Theater Review: Body Awareness — A Lesson in Human Awareness

This is a play where characters don’t remove their clothes but the walls they’ve built to protect their inner selves.

Body Awareness by Annie Baker. Directed by Paul Daigneault. Presented by SpeakEasy Stage Company at the Boston Center for the Arts, through November 20.

Adrianne Krstansky (left) is upset to learn that her partner (Paula Plum, right) is going to pose nude for a controversial photographer in a scene from SpeakEasy Stage’s production of Body Awareness. Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective Photo.

By Chantal Mendes

Despite the vaguely suggestive playbills for this production, there is no actual nudity in Body Awareness. At least, there’s no physical nakedness. Instead, Annie Baker’s characters strip themselves down to their raw emotions: this is a play where characters don’t remove their clothes but the walls they’ve built to protect their inner selves.

Essentially, the body awareness the script explores is not a matter of a healthy self image but a more nurturing awareness of the bodies and souls around us.

At the beginning we are introduced to three characters that make due with an emotionally disconnected space. Phyllis is a professor at the local college in Shirley, VT, the home turf of two other Baker plays currently being staged at the Boston Center for the Arts, the Huntington Theatre Company’s Circle Mirror Transformation and Company One’s The Aliens. She is in charge of “Body Awareness Week”; her partner Joyce is a teacher at the high school and Joyce’s son Jared is a 21-year-old self-declared “autodidact” who may or may not have Asperger syndrome.

From the start we see Phyllis and Joyce quietly at odds with each other, a tension illustrated poignantly by the excellent Plum. She plays the quiet, somewhat sensitive Joyce in a way that highlights the figure’s inner strength but also her deep insecurities.

Adrianne Krstansky, on the other hand, handles Phyllis with less finesse, portraying her character with a little too much bluster at times for her to be convincing. What’s confusing about Krstansky’s performance is that she can’t pull off taking Phyllis from patronizing to complacent in less than five minutes of stage time. First she’s scoffing at Joyce’s claim that being a high school teacher qualifies her as an academic, then she’s cuddling her wounded partner. It’s a bit of a roller coaster, but perhaps that’s what is needed to bring Phyllis to ornery life—Joyce has her hands full trying to smooth over her partner’s contradictions.

Frank, a visiting artist who takes photographs of nude women, supplies the drama’s tipping point, turning Phyllis’s little family topsy-turvy. Richard Snee is surprisingly funny as the older, semi-Buddhist photographer whom Joyce likes and Phyllis finds repulsive. We don’t really find much out about Frank, but that is not important. He is the catalyst that kicks off change, and Snee is the perfect personable actor for the job. He infuses his performance with concrete details but also supplies enough mystery to leave you wondering about his agenda. You can’t figure him out, but you like him nonetheless.

Jared is much less likable at first as the youngest member of the fragile family. Gregory Pember is almost too good at playing a young man struggling with symptoms of Asperger’s, unable to handle his own wild moods and difficulties with social interactions. Initially, Jared’s just plain annoying, but slowly Pember reveals the sensitive side of the bedeviled character. Instead of highlighting his frustration with his shortcomings, the script shows us Jared’s fear of being labeled a “retard.”

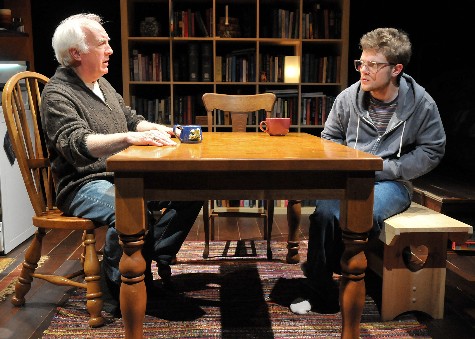

Frank (Richard Snee, left) coaches a young man (Gregory Pember, right) on how to meet women in a scene from SpeakEasy Stage’s production of Body Awareness. Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective Photo.

Frank and Jared establish a rapport that is intensely amusing as well as touching. Jared clearly struggles with coming to terms with his handicap, but finds in Frank not only an outsider’s blunt opinion but also a friend who confidently tells him, “I don’t think you’re retarded.” It is this act of empathy that triggers the play’s central conflict: there would be no reason for the two women, or Jared, to examine themselves and their suppressed desires or fears.

Ultimately the three characters pivot around Frank, spinning in their own little orbits of confusion until they’re out of control and need to band together for stability. Early in the play, Phyllis is fairly sure of herself as she stands in front of the assembly at school announcing she is in control of events. Later on she has become a weeping mess, her emotions flooding to the surface. Krstansky shines in these moments. Her nervousness during the scenes when she speaks in front of the school assembly is painful to watch, but only because she makes it so easy for the audience to put themselves in her anxiety-ridden shoes. Joyce reaches her breaking point after she decides to pose nude while Jared’s attempt to seek out a sexual partner takes him to his emotional limit. The final scene suggests how far the members of the small, somewhat dysfunctional family have gone forward by learning to see things from another person’s perspective.

Body Awareness is the perfect title for this affecting play because Baker’s characters have become more aware and in tune to the wants, needs, and deep desires of others. At the end, Frank serves as an observer (a stand-in for dramatist Baker?), holding his lens up to preserve moments of precious (and rare) human understanding.

Tagged: Annie Baker, Body Awareness, Chantal Mendes, Paula Plum, Shirley, SpeakEasy Stage Company, Theater

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Bill Marx and theartsfuse, theartsfuse. theartsfuse said: A review of one of the trio of plays by Annie Baker now at the Boston Center for the Arts … "Body Awareness" http://fb.me/KXis10QN […]