Book Review: Reading Literature Behind Bars

Mikita Brottman gets raw, often very funny, and unexpected responses to the masterpieces she puts before her prisoners.

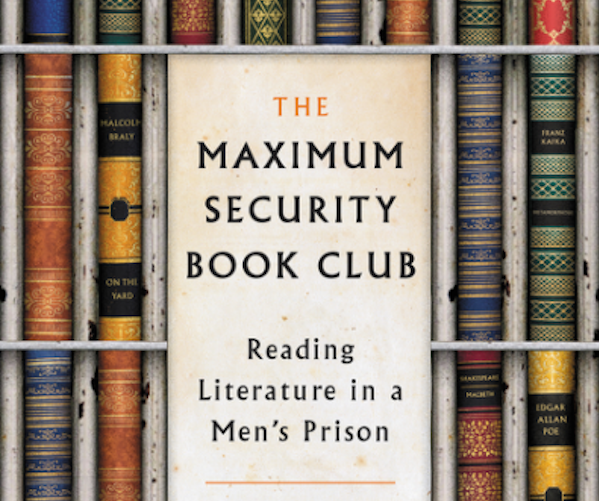

The Maximum Security Book Club by Mikita Brottman. (Harper, 272 pages, $26.99)

By Gerald Peary

From the beginning of her exquisite, engrossing memoir, The Maximum Security Book Club, author Mikita Brottman makes clear that she is no social worker or altruist, when offering a “Great Books” literature course to nine male prisoners at Jessup Correctional Institute (JCI) on the outskirts of Baltimore. “I can’t claim a higher motive, a belief in literature as redemptive,” she explains. “I certainly don’t see reading as an antidote to unlawful behavior.” Her objective is far more modest. “… I saw the book club mainly as a way for me to share my love for the books that have come to mean the most to me.”

Also, the compulsively honest writer admits, conducting this volunteer class is honey to her ego. In her employed life, Brottman is a Maryland college professor suffering the alienation of today’s academics, so often out of touch with their tweeting/texting students. Happily for her teaching, there are no cell-phones allowed at maximum security JCI. There are lines of prisoners begging to get into her class. Brottman writes, “It’s enormously gratifying to be with men who … tell me my visit is the highlight of their week …” She adds, “It’s definitely a boost to my self-esteem to know how important I am to the prisoners, when these days my college students don’t even seem to know my name.”

So what books should she teach, cognizant that many of the prisoners are dropouts from school, barely educated in traditional terms? Perhaps foolishly, Brottman starts up her book club–there are no grades or exams, though often homework—with two unmistakably difficult texts, Heart of Darkness and Bartleby, the Scrivener. Maybe the prisoners will get into these classics because they are fairly short?

Brottman recalls that Heart of Darkness even eluded her when a literature student at Oxford. No surprise then, her class at JCI are perplexed to a man trying to grasp Conrad, with those laborious stretched sentences that contain so much vocabulary that’s beyond them. One of her students tells her he’d taken another class in the prison where the teacher had said, “A good writer gets to the point.” When Brottman reads aloud of Kurtz, “His soul was mad….Being alone in the wilderness,” one of the men agrees, “That’s what happens to guys in lockup.” As for the cannibalism, a prisoner, Kevin, chimes in, “We had a cannibal here once. Any of you remember Tiny?…He’d been eating those hookers he killed.”

The prime way Brottman’s nine convicts relate to Heart of Darkness, and to every other book, is by moving quickly from what’s on the page and free associating about their own lives, both in and out of prison. Many teachers would be delighted that their assignments were taken in such immediate and “relevant” ways. For most of her book, Brottman is annoyed by her students for being so solipsistic. She is an aesthete above all, frustrated that her class can’t get into literature as literature. Without saying it, Brottman wishes her convicts to be New Critics behind bars, burrowing with blinders into the multi-layered texts.

Instead, she gets raw, often very funny, and unexpected responses to the masterpieces she puts before her prisoners. (Brottman refuses to use the word “inmates,” as those incarcerated consider it a euphemism invented by their jailers.)

“3 out of 10” is one verdict on Heart of Darkness. The horror! Melville’s narrator for Bartleby, the Scrivener is dismissed as a wimp boss for not making Bartleby get down to work, “for letting his employee walk all over him.” Nobody gets excited about Bartleby, “that guy with the weird name,” and I gather nobody is stirred by Melville’s immortal “I’d prefer not to.” Some of the convicts, however, prefer not to read the novella back in their cells because a Baltimore Ravens football game is on TV.

Eventually, Brottman assigns an easy book for her class, Charles Bukowski’s Ham and Rye. They like it! They appreciate Bukowski’s street-wise protagonist, Henry Chinoski. Can a teacher learn from one’s students? Brottman lectures that the book stretches credibility when Henry’s father beats him with a razor strap because, mowing the grass, Henry missed one blade. Says Brottman, “The men disagreed vociferously, recounting similar sadistic tasks set by their own fathers and the violent punishments imposed when they failed. They all seemed to have fathers as violent as Henry’s.”

In the middle of her course, Brottman gives in to the call for relevancy in the classroom, asking her students to read Malcolm Braly’s prison novel, On the Yard. It’s a popular choice for most. And it’s got cursing, including the word “cunt.” But what of William Burrough’s Junkie? Surely, everyone can get into this wry tale of drugs and thievery? Its a bad day for teacher Brottman; everyone revolts when they learn that Burroughs was queer. As for Macbeth, reading Shakespeare aloud is a thorny task. “It’s so boring,” says one student and, another dire day for Brottman, practically the whole group snoozes in their seats when Brottman shows them the Roman Polanski movie on DVD.

And yet, more than occasionally there’s a breakthrough, someone being incredibly bright and insightful in his own inimitable way. For example, one student articulates a surprising respect for the murderous Macbeth: “He take it the whole way through, fuck it. Even when they kill him at the end, his name still gonna ring.”

The brightest time for the JCI class is their impassioned battle with their instructor over Lolita. Brottman is an avowedly non-political teacher and critic, seemingly disinterested in questions of race, class, gender, attracted to existential quandaries, to the non-puritan, the uncanny, the transgressive. So she sees no issue in her possessing “an immense sympathy for Humbert Humbert … I’ve always had a weakness for eloquent gentlemen.” Nor in regarding Nabokov’s tale of a middle-aged man having sex with a kidnapped under-aged girl as a touching love story.

Her class challenges her as if they were feminist activists. Where Brottman sees in Humbert Humbert an amazingly articulate poetic soul, they find only a hideous pedophile. A scammer all the way. Someone whom they would kill to keep away from their own kids. One prisoner speaks for all regarding Nabokov’s much-beloved protagonist: “It’s all bullshit, all his long fancy words. I can see through it. It’s all a cover-up. I know what he wants to do with her.”

A petulant Brottman fights back, arguing, “Can’t we manage to have a discussion of Lolita without using the word pedophile?” Nope. Her students won’t budge on this one. Riding home afterward to Baltimore, she gets hopelessly stuck in traffic. “As I sat in my car waiting for things to move again, I had to face the fact that, much to my dismay, the prisoners had got it right. These men, some of whom were guilty of terrible crimes, immediately sympathized with twelve-year-old Lolita. They recognized at once that she was suffering.”

It’s a remarkable epiphanic moment in Mikita Brottman’s fine book, when she admits to herself that Nabokov’s dazzling writing has deceived her. More, she credits her barely educated convict students for opening up her head and heart.She has read the novel often. For the first time, she is privy to “the main fact of the matter: Lolita’s pain.”

Gerald Peary is a retired film studies professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.