Book Review: “Better Living Through Criticism” — Critical Self-Help

A.O. Scott’s hurrah for criticism is most welcome and should be savored by anyone interested in the connections between the health of the arts and the ways we articulate their value.

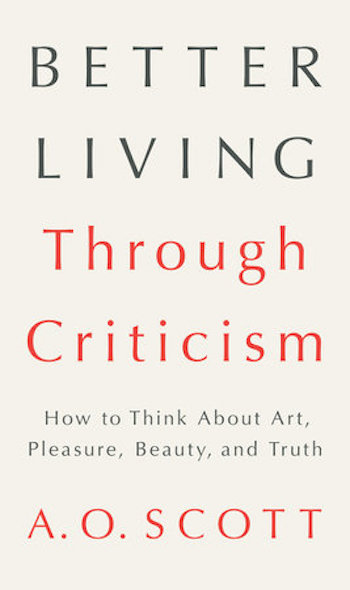

Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think about Art, Pleasure, Beauty, and Truth by A.O.Scott. Penguin Press, 277 pages, $28.

By Bill Marx

I have some qualms about New York Times chief film critic A.O. Scott’s defense of arts criticism in his book Better Living Through Criticism: How to Think About Art, Pleasure, and Truth, so I want to make it clear at the get-go that at a rocky time for criticism he is among the blessed sheep, not one of the the goats.

For one, Scott acknowledges that criticism is rooted in an elemental human appetite: “To judge. That’s the bedrock of criticism. How do we know, or think we know, what’s good or bad, what worth attacking or defending or telling our friends about?” He usefully asserts that arts criticism should serve up “passionate, rational argument about a shared experience.” He understands that the creative act includes a critical component (artists inevitably react to the art of the past or what they see around them), and points out that the need to critique is rooted in “our desire — nearly as strong as the urge toward pleasure itself — to think about, recapture, and communicate our delights, to make them less solitary, less ephemeral.”

Finally, Scott is spot-on when he charges that, in consumption-crazed America, seriously judging artistic value is viewed with deep hostility:

Anti-intellectualism is virtually our civic religion. ‘Critical thinking’ may be a ubiquitous educational slogan – a vaguely defined skill we hope our children pick up on the way to adulthood – but the rewards for not using your intelligence are immediate and abundant.

As consumers of culture, we are lulled into passivity or, at best, prodded toward a state of pseudo-self-awareness, encouraged toward either the defensive group identity of fanhood or a shallow, half-ironic eclecticism. … It is easier to seek out the comforts of groupthink, prejudice, and ignorance. Resisting those temptations requires vigilance, discipline and curiosity.

Bless him for this and his strong belief that criticism isn’t about class-bound elitism, but a healthy exercise of democratic power at the service of building a community through dialogue. Independent and thoughtful discrimination liberates the mind from its petty prejudices: “It’s the job of art to free our minds, and the task of criticism to figure out what to do with that freedom.” I am not convinced that criticism should tell us what to with our liberation (cue corporate-induced delusions of ‘choice’), aside from feeding our hunger for more art and criticism, but — Bravo! May critical stooges of all stripes (on and off the Web), from byte-obsessed editors who reduce arts criticism into a form of cheerleading to reviewers who see what they do as providing a consumer guide. No doubt they will resist Scott’s assertions — especially when they challenge lazy or corrupt editorial practices — but there’s plenty here on the need for judgment to make the open-minded reconsider their descent into publicity mongering.

Where I disagree with Scott — and it is enough of a misstep on his part to undercut his argument — is that, after he does a pretty good job of defining what a critic is supposed to do, he tosses it away. Criticism “is almost impossible to define,” he confesses, a capitulation that leads to a long list of today’s ‘critics,’ which includes academics, bloggers, and contributors to Zagat, Yelp, and Amazon. When he confuses opinion (a statement of preference) with criticism, Scott stumbles into his own trough of anti-intellectualism. Criticism is about backing up its verdicts with reasoned analysis – the all-important why — and that separates arts critics from those who gush yelp, or wag their thumbs. Great critics, such as Samuel Johnson and Edmund Wilson, couldn’t do much in a tweet (argumentative depth depends on a respectable number of words). Anyone can call him or herself an artist or a critic – that doesn’t mean they produce much art or criticism. If the business of criticism is rational argument, as Scott correctly asserts, then the tidal waves of opinion lobbed on the Web are not criticism. Alas, these effusions are being accepted (‘branded’) as criticism, often by publications, editors, and critics who should know better. In truth, there is as much or as little of the real thing around as ever.

Of course, first rate arts criticism is not just substantial evaluation – it is also partakes of what Scott calls the “art of voice,” stylish writing that reflects the personality of the critic. But in a review a writer’s personality is at the service of persuasion. The critic uses all the rhetorical tools at his or her disposal, from scalpel to jackhammer, to convince readers he or she is right (which is not saying that they are). Scott is wise enough to know that real critical authority isn’t anchored in the publication the critic writes for. It is earned by a reviewer’s expertise and intelligence, his quality as a writer, and his passionate exercise of independence. That is an important part of criticism’s elemental democratic power — its proof-is-in-the-pudding virtue. It is a feisty hallmark of the best of the American journalistic critical tradition, from Edgar Allan Poe to now.

To make good on his goal of showing us how criticism can contribute to “better living,” Scott would need to strengthen the distinction between opinion and criticism. In his 1914 review “The Novel Now,” Henry James does just that, arguing that criticism plays a vital part in the education of “our imaginative life.” The aim of criticism “is to make our absorption and our enjoyment of the things that feed the mind as aware of itself as possible, since that awareness quickens the mental demand, which in turn wanders further and further for pasture. This action on the part of the mind practically amounts to a reaching out for the reasons of its interest, as only by its so ascertaining them can the interest grow more various.” Criticism of the arts expands consciousness because it cultivates its powers of judgment; it invites an active, dynamic engagement that does more than make us smarter and more discerning about the culture around us – it also generates curiosity as well as more (and different kinds?) of pleasure. It doesn’t take much to see how this adventure in becoming more discriminating, more adept at articulating why we like what we like, will sharpen our evaluations of politics, people, life, etc, especially when we grapple with other points of view.

“NY Times” chief film critic A.O. Scott. For him, criticism is “a passionate, rational argument about a shared experience.” Photo: Carmen Henning.

Making use of arts criticism as a tool for self-improvement means examining the ways our minds can attain maximum Jamesian expansion. Among the possible approaches: exploring how arts reviewing makes use of “reason” (critical arguments can take wonderfully creative forms), pointing out how tainted editorial practices and ethical shortcuts undermine models for serious evaluation, speculating on how technology helps and hinders arguments about the arts, and looking at the ways popular art tests the traditional limits of criticism (the interactivity of video games, for example). And then there is the trahison des clercs — high profile critics and editors who have argued, from Pauline Kael to BuzzFeed, that criticism isn’t about making arguments, but pushing the hip, the populist, the lowbrow. About a century ago, critic/novelist William Dean Howells complained that the language of advertising was despoiling criticism. Scott has an amusing but pointed section on the overuse of blurb-ready adjectives (he tagged me with “compelling”) — I wish there was more on the decaying language front, given a hundred years of linguistic trashing.

But, instead of talking about how to improve the ways we judge art, Scott elucidates how criticism should be understood as a sophisticated form of art appreciation. The book tends to flit about, less about how we come to conclusions than orating on the ‘big issues.’ The first 100 pages proffers a discussion about taste and the nature of art and, because he argues from the top down rather than the bottom up, the payoff is vague and unsatisfactory. Immanuel Kant and Edmund Burke are brought in rather than the writings of 18th century magazine critics, who were grappling with the same issues in a much less abstract way. Somehow we end up with Scott proclaiming that art’s value has something to do with “pure perception.” That notion may work for visual art, but there isn’t enough here on the different strategies that reviewing books, movies, video games, etc, call for.

When the book focuses more squarely on criticism matters improve, though I wish Scott’s examples were not so potted (the finger is pointed, yet again, at The Quarterly Review and a review that allegedly helped drive John Keats to his death). And I wish there weren’t so many generalizations that don’t hold up: “Criticism has, since roughly the day after the beginning of time, consecrated itself to the veneration and preservation of masterpieces and traditions.” Maybe Kant, Scott, and Giorgio Vasari accept that as their primal directive, but from the day after their birth (in British coffeehouses) arts critics for newspapers and magazines have taken different lines of cultural attack, from shouting that the ’emperor has no clothes” to supporting marginalized art and artists. In the case of H.L. Mencken, the critical imperative is to demolish mildewed mediocrity: “My business, considering the state of society that I find myself, has been principally to clear the ground of mouldering rubbish, to chase away old ghosts, to help set the artist free.” (Note that here criticism is about creating freedom of thought.) At the turn-of-the-century, visual arts critic Henry McBride fought, in his way, for the health of the country’s imaginative life: by convincing frightened, puritanical American readers that Modernism repaid serious attention. Dance critic Edwin Denby saw his goal as educational: he wanted to make his readers better critics.

In the final chapter, Scott arrives at the contemporary plight of critics, demoted to disposable (and increasingly unpaid) content producers. He gets the current situation down cold, from the pernicious impact of technology and Darwinian economics to corporate homogenization. Still, most of his examples barely make it past the 1960s. Could it be that Scott is afraid of kicking up any dust about malfeasance in today’s critical scene? (Ironically, he insists that the best critics eschew moderation.) One of his few recent examples — brought in to rebut claims negative reviews are fading away — is William Giraldi’s 2012 New York Times Sunday Book Review pan of two volumes of fiction by Alix Ohlin. Scott doesn’t mention that Giraldi is primarily a novelist, not a critic. In his 1928 essay “The Critic Who Does Not Exist,” Edmund Wilson savages the journalistic practice (a staple of The New York Times Sunday Book Review) of having novelists review novelists, poets review poets, etc. Wilson points out that a death cage match among competitors and buddies predictably nurtures log-rolling and conflict of interest. Why not give much needed work to professional, independent critics? (I have written from time to time on how the editors at the New York Times don’t seem to know what arts criticism is supposed to be.)

Critic Edmund Wilson — he looked in vain for the “Critic Who Does Not Exist.” Photo: Wiki Commons.

In general, Scott portrays critics as heroic loners (martyrdom is the spiritual reward for their unyielding persnicketiness). There is little here about how professional critics are (or at least were) part of an editorial structure. Reviewers are chosen by editors, and if the latter don’t have their critics’ backs (and firmly impose ethical restrictions) reviewers inevitably default to making easier and safer judgments. The goal is to rock no boats, to ignore the flocks of naked-as-a-jaybird emperors cruising into view. Positive reviews sell product and keep everybody happy.

And that is why critics and editors who care about the future of arts criticism must fight for maintaining its definition — one founded on a knowledge of the form’s traditions. What newspapers used to do is being reborn on the Internet, and there are unsettling indications that journalistic standards are morphing (warping?) under the marketing pressures. If the bedrock notion of what is a news story or an editorial is being chipped away, is it any wonder that the more vulnerable craft of arts criticism is being smashed? If the re-branding of criticism as opinion continues, then the form will revert to the role it played in the early part of the 19th century — advertising. Why should we care about the marginalization of criticism on the Internet? “A failure to judge,” wrote poet/critic Howard Nemerov, “as the example of Cordelia seems to show, has the effect of leaving judgment to the mercies of fools and knaves, or stupids and cupids.”

Scott understands the threat, but he takes an ‘it-has-ever-been-so’ attitude to the current meltdown. Yes, there is plenty of historical evidence criticism has been inept and compromised from its inception, that it has always faced extinction for some reason or another. Scott may be right that we are in a time of transition; there are heartening signs that serious arts reviewing will survive, even thrive, on the Internet. The existence of this magazine and others suggest that the banishment of criticism from mainstream arts pages presents an exciting opportunity for quality criticism, not a dead end. But it seems to me that the situation calls for muscular outcry, incisive confrontation rather than cool-as-cucumber passivity. Instead of kicking back at the diminishment of arts criticism with gusto, Scott favors silky argumentative see-sawing. He typically sets out extremes — between order and chaos, the worst of times and the best of times — and warns us not to accept the lazy, middle way out. He then throws up his hands and says it is all of the above. At times, his style, in an effort to be conversational, becomes a bit too breezy and easy.

Scott’s image of the ideal critic is Anton Ego, the tower of evaluative integrity in the 2007 cartoon Ratatouille who knows perfection when he tastes it. He informs the public and artist/chef Remy that culinary perfection has been attained. After hailing cooking genius, Ego is canned from his newspaper. The story is inspiring — though wouldn’t it have been more satisfying if the editors had stood by their talented reviewer? (Without editorial backup, protests from “powerful hostesses, bankers, and corporation attorneys [who] seemed to feel that their names on the board of any enterprise should render it immune to criticism” would have ended the career of music critic Virgil Thomson at the Herald Tribute.) Is there doubt that Ego was replaced by a person of much less demanding taste? A fan letter W.H. Auden sent to critic Cyril Connolly after reading 1938’s Enemies of Promise suggests the limitations of Scott’s ultimate foodie ideal:

As both [T.S.] Eliot and Edmund Wilson are Americans, I think Enemies of Promise is the best English book of criticism since the war, and more than Wilson or Eliot you really write about writing in the only way that is interesting to anyone except academics, as a real occupation like banking or fucking, with all its attendant boredom, excitement, and terror.

We all have to eat better, but we have to bank and fuck better as well — and there isn’t enough of the “boredom, excitement, and terror” of criticism evoked in these pages. There must be something at stake (observed theater critic Kenneth Tynan) when we make judgments about the arts — these arguments about quality should shake up our lives, hearts, friendships, morals, and perceptions of the world. Scott’s hurrah for criticism is most welcome and should be savored by anyone interested in the connections between the health of the arts and the ways we articulate their value. He makes some indispensable points about a maligned craft. But I wish there was more fire in this sheep’s belly.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: A. O. Scott, arts-criticism, Better Living Through Criticism, criticism, reviewers