French and German translation in 1950, Two years later, it was published in English (with a one-and-a-half page introduction by Eleanor Roosevelt) as The Diary of a Young Girl. Sales took off, schools began adopting it as a text, and theater and film adaptations followed. The Broadway play won a Pulitzer for Best Drama and the Hollywood film garnered three Oscars.

Each translation and adaptation altered Anne’s text. Some changes were subtle and affected only one edition, such as the softening of adjectives Anne used to describe Germans — for German readers. Other changes were sweeping, such as deliberately cutting out references to Anne’s Jewish identity, and making her “universal,” or what today might be called “more relatable” to readers. The most famous edit of the diary was lifting one of Anne’s sentences out of context and making it a feel-good ending to her story: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.”

Google “Anne Frank” today and you get 23,000,000 hits.

The Anne Frank Museum in Amsterdam, located in the building that housed the secret annex, has a staff of one hundred, and receives over one million visitors per year. According to their website, adaptations of The Secret Annex have been translated into 70 languages and read by more than 30 million readers. There are condensed children’s, young adult, and school editions. There is a “definitive” edition by Mirjam Pressler that combines Anne’s two versions with her father’s and contains 30 percent more material. There is an authorized graphic biography of Anne; an authorized play that is performed by hundreds of professional theaters and school groups every year, as well as an “underground” script (see Meyer Levin’s book Obsession) that is legally proscribed from performance. There are countless scholarly works about the diary, biographies of the protagonists, and many Anne Frank-inspired works of literary and visual art by a wide variety of artists. Critics and scholars, for their part, have long debated the issues of adaptation and appropriation.

Because the diary and its adaptations have received global attention and respect, Holocaust revisionists and deniers have called it, and continue to call it, a fraud. To refute these charges, the Netherlands State Institute for War Documentation in Amsterdam ordered a thorough investigation of the documents and, in 1986, published a “critical edition,” attesting to the authenticity of Anne’s handwriting and writing materials, providing articles on the background of the Frank family, and the circumstances surrounding their arrest and deportation.

In 1997, prompted by the publication of two more scholarly books about the dairy, Cynthia Ozick wrote a scorching essay titled The Misuse of Anne Frank’s Diary.

“A story may not be said to be a story if the end is missing,” she wrote. In addition to being distorted by what happened after Anne’s arrest, the text had been “bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, traduced, reduced; it has been infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized; falsified, kitschified, and, in fact, blatantly and arrogantly denied. Among the falsifiers have been dramatists and directors, translators and litigators, Anne Frank’s own father, and even — or especially — the public, both readers and theatregoers, all over the world. Almost every hand that has approached the diary with the well-meaning intention of publicizing it has contributed to the subversion of history.”

I shudder to think what she would write about this well-meaning endeavor. Ari Folman is best-known for writing and directing the animated documentary Waltz With Bashir, an extraordinary combat memoir inspired by his experiences as a 19-year-old soldier in the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon. He was in one of the units that provided cover to right-wing Lebanese Christian militias that murdered Palestinians in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. He subsequently found he had blocked out all memory of being there. Waltz combined years of interviews with his fellow soldiers, dreams, fantasies, and photojournalism as Folman tried to reconstruct his participation in a massacre he had repressed. Like Art Spiegelman, whose Holocaust-themed graphic novels Maus brought adult comics into the international mainstream, Folman is another son of Holocaust survivors committed to documenting history.

At the end of his film Waltz with Bashir, animation gave way to actual video footage. Folman later told interviewers that he wanted to make clear it was not just “a cool anti-war movie with great drawings and music. I wanted to put it very clearly that this massacre happened — more than 3,000 people were slaughtered and most of them were kids, women, old people. That video footage puts my story in place, the design and animation style in place, the story in place, and the audience in place.” His film of Anne’s diary, unlike the book, Folman has said, would include Anne’s deportation and death in a Nazi concentration camp.

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation is 149 pages long — a little more than half the length of the original — and fewer than ten of those pages are predominantly text. Its hard black cover — many graphic novels are published without a jacket — frames a dramatic full-color portrait of Anne at her desk with fountain pen and ink as the other seven occupants of the secret annex peer out from behind her.

A page titled “Cast of Characters” provides colorful mini-portraits of the four Frank family members, their four annex-mates, and their six protectors, vividly rendered by David Polonsky, his artistic partner on Waltz and an illustrator of Israeli children’s books. Dates are sometimes noted at the top left of the hospital white pages (“Friday, June 12- Saturday, June 20,1942”), sometimes not. Small pieces of Anne’s narration appear in rectangular text captions at the top of panels: sometimes they are cherry-picked from her diary, sometimes out of order, sometimes not; sometimes they are paraphrased; sometimes invented.

Folman has also invented dialogue between the main characters (“I’m telling you, Anne will get us all captured.” “I agree her behavior is out of control.” “Oh, stop being so hard on her”). The mashup of terms from the 21st century and the 1940s is not likely to be noticed by a young reader, but I found it jarring. I also found myself not knowing where to focus: the text in the speech balloons often competes for attention with the narration in the captions. Ultimately I found myself following the illustrations rather than the words.

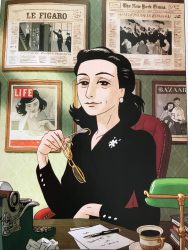

Polonsky’s illustrations (many based on photographs of the protagonists) are the most original and interesting feature of this graphic novel. Unconstrained by the demands of realistic stage or film conventions and building on his prior collaboration with Folman, Polonsky freely translates basic information as well as thoughts, dreams, fears and fantasies into a wide variety of images drawn from fine art, book and magazine illustration, period photos, posters, and postcards — all of which he does, for the most part, brilliantly.

When Mr. van Daan informs the Franks of the three major rumors circulating about their sudden disappearance, for example, Polonsky draws three scenarios: first, the family in single file on skis before a Swiss Bank against a backdrop of the snowy Alps; second, the family on bicycles in the flat Dutch countryside, a windmill behind them; third, a dark panel of the family crammed into a military vehicle in the middle of the night. When Anne claims that she doesn’t care if her mother dies, Polonsky provides an illustration of the Franks at Edith’s newly-covered grave with a rabbi intoning Kaddish and Anne pointedly not mourning. When she writes, “I’ve made up my mind to lead a different life from other girls,” Polonsky draws her as a chic, mature young author with a wall of framed front pages of Le Figaro, New York Times, Life, and Bazaar behind her, all featuring her diary.

The collaborators have taken pains to emphasize the particularity of Anne’s story. The text makes clear that Hitler sought to exterminate Jews; Polonsky provides panels featuring the yellow star Jews were required to display on their clothing and illustrates comments from strangers. A helmeted soldiers notes “These Jews… never warm enough for them,” and an actress on a theater poster declares “I don’t perform for Jewish swine!”

Many readers — especially women — think it a travesty to see Anne’s diary interpreted by a couple of middle-aged men. When I read through the 1952 Modern Library edition cover to cover — which I hadn’t done since my teens — I was struck by the integrity and continuity of Anne’s voice and the staying power of her narrative. Why not leave a classic alone? Why not excerpt a chunk for students who think it’s too much work to read the entire diary? Wouldn’t a part of the original writing where they could imagine the author be better than a graphic adaptation?

Apparently not for the current crop of teen and tween readers. I listen to friends, parents, teachers, and librarians argue that Anne’s diary, like everything else, needs to be adapted to more visually-driven times. Anne’s earnestness, humor, anxiety, teen crazes, loves and hatreds are all there to be discovered but what good is that unless her diary is read? Even I have to confess that, after browsing Folman and Polonsky’s vivid adaptation over a week, the 1952 edition looked like a sea of words.

I’m impressed with the new adaptation and depressed that it’s considered necessary. I hope that the Anne Frank Fonds made a good bet and, to borrow from an idea from D.W. Winnicott (as portrayed in Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Are You My Mother?) that this is a “good-enough” Anne Frank for 2019.

Helen Epstein is the author of the Holocaust-related trilogy of memoirs that ends with The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma. She has reviewed for artsfuse.org since its inception.

Tagged: Anne Frank's Diary: The Graphic Adaptation, Ari-Folman, David Polansky, graphic novel