Fuse Book Review: The Decision Not to Have Kids — Examined and Defended

This anthology is thought-provoking and often moving; a spearhead into a relatively undiscussed new demographic, revealing a uniquely modern set of choices, and new states of consciousness.

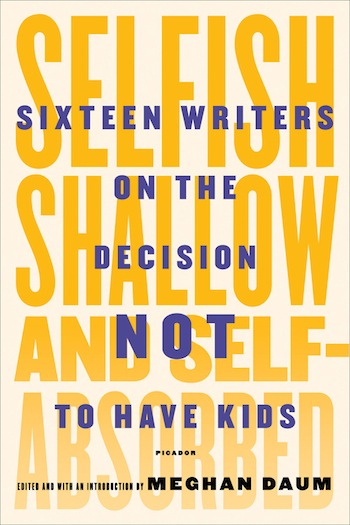

Selfish, Shallow and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers On The Decision NOT To Have Kids , Edited by Meghan Daum. Picador, 288 pages, $26.

by Susan de Sola Rodstein

This is a timely anthology. As several of the contributors point out, despite the increase in (elective) childlessness in the West, our society seems to have become more, not less, “child-centric.” Perhaps when the wish for children was taken as a norm, rather than a choice, there was less of a focus on child-raising as an art than there is today. The bar has been raised high, and in certain socio-economic sectors, according to several of the contributors here, child-rearing seems nearly a “competitive sport”; a search for purity and excellence, starting with organic baby foods and nursery school pre-enrollments, culminating in the stressful marketing of yet unformed teenagers as perfect college applicants.

At the same time, although record numbers of children (and mothers) are living in poverty, we seem to lack serious public discourse, let alone policy, that would address parenthood and working mothers in compassionate, socially conscientious terms. It is one of the positive ironies of this collection that the discussion of elective childlessness leads, inevitably, to talk about children and their welfare, with a passion and incisiveness sometimes absent in the discourse of mothers caught up in the personal demands of modern mothering.

Although the anthology is about non-parenting, only 3 of the 16 contributors are men. Many of my remarks here will be about women and motherhood, not only because they dominate the contributions, but because women still bear the heavier share of childbearing, in physical, psychological, and economic terms; and because women are under more societal pressure than men to defend the choice not to have children. 15 of the 16 contributors are American, and most are late boomers, in middle age, so the contents largely address a very specific American demographic, but a singular one in that it is relatively new. As Pam Houston, 53, puts it, “we are living lives our mothers’ generation couldn’t even imagine.” This would have been a different and more varied volume had it included essays by the very old and the very young.

Yet for all of the seeming homogeneity, the pieces here are as individual and memorable as their authors. Most of these writers are novelists (some journalists, editors, and one blogger — no poets), and are accustomed to thinking in terms of narrative. While some of the essays focus on demographic shifts and social issues, all are to some extent personal and confessional.

The anthology is well-served by its thoughtful and eloquent contributors. It is less well-served by its title, which seems to signal a project mired in defensive postures and a hopelessly polarized discourse. These negative adjectives (“selfish, shallow and self-absorbed”) are asserted in order to be discredited, but they still carry the implication that those who do have children should be selfless, deep, and self-abnegating (tellingly, the antonyms do not cohere as well).

The flip side of the “pro-natal” era, whose underlying message occasionally surfaces in some of the essays, seems to be: if you have the hubris to become a parent, you had better do it perfectly. Have the childless so internalized these (impossible) ideals of motherhood that they have retreated from it in fear of not achieving them? Do they look askance at mothers who fall short of these ideals? If childlessness is not “selfish,” is it not a danger to attach to parenthood an equally extreme expectation of selflessness? It is an irony that this book on childlessness is partly underwritten by a pro-natalist, baby-centric discourse; one that remains so pervasive, it requires a fully charged arsenal of rhetoric to fend it off.

This impression is also borne-out in editor Meghan Daum’s Introduction, in which, by way of Tolstoy’s happy families analogy, she first claims the diversity of paths to childlessness. But then she defines her group of authors with a royal “we”: not hedonist, not ascetic, not haters of children, not unduly scarred, not disengaged, not afraid, and above all, not regretful of their “decision.” Her exclusions betray a wish to present her authors in a socially positive light, but her approach is belied by the actual essayists, among whom many admit freely to not liking children, preferring their own pleasures, fearing loss of autonomy and fearing motherhood. There are, hauntingly, tales of internal struggles to come to a decision, in some cases harrowing, with different degrees of remaining sorrow. Some conclude that they did not ever fully “decide,” but that timing, upbringing, relationships, shifting priorities, and other factors (as with most of us) brought them to the place they are now. And although Daum wishes to show that the ways of childlessness are myriad, judgment is never far off: “You can do it lazily and self-servingly or you can do it generously and imaginatively. You can be cool about it or you can be a jerk about it.”

Fortunately, the quality and subtlety of the volume’s writing improves with its individual essays. Interestingly, Daum admits she had trouble finding them. She approached “dozens” of writers, and the 16 essays gathered here are a “gift.” For some, the terrain was too personal, for others it simply was not of interest, and they felt they had nothing to say about it. So, this is a self-selected group that feels it has something to say. And to Daum’s credit, even though some of the essays “enraged” her in places, she included them.

The range is impressive. The opening essay, “Babes in the Woods,” by editor Courtney Hodell, is a hauntingly lyrical memoir, referencing fairy tale, of her close relationship with her “Irish twin” gay brother, and the changes wrought when he, and not she, became a parent. She recalls her mother, “everywhere and nowhere, constant but peripheral, the separate acts of care like salt grains dissolved in water. It was hard to see where the fun was,” and her childish shock when she realized her mother did not “consider us a single being, like a grove of aspens is said to be.” When she bonds with her niece, she admits, “the ruthlessness I feared…turns out not to be the point of the tale. There are times when the parent enjoys being feasted upon.”

In contrast, the very symbolization and “mystification” of motherhood is deconstructed by Laura Kipnis, a social critic. She lays bare the economic underpinnings of the modern valorization of motherhood. Quoting Shulamith Firestone’s image of childbirth — “like shitting a pumpkin” — she analyzes both the “natural” (nature is “brutal, painful and capricious”) and the “maternal instinct” as socially mediated constructs that disguise and perpetuate glaring inequalities. The economic loss of value in having children (which are now a financial liability rather than an asset) in post-agrarian society has led to a compensatory idealization of them, an attachment further encouraged by a reduction in infant mortality. Motherhood itself, however, is not a highly valued activity, despite the “heightened requirements set by today’s former careerists turned full-time Moms.” And while women themselves help to perpetuate the myth of maternal instinct, motherhood hits women harder, both physically and economically. There is not a comparable concern in society for the many children living in poverty, whose mothers have no choice but to go out to work. Not without bracing humor, she calls for the development of social policies to support mothers, and a more inclusive, socially aware idea of parenthood that includes men.

In contrast, Kate Christensen’s essay emphasizes maternal instinct (albeit a transitory one), but makes few claims beyond her own autobiography, which is fraught with episodes of instability and emotional suffering. She describes a phase in her life when she wanted children badly, albeit held back by her partner and by her own ambivalence:

Where are my children? I felt their absence and loss as if they existed somewhere I couldn’t reach…on the other side of a membrane…I felt as if they were real….It seems to me in hindsight, that it was a biological, hormonal impulse, an imperative that arose when the right moment came, and then, unfulfilled, simply went away over time…I didn’t choose not to have kids, it just happened to me…the bad episode was a good-bye to them forever. I let them go back to the void, those unknown people I would have loved with all my heart and soul but will never know. I can’t miss what I’ve never had.

Similarly, Paul Lisicky’s “Child-Who-Never-Was” is imagined in his story of coming of age as a gay man in the era of AIDS, and who is now the “Child-Who-Might-Never-Be.”

Lionel Shriver, one of the best-known writers here, writes the least personal and perhaps the most fearless essay. She comes closest to fulfilling, with dead seriousness, the defiant subtitle of the collection. She defines the “Be Here Now” generation, a phrase derived from the 1960s that has evolved into an “entrenched gestalt,” in which the final frontier is the self. Hers is a society filled with secular gods and individuals who are not hoping to lead “a good life, but the good life; not asking if their lives are righteous, but if they are interesting and fun.”

An American living in Europe, Shriver is closer to the future demographic problems of the West’s population, aging and declining despite the addition of immigrant populations. She discusses racial and ethnic heritage in this context; the perpetuation of lineage and culture among “white, educated elites.” These are provocative subjects, and she asks, if in lieu of a “poisonous right-wing backlash,” we should “at least allow ourselves to talk about it,” including “the right to feel a little sad.” She writes that in our focus on the individual, we take our heritage for granted; the question is not whether to raise another generation, but whether raising kids will make us happy.

One can only wonder at Shriver’s assumption that the transmission of culture comes about through biology and genes rather than milieu and education. She treads on a slippery slope of racial determinism. Is it naïve, a naiveté perhaps only possible in one who has never raised a child, to think that somehow a heritage is magically transmitted in one’s DNA? It is not. Any child will resemble the prevailing culture in which he or she lives, with all of its cultural mixes and changes, far more than the culture of his or her parents. Procreation is not replication, nor is it conservation. Children grow up to hold on only to what they choose, and that will vary with every individual and change with every generation.

Shriver includes herself in the very group she criticizes, but she is also implicitly hard on women in general. She does not address the fact that women bear the personal and economic burdens of parenthood disproportionately. She interviews three childless women friends, one of whom is quite young, and claims that the stigma of childlessness is on the decline. But all of her subjects are highly accomplished and leading privileged lives, in part facilitated by their childless state: “We’re interesting, we’re fun. But writ large, we’re an economic, cultural, and moral disaster.” Shriver also sees contemporary self-absorption as a form of apocalyptic “insidious misanthropy — a lack of faith in the whole human enterprise.“

In its darkest form, the growing cohort of childless couples determined to throw all their money at Being Here Now — to take that step aerobics class, visit Tanzania, put an addition on the house while making no effort to ensure there’s someone around to inherit the place when the party is over — has the quality of the mad, slightly hysterical scenes of gleeful abandon that fiction writers portray when imagining the end of the world…When Islamic fundamentalists accuse the West of being decadent, degenerate, and debauched, you have to wonder if maybe they’ve got a point.

Not for the first time, I found myself imagining how it would be if the authors had read each other’s essays before publication. What Shriver takes seriously, the “Be Here Now” mentality and the extinction of lineage, Geoff Dyer, the only non-American included, runs with to the point of hilarity in “Over and Out.” This was the only essay that made me laugh aloud. Dyer claims to enjoy the pity (which he craves “like other men crave respect and admiration”) he and his wife receive from those who assume they are not childless by choice. He notes, “By a wicked paradox, an absolute lack of interest in children attracts the opprobrium normally reserved for pedophiles.” He attacks the idea that it is “selfish” not to procreate, to “ensure the survival of our endangered species and fill up this vast and underpopulated island of ours.” He is most hostile to the idea that having children gives life meaning; that “life needs a meaning or purpose!…It would be a lot less fun if it did have a purpose – and then we would all be obliged (and foolish not) to pursue that purpose.”

His tone is humorous, but not without wisdom, and his observations seem inarguable. He puts paid, definitively, to the idea that any special degree of “regret” is reserved for the childless:

….while life may not have a purpose, it certainly has consequences, one of which is the accumulation of a vast, coastal shelf of uncut 100-percent-pure regret. And this will happen whether you have no kids, one kid, or a dozen. When it comes to regret, everyone’s a winner!

Dyer also expresses a refreshing wariness about the anthology itself: “if this is a club whose members feel they have had to sacrifice the joys of family life for the higher vocation and fulfilment of writing, then I don’t want to be part of it. Any exultation of the writing life is as abhorrent to me as the exultation of family life. Writing just passes the time and, like any kind of work, brings in money.” He includes an extended citation on parenthood (the “thwarting circumstance”) and creative failure, from his brilliant book, Out of Sheer Rage:

The perfect life, the perfect lie…is one which prevents you from doing that which you would ideally have done…but which, in fact, you have no wish to do. People need to feel that they have been thwarted by circumstances from pursuing the life which, had they led it, they would not have wanted; whereas the life they really want is precisely a compound of all those thwarting circumstances.

In the hierarchy of obligations children impose, these parents/failed artists in fact “scale the summit of their desires.”

Sigrid Nunez’s elegiac “The Most Important Thing” tackles head-on the question of children and the writer’s life — not just the working writer, but a writer who thinks in terms of George Eliot, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf. Her standard for motherhood is also high. Like a number of contributors here, Nunez has been put off maternity in part by a mother whom she experienced as ambivalent or unfulfilled, a perception which led her to setting up a paralyzing choice between an ideal model of selfless motherhood or none at all. In retrospect, she remains uncertain “whether it was a choice I made or one that was made for me.” She is also aware that this expectation of selflessness does not exist for fathers. There are also those, such as Danielle Henderson, Michele Huneven (“I didn’t trust myself not to re-create what I had known”) and Pam Houston, who cite highly dysfunctional or abusive childhoods as playing a role in their decision. Houston concludes that for her the “perfect trifecta of abuse” (alcohol, physical, sexual) is not the whole story: “thirty years of teaching creative writing has proven to me that my childhood story is as common as a two-car garage.”

A writer friend, John Dunn Smith, quipped that he “believes children are the future. Because it would be really weird if they were the past.” But so many negative childhood experiences are evoked in these pages that it raises the question of whether a wholly happy childhood is itself an imagined construct. If so, it has a lot to answer for. Nevertheless, many more people with bad childhoods have children than forego them. Many more writers have children than writers who don’t. In general, many more people have children than don’t, which Daum herself points out in her Introduction is a good thing. So no aspect of any category of person (writer, man, woman, gay, straight, survivor of an unhappy childhood or captive of an idealized childhood) may be mutually exclusive with the wish to have children, or itself is determinative of the desire not to have them. As Tim Kreider points out, for many of us, “our most important decisions in life are all profoundly irrational ones, made subconsciously for reasons we seldom own up to.”

Inevitably, those with children and those without can only consider each other’s states across a divide of unknowability. The childless know what it was to have been a child, but not what it is to have one, and these two states are not equivalent. A number of contributors are convinced that they would never be able to take on the fears and uncertainties of parenthood because they would be too protective; unable to live with any possible margin of error or injury, unable to achieve equilibrium of any kind: “[I would be]so overprotective I would destroy him and myself in the process” writes Rosemary Mahoney in “The Hardest Art.” Tim Kreider writes, “I would love them so painfully it would rip my soul in half, that I would never again have a waking moment free from the terror that something bad might ever happen to them.”

Editor Meghan Daum –she admits she had trouble finding contributors for this collection.

There is a poignancy to these declarations, knowing that their authors never experienced that dimension of parenthood singularly missing from this collection. That is, parenthood, while irrevocable, is not an absolute and fixed state, but like all others, one that unfolds in time. It involves a gradual letting go, a growing acceptance of risk and uncertainty, that starts from the first moments of a baby’s utter dependency to his or her first unaided steps to full maturity. It’s surprising that the idea of raising a child, which is the most fluid and rapidly changing of human experiences; the quantum changes that inhere in the first 21 years of life, should be studded with labels, larded with certainties, and fixed in time as an unchanging state.

Alternatively, those of us who are parents (I have children), will never know the joys, freedoms, depths, and experiences of a childfree state. As Jeanne Safer, a pioneering writer on the subject puts it, “Nonmotherhood is forever.” Kreider, in contrast to Shriver’s giddy, existential band, sees the childless-by-choice as an existential vanguard, engaged in a daily effort at finding meaning in a world that has largely lost faith:

We childless ones are an experiment unprecedented in human history. We are unlikely, for obvious reasons, to take over…individually we are doomed to extinction. Although so is everyone else. But as an option, an idea, who knows? We may thrive and spread…At the risk of sounding grandiose and self-congratulatory again, I’ll venture to suggest that we childless ones, whether through bravery or cowardice, constitute a kind of existential vanguard, forced by our own choices to face the naked question of existence with fewer illusions, or at least fewer consolations, than the rest of humanity, forced to prove to ourselves anew every day that extinction does not negate meaning.

When I told friends I was writing this review, I was warned by many women friends without children not to “explain” the lives of those who do not have them. And one, herself a mother, put it most succinctly, “women should be the first to stop asking, or answering this question.” The emphasis on the privacy of decisions around parenting is essential, especially given that women’s reproductive choices are under constant threat, not to mention the biases that electively childless women endure.

Yet this silence seems to carry in it the seeds of an atomism that diminishes the discourse and practice of motherhood, resulting in the isolation and impoverishment, both actual and intellectual, of mothers — the very isolation and impoverishment from which many of these thoughtful, ambitious writers admittedly fled. Motherhood needs to achieve a fine and sensitive balance between the personal and the civic. This anthology is thought-provoking and often moving; a spearhead into a relatively undiscussed new demographic, revealing a uniquely modern set of choices and new states of consciousness. One looks forward to the day when the stigma is gone, when the essays in this volume may come to seem quaint, even dated, even while they remain illuminating and sometimes heartrending. Yes, we should stop asking the question, but the answers are worthwhile.

Susan de Sola Rodstein holds a Ph.D. in English and American literature from The Johns Hopkins University. As Susan de Sola, her poems have appeared in The Hudson Review, The Hopkins Review, Measure, River Styx, and Ambit, among many other venues. A David Reid Poetry Translation Prize winner, she lives near Amsterdam with her family.

Tagged: elective childlessness, Meghan Daum, Motherhood, non-parenting, Raising Children, Selfish Shallow and Self-Absorbed