Book Interview: A New Take on Kafka — A Conversation with Peter Wortsman

“The standard view of Kafka reduces him to the patron saint of neurotics … my selection highlights his considerable strength in enduring imagined torments that prefigured actual calamities to come.”

By Bill Marx

Three versions, in English, of the opening line of Franz Kafka’s celebrated story “The Metamorphosis” (or “The Transformation”): “When Gregor Samsa woke one morning from troubled dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous insect.” (Malcolm Pasley); “One morning, upon awakening from agitated dreams, Gregor Samsa found himself, in his bed, transformed into a monstrous vermin.” (Joachim Neugroschel); “As Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed into some kind of monstrous vermin.” (Joyce Crick). The Crick sentence refers you to a feisty ‘explanatory note’: “Kafka’s word ‘Ungeziefer’ suggests a ‘pest’ or ‘vermin,’ but no specific creature. The details of Gregor’s body do not correspond to any insect, and do not cohere: if his belly is so domed how do his small legs reach the ground?” So much for those benighted translators who make poor Gregor wake up as a bug.

There have been, by my modest count, well over two dozen renditions of this story into English and just about as many translations of his other short fiction. A new collection of Kafka translations would not seem to be all that noteworthy: the insect versus vermin fracas has lost considerable pizazz. But not only does the excellence of the translations in Peter Wortsman’s Konundrum: Selected Prose of Franz Kafka (Archipelago Books, 383 pages, $18) delight, but he wisely decided to mix-and-match a number of Kafka’s texts, fiction and non-fiction. Not only are the oft-printed stories (“In the Penal Colony,” “The Hunger Artist”) here, but diary entires, parables, and excepts from letters. The result is a distinctive vision of the writer — not the “patron saint of neurotics” beloved by the 20th century, but a black comic absurdist who seems particularly apt for the 21st century.

I sent some questions by way of e-mail to Wortsman, asking how he made his selections, inquiring about the difficulties of translating Kafka today, and wondering which was his favorite tale in the collection. It turned out to be mine as well — a razor sharp version of the sardonic “A Report to an Academy,” in which an ape, in order to escape captivity, masquerades (successfully?) as a human.

Arts Fuse: Why have there been so many translations of Kafka? What is the value of multiple versions of his tales and novels?

Wortsman: I hope you and your readers will not find it disingenuous if I respond to your first question with a question. Why have there been so many dramatic takes on the scripts of Shakespeare and Beckett and so many interpretations of the musical scores of Mozart and Bach? Wasn’t it enough that Sir Laurence Olivier, Sir John Gielgud, Jonathan Pryce, Angela Winkler, to name only a few modern interpreters, inhabited the role of Hamlet? Did French director Roger Blin’s stage debut of En Attendant Godot disqualify Peter Hall’s English language follow-up, or subsequent stabs at portraying Beckett’s characters by Zero Mostel, Austin Pendleton, Joseph Chaikin, Bill Irwin and prisoners at San Quentin? Did Wanda Landowska’s and Glen Gould’s fingers forever drain the Goldberg Variations of future interpretive possibilities?

I think not. A translator worth his or her salt is not all that dissimilar from an actor or an instrumentalist, except that the fiddling with language is done in private. The translator takes a track lay down by an author in another tongue, in another time and place, and channels its essence for his contemporaries.

As in everything worth doing, there is of course also a selfish end. For a translator engaged with the German tradition, to tickle clear English out of Kafka’s enigmatic texts is one of the most formidable challenges and greatest delights of the craft. I will, furthermore, hazard an assertion likely to make some readers bristle. Interpreting Kafka for a translator is somehow akin to portraying Hitler for a German actor? That is not to suggest that Hitler’s crude ranting bears the slightest resemblance to Kafka’s profoundly subtle and painfully lucid prose, but rather that both personae are inscribed as extreme points of reference and sounding boards of the German unconscious, continuing to touch us, for better and for worse, to prod our curiosity and prick our conscience long after their deaths. Both tap the dark mythic dimension of the German mindset dangling in universal dread.

AF: What are the challenges of translating Kafka? Have they increased over the years, the further away we are from his era? There are critics who argue that the closer a translation is in time to the original publication the better it is.

Translator and writer Peter Wortsman. Photo: Jean-Luc Fievet.

Wortsman: Kafka formulates the ineffable in precise, unambiguous sentences that test the limits of language. Furthermore, underlying his every utterance in narratives long and short, letters and journal notations, there is a hint of humor always kept in check, always threatening to erupt at the most inopportune moment. To capture and evoke that tender balance demands a Zen-like concentration. If I had to seek a fair approximation of a face to characterize Kafka’s prose, I’d pick Buster Keaton’s deadpan expression. A silent short leaps to mind in which, playing a desperate miner, Keaton takes up pick and shovel to dig an actual hole and ends up literally digging the proverbial hole to China. Any other comic would have stopped there. But Keaton takes it to the limit and beyond, emerging after an implied time lapse dressed as a Mandarin, with his Chinese wife and little half-Caucasian, half-Chinese offspring in tow. My late aunt, Dr. Stefanie Isser, a doctor of law, once heard Kafka read in Vienna. An eminently rational thinker, she could not make head or tail of the odd individual and his peculiar tales. “What was he like?” I pressed. “Well,” she hazarded, “he trembled in the telling, straining to keep from laughing.” The greatest challenge in evoking Kafka’s actuarial accounting of the unthinkable is to capture that squelched mirth on the edge of hilarity.

As to your second question regarding the time lapse between translation and writing, I can only speak of the here and now I know. Having first come upon his words in high school and then encountered them again in college, in the Muirs’ British English translation, and later nosed my way through his notebooks and letters in the original German, Kafka framed my literary consciousness as the longest lasting model and influence; I have aged while the tales have remained timeless. Translations closer in time to the original evoke the immediacy of their first reception, but later translations render subsequent immediacies no less valid. Whether by years, centuries, or in the case of ancient texts like The Epic of Gilgamesh, by millennia, the reader is in any case far removed from the moment of writing. Every translation serves as a shaky suspension bridge of sorts, spanning the eternity between conception and perception.

AF: Among your many translations from the German, you have published Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm and Tales of the German Imagination: From the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann. How did translating tales of the fantastic inform how you translated and understand Kafka?

Wortsman: Kafka has long been for me (and for us) a bellwether of sorts. As I wrote in my afterword to this new selection and translation, “his name was consecrated as a proper adjective, Kafkaesque, synonymous with the nightmarish, the ominous, and the bureaucratically bizarre, kindred to that other adjective born of a proper noun: Orwellian. 1984 has come and gone, but The Trial is still in session.” The aforementioned anthology, Tales of the German Imagination, contained my translation of “In the Penal Colony,” one of his most chilling and prescient tales, and might well have been sub-titled Kafka’s Precursors and Progeny. In hindsight, it is not so much that my translation of fairy tales and other tales of the German fantastic informed my take on Kafka, but rather the other way around, that a consciousness of Kafka retroactively prescribed my appreciation of a tradition that culminated in Kafka.

AF: Konundrum is a collection of Kafka’s longer stories, aphorisms, and excerpts from his journals. You made the selection, so this is your personal vision of the writer. (You have re-titled the story that is commonly known as “The Metamorphosis” in English as “Transformed.”) What portrait of Kafka were you trying to create? In what ways does it differ from the standard view?

Wortsman: I was not trying to create any particular portrait of Kafka, other than that of an author of great sincerity, wit, and prescient vision. Jill Schoolman, the founder and guiding light of Archipelago Books, allowed me the editorial license to proceed without a road map through the author’s opus of published and posthumously discovered works. Limiting myself to his shorter texts, which I think are superior to his novels, I picked only those that spoke to me, from his first preserved jotting, the dedication to a book he gave a friend, to the last scribbled wishes of the dying Dichter, whose tuberculosis of the larynx made speech too painful, left on scraps of paper preserved by his friend and doctor Robert Klopstock. The standard view of Kafka reduces him to the patron saint of neurotics. I hope, at least, that my selection highlights his considerable strength in enduring imagined torments that prefigured actual calamities to come.

As to my new rendering of “Die Vewandlung,” heretofore commonly translated into English as “The Metamorphosis,” I sought, in the spirit of the author, to deflate the highfalutin, Greek-rooted English title, too precious, it seemed to me, for the crass reality of a traveling salesman reduced to a monstrous bug. Like the R&B master James Brown, Kafka starts right off on the one beat, stating the situation: “Waking one morning from restless dreams, Gregor Samsa found himself transformed in his bed into a monstrous bug.” The predicate verb “verwandelt” (transformed) crops up repeatedly throughout the text, best bespeaking its essence, and so best suitable as a title.

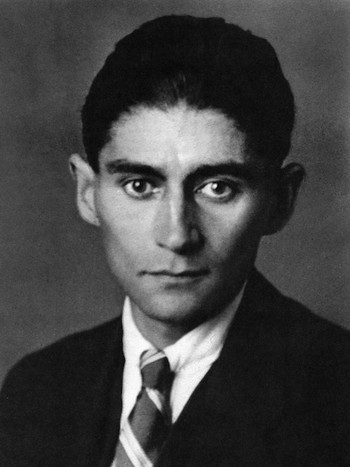

Franz Kafka. Photo: Wiki Commons

AF: The publisher claims that this volume “refreshes the writer’s mythic storytelling powers for a new generation of readers.” Kafka had much to say to the 20th century – what does he have to say to the 21th century?

Wortsman: Since we have only very recently forded the hurdle of the latest fin-de-siècle, it is difficult to characterize the present time and its imperatives. Kafka perceived a creeping terror in the first decades of the 20th century, a terror that ultimately culminated in the gas warfare of World War I, the institutionalized torments of the Holocaust and the cataclysm of the A-Bomb, as well as subsequent horrific genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, and Syria. If anything, the terror has become more generalized in the 21st century. Terrorism has crystallized into a factor in our lives almost as constant as the weather report. We are all bugging out. It sometimes seems as if the psychic microbe underlying Kafka’s narrative constructs seeped out and infected reality. His texts remain one of the best guides and road maps we have to interpret the situation.

AF:Among the pieces in Konundrum, which gave you the most trouble to translate? And which is your favorite?

Wortsman: Two texts, “Investigations of a Dog” and “The Burrow” gave me the most trouble and the greatest grief to translate, though I deemed them essential to my selection. I believe that had Kafka lived, he would have whipped them into a tighter telling. German sentences are by their very nature long and convoluted, but some of the seemingly endless sentences in “Investigations of a Dog” proved so daunting as to make me want to tear my hair out in my attempt to come up with a faithful English rendering. “The Burrow” describes a creature’s entrapment in an underground stronghold of its own devising. I heard of an eccentric wealthy couple so concerned about the security of their palatial dwelling that they fired the watchman and moved into his cottage to keep watch. Kafka was clearly onto something, but I believe that he got tangled in the telling. Consequently in this one instance I took the liberty of translating a representative excerpt.

My unquestionable favorite is his topsy-turvy fable, “Report to an Academy,” an ape’s account of his decision to seek release from bondage by aping humanity. True to German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel’s brilliant bon mot: “Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny,” i.e. the notion that the development of an individual organism incorporates all the intermediate evolutionary stages of its species, interwoven in Kafka’s narrative fabric are the evolution of mankind, the child’s coming to consciousness, and the preposterous and futile efforts of Middle European Jews to assimilate in a hostile society—all able to simultaneously weep and laugh at themselves in the process. A half-painful, half-pleasurable laughter carried me along in the translation from line to line, from the ape’s first encounter with alcohol to his sad and seedy account of sex: “When I get home from banquets, scientific assemblies, and congenial soirées, a little half-tame chimpanzee awaits my pleasure, which I take with her in an apish way. I have no desire to see her in broad daylight; her face has the mad expression of the bewildered half-tamed animal; I alone can see it, and it positively repels me.” Like Mick Jagger, Kafka’s apish alter ego can’t get no satisfaction, but I hope that my translation may afford the reader a modicum of pleasure and insight.

Peter Wortsman’s recent and forthcoming publications include a travel memoir, Ghost Dance in Berlin, a Rhapsody in Gray (Travelers’ Tales, 2013)—for which he won a 2014 Independent Publishers Book Award (IPPY); a novel, Cold Earth Wanderers (Pelekinesis, 2014)—a finalist for Forward Reviews’ INDIEFAB Science Fiction Book of the Year; a collection of short fiction, Footprints in Wet Cement (Pelekinesis, forthcoming 2017); and a translation of The Creator, by Mynona, aka Salomo Friedlaender (Wakefield Press, 2014). Wortsman was a Holtzbrinck Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin in 2010 and a Fellow of the Österreichische Gesellschaft für Literatur in Vienna in 2016.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Archipelago-Books, fiction-in-translation, Franz Kafka, german, Konundrum, Peter Wortsman

Thanks for this, very glad to know there’s a new edition of Kafka, especially a curated one with fresh translations and excerpts from the whole range of his prose. I know a few dedicated readers who don’t respond to the fiction as much as to his notebook thoughts, philosophical observations, etc. I wonder if the translator included one of my favorite episodes: the scene from The Castle with Amelia, the country girl summoned to be the mistress of Barnbas, one of The Castle’s bureaucrats.