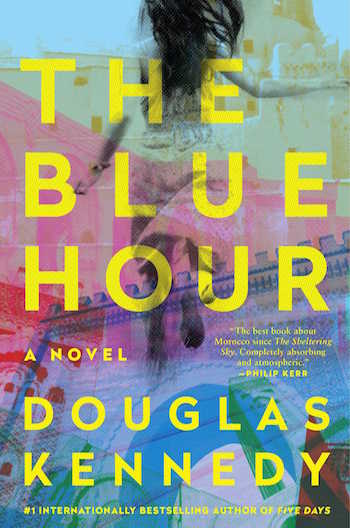

Book Interview: Douglas Kennedy on “The Blue Hour”

“Even in a terrain as epic and mythic and exotic as the Sahara, you cannot run away from the weight of your past.”

Author Douglas Kennedy: an enemy of cliche, especially when it comes to a sense of place. Photo: Christine Ury.

By Bill Marx

What is the “the blue hour”? It is “the hour at daybreak or dusk when nothing is as it seems; when we are caught between the perceived and the imagined.” Best-selling novelist Douglas (Five Days, The Moment, The Pursuit of Happiness) Kennedy is writing about the blues in his latest novel The Blue Hour (Simon and Schuster/Atria Books, 356 pages, 26.99), but this fast-moving psychological mystery yarn, set in Morocco, is not your standard tale of ‘my woman done me wrong’ woe. How could it be, with the Sahara as a backdrop and notions of reality up for grabs?

Yes, a relationship goes off the rails. Robin, an accountant just turned forty, wakes up to find that her older lover has simply vanished. But her pursuit of his whereabouts kicks off a grueling adventure set within an exotic cultural context that presents tests of nerve and endurance as well as exercises in somber revelation. In other words, the book sits firmly in the mode of existential crisis pioneered by Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky. With the added value of Kennedy’s far more equitable eye: his scrutinizing but empathetic sensibility looks at Morocco in the round, with an admirable respect for its nooks and crannies.

Kennedy will be reading from his novel at the Porter Square Books in Cambridge, MA on February 17. I asked him about whether he felt intimidated by Bowles’ classic, his ideas about what it means to write about the ‘exotic’ today, and what he makes of the sharp polarities in contemporary Morocco.

Arts Fuse: Why did you set The Blue Hour in Morocco?

Douglas Kennedy: I am a compulsive traveler – sixty countries visited to-date. And I have spent considerable amount of time in assorted corners of the Arab world (my first book, Beyond the Pyramids – published here by Henry Holt – recounted three months I spent traversing Egypt and all its manifold contradictions). In 2013 alone I was at a book festival in Algiers and Beirut respectively. But of all the countries in the Arab world, Morocco is the one to which I regularly return – an annual visit for over fifteen years (I am a judge for a Francophone book prize in Marrakesh). For me Morocco is completely romanesque: a melange of the modern and the mythic. It is an enormous terrain – almost 1800 miles in length – with Alps-like mountains, visually arresting cities, a massive Atlantic coastline, and – of course – the Sahara. I had been thinking for many years about writing a very modern adventure story, about an American woman thrown into vertiginous circumstances, and slowly becoming unhinged in the search for her wayward missing husband. Morocco – with its mixture of the comprehensible and the unknown, the humane and the sinister, its labrythinian cities and the absolute arid tabula raza that is the Sahara – sruck me as a perfect narrative landscape for my nightmare story.

AF: What were the challenges in writing about this part of the world? The rewards?

Kennedy: I am an enemy of cliche – especially when it comes to a sense of place. When I was writing The Woman in the Fifth [later filmed with Ethan Hawke and Kristen Scott Thomas] I was very conscious of writing about a Paris devoid of its picture postcard veneer. With The Blue Hour I wanted to capture the exotica of Morocco without over-egging the imagery. I also wanted to sidestep obvious statements about the Arab world today, especially at a time of extremism. I hope that what you glean from the novel is the complexity and density of contemporary life in this corner of the Meghreb (as the Francophone countries of North Africa are called); the melange of the exotic and the wholly contemporary. I have many Moroccan writer friends (thanks to my years of book judging in Marrakesh), and they all told me that they thought the novel captured a true sense of the country today – without making prosaic points about its storybook side.

AF: Were you intimidated by Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky? It is also about a troubled relationship, psychological vulnerability, and the hazards of geography.

Kennedy: Of course Bowles’s postwar masterpiece was foremost in my mind when I was writing the novel – and you can read The Bliue Hour, in part, as an homage to his great, unsettling novel. But I was also thinking very much about Patricia Highsmith – another great mid-century American master – and her tales of American couples in vertiginous situations in oppressive foreign climes. Highsmith was also brilliant at the strange byways of guilt and paranoia – and how it can lead you into some very dark places.

AF: In an age of CSI and techno-thrillers, there is something distinctly old-fashioned in the female protagonist’s quest. Was that intentional? How do you feel about the evolution of the thriller?

Kennedy: Indeed I set out to write a good old fashioned adventure story with a modern psychological edge. I am not a Luddite, but when I do write a thriller-esque novel (The Big Picture, The Woman in the Fifth) I am more interested in the way we don’t listen to instinct and allow our multifarious pathologies to dictate a frequently disastrous trajectory. At heart, The Blue Hour is about an increasingly unhinged quest to rescue the unstable husband who has so betrayed her. She puts herself into an ever-accelerating vortex because he is a mirror image of her wayward father: a man whom she could never save from himself. I agree with Freud: all the dilemma of our adult lives have their antecedents in childhood damage, And I use pathology frequently as rhe motivational undercurrent for a thriller.

AF: How has the idea of the “foreign” and “exotic” changed in Western fiction over the past decades? I know you are a fan of Graham Greene. Does his noir vision still hold true?

Kennedy: When Greene was traveling in Mexico (The Lawless Roads) or West Africa (The Heart of the Matter) or Indochina (The Quiet American), to be abroad was to truly be out of touch with the homefront. I remember my travels in Egypt in 1985 – and writing aerogrammes back to by then-wife, booking a trunk call at a major post office, and picking up mail at an American Express or Thomas Cook office. Now in our digitalized age – where even Berbers in the Sahara have cellphones – a novelist has to rethink foreigness. The trick, I think, is to find the unsettling, the disconnected, lurking behind things foreign – and to keep in mind that, even in a terrain as epic and mythic and exotic as the Sahara, you cannot run away from the weight of your past. Maybe that’s the key here – the foreignness of the self as mirrored in the foreignness of the landscape your protagonist is traversing.

AF: At one point, a character quotes Montaigne — “the unknowingness of life is something that we must all embrace.” That idea seems to me to be at the heart of this novel. True?

Kennedy: I just began to touch on this point a moment ago! When creating a character I always begin with the thought: the biggest dilemma we face in life in ourselves. We can never truly know ourselves, anymore than we can find answers for life’s immense mysteries. In the US we are very solution-orientated, and want to believe there is a rational explanation for so much underpinning the human condition. Maybe my three decades in Europe corrupted me – but I embrace the notion that life is messy and largely unsolvable… which is a central reason why it remains so compelling.

AF: Talk about your impressions of Morocco. On the one hand, construction has begun on what will eventually become the world’s largest concentrated solar plant. Yet the trial of Ali Anouzla, editor-in-chief of the Arabic news site Lakome2.com, has just begun. The charges are based on an interview in the German daily Bild, which quoted the journalist as calling the Western Sahara “occupied.” Anouzla risks up to five years in prison and a fine under Article 41 of the current Press Code, which makes it a crime to publish anything that “harms the Islamic religion, the monarchic regime, or territorial integrity.

Kennedy: There are many Moroccos – and, without question, there are many questions about human rights and freedom of expression that could be raised about the country today, Yet it also is an Arab country where you see policewomen, where businesswomen frequently wear Chanel, where there is a degree of social progressivism, and a certain internal stability. But yes there are things that make one uneasy in the body politic as well. My novel concerns an American woman dropped into an escalating nightmare – and one in which she encounters the good, the bad and the ugly within Morocco’s frontiers. As such I steered away from commentary on the internal state of Morocco – because it’s not my country, not my argument. But the novel does provide, I hope, a certain reflection on Morocco’s immense strengths and contradictions – and the fact that to travel there is to truly engage in the idea of adventure.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Douglas Kennedy, fiction, Morocco, mystery, The Blue Hour