Fuse Book Review: “Sweetbitter” — Stale Flavour Du Jour

In no way does Sweetbitter, set in 2006, succeed in doing what you are led to expect of it: to frame the post-9/11 zeitgeist.

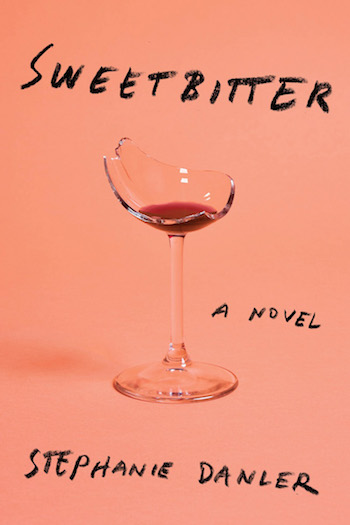

Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler. Knopf, 356 pages, $25.

Author Stephanie Danler — his first novel has been way overhyped. Photo: Twitter.

By Gerald Peary

Elle called Sweetbitter “A book that’ll stay glued to your hands as you race through the pages in one sitting.” Dwight Garner, the New York Times’s hip and urbane book critic, also went wild for this first fiction by Stephanie Danler, 32, based on her years employed at a fashionable New York restaurant, the Union Square Café. More praise for this “exquisite debut novel” comes in ET’s celebrity profile of the blonde, very blue-eyed writer, she photographed at lunch in cutoff shorts. Said ET: when Danler waitressed at Buvette in the West Village, she managed to interest one of her regular clients to read a draft of her autobiographical work, composed while she pursued a New School MFA. He was an at-large editor with Random House credentials; and, with his aid, Sweetbitter landed at Knopf, the most prestigious of publishers. Knopf is said to have offered Danler “a high six-figure, two-book deal…” That’s certainly an awesome Cinderella story, and, in Spring 2016, the media en masse has opted to embrace Stephanie Danler’s fairy-tale talents.

Too bad they are so meager. Too bad, Jay McInerney, Bright Lights, Big City chronicler of the 1980s, is so wrong with his back-of-the-book drum roll claiming that “Stephanie Danler has arrived on the literary scene with a full-fledged, original voice that’s wry, watchful, and wise beyond its years…”

In no way does Sweetbitter, set in 2006, succeed in doing what you are led to expect of it: to frame the post-9/11 zeitgeist, to use the goings-on in a swanky, trendy restaurant as a metaphor for American values in the indulgent, food-nutty society so many of us gleefully inhabit. Sweetbitter hints at all these things, and there’s an occasional sentence which resonates, which gets you to feel what it’s like to be young and trendy and cocky in today’s I-Phone Big Apple. But mostly the storytelling is sketchy and startlingly incoherent, the conversation flow frustratingly hard to follow, and the cast of characters toiling in the food industry almost non-existent as breathing, coherent human beings. And what is mandatory in a restaurant-set book, sensuous descriptions of amazingly prepared food, is also, when tried by Danler, a flat failure. I did not want to rush out and eat fancy after reading this book. Frankly, I struggled hard to even finish Sweetbitter, being so estranged by the prose and the thin narrative.

It quickly bogs down, but Sweetbitter opens promisingly, with our heroine, 22, crossing the George Washington Bridge in her car on a sunny June morning, small-town girl pulled by the magnetic allure of New York. She gets a $700-a-month bedroom in a rental from a friend-of-a-friend in Williamsburg, then subways into Manhattan to the restaurant someone had recommended as the best. It’s the Union Square on East 16th St., no changed name or identity, where the author actually had worked. Pretty girl, our protagonist, and the flirty middle-aged manager quickly agrees to employ her, sort of. Her initiation period means no pay while she learns how the restaurant operates. When she is hired, it’s not for the coveted occupation of being a “server,” the Union Square’s upscale appellate for “waitress.” (A “server” takes orders from “guests,” not customers.) Our heroine is, steps down, a “backwaiter,” folding a thousand napkins, bringing orders and drinks to the tables, but disallowed from conversing with the ”guests.” It’s a humble job, yet those who have it cling to it tenaciously as lifers. Indeed, there is no other life than rigorous restaurant work, or, occasionally, cutting loose after hours for a night of coke lines and/or casual sex.

Our heroine is known as “the New Girl” at the restaurant, and only on page 216 do we learn that her name is Tess. Why not earlier? A writer’s affectation. And why do we know almost nothing about Tess’s past, even though she is the first-person narrator? There are several sentences in all about her parents and the same sparseness of detail concerning college. This makes no sense. Tess has been at university for the four years before this story takes place, and there is NOTHING to carry forth for this 22-year-old? That’s lazy writing by Danler, supplying no backstory. For me, it doesn’t work as an excuse to allege that Tess has no past, that she only becomes a person when she opens her eyes in New York.

As I said at the beginning, Danler is terrible at characterizations. Various servers and backwaiters pass through the book but they are no more than their names. Only two characters have some dimension, one female, one male, and the impressionable Tess gets crushes on both of them. The female is Simone, fortyish and fair. She’s a WASPy beauty exuding breeding and culture who is a long-time manager at the restaurant. Simone has lived in Europe, can wax on about fine wines, and lectures all on the wonders of “terroir.” And then there’s Jake, the beautiful bartender, 30, with ripped jeans and hidden tattoos and a reputation, hard to verify, of having slept with everyone in the place. Has he bedded the older Simone, whom he has known since he was a child on Cape Cod?

Oh, Jake! He’s crude, inexpressive, moody, selfish, sexist, a player of head games, a perhaps one-time PH.D, student who brags that, for two years, he’s stopped reading books and newspapers. Red flag! Red flag! It does make sense that a 22-year-old finding herself would fall for a total dick like Jake. But must she keep obsessing about this faux Brando for more than 300 pages of Sweetbitter? How tedious to keep reading as tormented Tess stays in a sweat for this bad-boy loser. But then Tess is, though as cute as a button, a bit of a loser herself. How can she be really interesting as she is based so nakedly on Danler, the not-very-arresting novelist?

Gerald Peary is a professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.

Refreshingly astringent! Chin-chin, Gerald Peary.