Book Review: A. B. Yehoshua’s “The Extra” — A Genius for Dissecting Family Matters

This canny writer is concerned with the kind of complicated family relationships that engaged his Jewish literary forebears — Sholem Aleichem, I.M. Peretz, S.Y. Agnon, and even his great peer, the poet Yehuda Amichai.

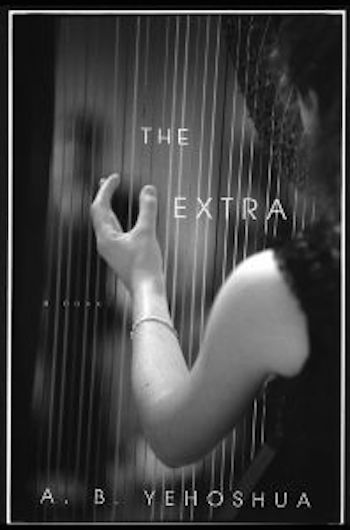

The Extra by A.B. Yehoshua. Translated from the Hebrew by Stuart Schoffman. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 240 pages, $24.

By Roberta Silman

A.B. Yehoshua is not only a great Hebrew writer, but a great writer, period. His Mr. Mani is often cited as his masterpiece, and it is a marvelous book that requires as much attention from the reader as any contemporary book I know. However, his other books are sometimes not taken as seriously as they should be because they are often about domestic arrangements (earmarked as “women’s subjects”) and also because they are sly and humorous and accessible, even in translation. But don’t be fooled by this canny writer whose concerns are the complicated family relationships that engaged his Jewish literary forebears — Sholem Aleichem, I.M. Peretz, S.Y. Agnon, and even his great peer, the poet Yehuda Amichai.

His newest novel, The Extra, seems fairly straightforward when you start to describe it, but it is actually filled with layers and a wonderful example of what an older writer (he is eighty) can do when he is absolutely at the top of his game. His latest creation is Noga (Hebrew for Venus), a divorced, very independent forty-two year old who refused to have a child, fled Israel to pursue her career as a harpist in Holland, and is now back in Jerusalem because her younger brother Honi needs her for an experiment regarding their newly widowed mother.

Since Honi is the caretaker child, he wants their mother Ima to come live in an assisted-living facility in Tel Aviv near him and his wife and two children. He has even cut an amazing deal with the facility to give Ima a three-month trial, to which she has, also amazingly, agreed. The sticker is that her rent controlled apartment in Jerusalem cannot stay empty because the lawyer for the landlord will seize upon that to terminate the outdated but very desirable lease, and Ima will no longer have a choice. The solution is for Noga to take a three month leave from her job in Arnhem, Holland, live in the Jerusalem flat and let the experiment proceed.

So Noga comes back to her childhood home, which, she soon discovers is also a haven for the haredi children upstairs whom her mother has befriended and who adore watching Ima’s tv. That’s only the beginning. Because Noga will not take any money from him, Honi also arranges for Noga to be an extra in all sorts of performances being staged around Israel — thus the title — and Noga discovers a whole new existence in her native country: adventures she never dreamed of having, including a reunion with Uriah, the husband who divorced her because she refused to have a child and who has remarried and has two children but still loves her.

Although there are some hilarious exchanges, many having to do with her work as an extra, Noga’s refusal to have a child hovers like an unsolved mystery over the novel and creeps into every corner of it — when she is working on a set, when she visits her mother in Tel Aviv, even when she learns that by her absence she has lost the opportunity to play her harp solo in Mozart’s Second Piano Concerto, a piece she adores. And when she buys a whip in the Arab market, supposedly to punish the wild haredi children, the plot becomes even more entangled and interesting.

Yehoshua’s ability to weave his story with so many different colored threads is what keeps us turning the pages, but beneath all those twists and turns are the characters in this novel who all, to a person, grow in surprising ways. He does this superbly in short scenes in the present tense that become more compelling as they become crazier, exactly as conversations and exchanges do in family life.

Yet this is a novel with many themes, as well: music, identity, home, and, in a minor way, beds and sleep and by discreet allusion, sex. Here are Noga, Honi, and Ima after her brother and mother have come to the desert to see Noga in an outdoor performance of Carmen and stayed over in close quarters. At breakfast they talk about the past, how their father Abba came to all of his children’s performances and Ima says, with nostalgia for her youth and her young husband,

“But I’m not feeling young only because of you, Noga,” … “It’s Honi too. We haven’t slept in the same room since he was ten, and last night we went out together and even slept in the same bed, so I’m asking myself why you’d want to imprison such a young mother in an old-age home.”

Grimacing, Honi turns to his sister, but she smiles indifferently. He says to her, “Ima is waiting for me to have a heart attack like Abba, to be rid of my nagging.”

“You won’t have a heart attack,” says his sister. “If, as you said, my heart is made of stone, yours is made of rubber.”

“Children, enough,” says the mother. “I apologize.”

Yehoshua also has a remarkable gift for delivering devastating news with a light touch. Here is Noga as she wakes up after playing a disabled patient as an extra in a war movie:

When the first rays of sunshine filter through the giant roof beams, and silence reigns, she can see in the adjacent hospital bed a man lying on his back, his folded arms spread like wings, as if in midthought he was suddenly arrested by sleep. And because she remembers well who slept that way by her side for many years, she throws off the blanket and walks barefoot to the one who has followed her since she arrived here, her former husband, Uriah, who has turned himself into an extra.

Her heart flutters wildly as she watches the man whose hair has grown whiter since he left her. Now he has stolen his way to her in a torn army uniform and a blood-soaked bandage. And with the first glimmer of consciousness, the new extra senses the agitated gaze of his former wife and breaks out in an ingratiating smirk of apology for the terrible power of an ancient love.

What could be a sentimental moment is saved by that “ingratiating smirk” and yet it also opens up possibilities that neither Noga nor the reader suspect.

Blood also plays a part, as in the passage above, and is crucial to the denouement of this novel, which left me in awe of Yehoshua’s deep instincts and knowledge about women’s lives. How we can change and yearn for what we once eschewed while still preserving our dignity.

In a recent interview in the New York Times Book Review, A.B. Yehoshua confessed that instead of reading the contemporary Israeli novels that come with astonishing regularity to his doorstep, he prefers the classics. As I read that, I thought of Akhmatova’s comment about War and Peace being a great family chronicle rather than a profound meditation on war and the world. (Mir can mean “peace” or “the world” in Russian.) I applaud Yehoshua for his literary taste and suspect that his reading strengthens his genius for dissecting family matters, a genius which enriches us all.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: A.B. Yehoshua, Hebrew, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Stuart Schoffman, The Extra