Book Interview: Todd Tietchen on Jack Kerouac — Torn Between Routes and Roots.

“The aspiration in presenting these works together is that a more rounded comprehension of Jack Kerouac might finally be realized or acknowledged by both general readers and scholars.”

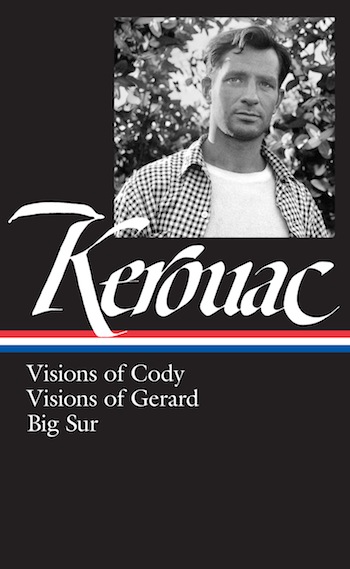

Jack Kerouac: Visions of Cody, Visions of Gerard, Big Sur. Edited by Todd Tietchen. Library of America, 816 pages, $35.

By Bill Marx

In an interview published in his 1976 collection of assorted prose, Picked-Up Pieces, John Updike had some surprisingly good things to say about Jack Kerouac: “He attempted to grab it all; somehow to grab it all. I like him.” When the questioner bridled at the comparison, Updike went to explain that “Kerouac was right in emphasizing a certain flow, a certain ease. Wasn’t he saying, after all, what the surrealists said? That if you do it very fast without thinking, something will get in that wouldn’t ordinarily.” That unfamiliar notion of Kerouac as a surrealist, American style, grabbing at the nooks and crannies of consciousness, a restless experimentalist playing around with form and ideas, is at the forefront of the three works (Visions of Cody, Visions of Gerald, and Big Sur) included in the third volume of the Library of America’s edition of Kerouac writings. Earlier entries in the series were dedicated to his Collected Poetry and Road Novels 1957-1960 (On the Road, The Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, Tristessa, and Lonesome Traveler).

Kerouac is best known for the hallucinogenic comradeship evoked in On the Road, raising the question of what these later works add to our understanding of his literary development and the Beat sensibility. It seems to me that these books — determinedly unruly, overflowing with streams-of-consciousness, lyricism, and self-indulgence — take Updike’s perception to expansive extremes. How much can Kerouac spontaneously grasp and then articulate within the pages of a text? Two of the volumes here were written in the ’50s but were not published until years later (Visions of Cody in 1972, Visions of Gerard in 1963), while 1962’s Big Sur registers Kerouac’s grim, at times almost nihilistic, disappointment at the cultural transformation he had spawned in his ‘Road’ novels. I sent a few questions about what these books tell us about Kerouac and his art to editor Todd Tietchen, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell, and the editor of Jack Kerouac’s The Haunted Life and Other Writings.

Arts Fuse: The books in this volume are not among the more celebrated Kerouac volumes. What do they tell us about the author of On the Road that admirers need to know?

Todd Tietchen: I think it’s important to point out that Kerouac considered Visions of Cody his masterpiece, the superior rendering of Neal Cassady and the events of On the Road. Visions of Gerard, a more focused narrative about Kerouac’s childhood in Lowell, Massachusetts, also remained particularly dear to him.

What this reveals about Kerouac is the extent to which he remained torn for most of his life between the existential allures of movement (a certain vision of personal liberty figured in “the road” and migration) and the need to feel rooted somewhere, to be committed to a place and its life ways. I believe that Kerouac’s most dedicated readers already comprehend this formative tension within his work between routes and roots, and perhaps presenting Cody and Gerard side-by-side shall make this foundational duality more evident to others. Moreover, that dualism expresses itself in a more harrowing way in Big Sur, as its persistence contributes to the mental exhaustion and breakdown at the center of that work. Ultimately, the aspiration in presenting these works together is that a more rounded comprehension of Kerouac might finally be realized or acknowledged by both general readers and scholars.

AF: Do these books deepen our understanding of Kerouac’s Beat sensibility in a surprising way? Does their experimentalism, a sort of free-associational free-for-all, an at times hysterical search for linguistic ecstasy, add a new wrinkle to our understanding of Kerouac the rebel?

Editor Todd Tietchen — Taken together, the trio of works in this volume require that we acknowledge the formal diversity embodied within Kerouac’s writings.

Tietchen: Kerouac had a complicated relationship to “Beat sensibility,” as you’ve called it. “Beatness” really ended up being a double-edged sword for him. While it allowed a way for publishers to brand him during the 1950s, he spent much of his life trying to escape being confined to that image. I think this comes across powerfully in Big Sur, which reads in many ways as an indictment of the Beat ethos and his complicity in it.

More specific to the three works collected in this volume, I think they deepen our understanding of the experimental richness of Kerouac’s oeuvre beyond free-associational prose. Cody obviously takes Kerouac’s interests in spontaneity, or an aesthetics of immediacy, as far as he was capable of taking them. Gerard’s experimentalism might be located in its syncretic blending of Catholic and Buddhist religiosity in a way that remains highly uncommon, along with its attempts at reconstructing the perceptions of a young child immersed in family trauma—the death of the nine year old, Gerard Kerouac. Big Sur’s experimentalism might be located in the fact that it’s an anti-road narrative of sorts, a deconstruction of Kerouac’s earlier artistic ambitions. There’s also the fact that Big Sur is a multiform work, a prose narrative concluded with the ambitious poem, “Sea.” Taken together, then, these works require that we acknowledge the formal diversity embodied within Kerouac’s writings. Again, I think that hasn’t been properly acknowledged, or has been obfuscated at times behind the long shadow of his experiments in spontaneity.

AF: All three of these volumes are highly autobiographical, but Kerouac isn’t interested in conventional narrative. They jump from meticulously delineating interior states of mind to lovingly describing concrete objects. Strong elements of nostalgia are mixed in with numerous intimations of mortality. Would you call Kerouac a writer haunted by death?

Tietchen: That’s a fair assessment. I think that Gerard makes that fairly evident, anchoring Kerouac’s obsessions with mortality in the formative event of his brother’s death at the age of nine. His concerns with mortality become permanently figured within his artistic vision via the Catholic drama of the cross and the Buddhist metaphysics of impermanence, as turns to both at various times in his own life to deal with his intimations or hauntings. They also provide the principle impetus for his art, which becomes a cycle of remembrance or nostalgia offered in response to human impermanence, and extended across a voluminous collection of works that Kerouac dubbed the Duluoz Legend.

AF: Kerouac’s Visions of Gerard offers a gentler vision of Lowell, MA, his birthplace, than in some of his other books. What was his relationship to his birthplace and how was it reflected in his fiction?

Tietchen: Kerouac’s relationship to his birthplace complexly mixes sentimentality with the desire for escape or flight—an experience that I think is common to many. Aside from that, Kerouac’s portrayals of Lowell in Gerard and elsewhere remain of tremendous ethnographic value in that they capture the depths and contours of French-Canadian life in New England, along with providing us with snippets of the working class French spoke in neighborhoods such as Lowell’s Little Canada. Preserving that particular immigrant and American experience in his Lowell writings is actually one of Kerouac’s central accomplishments as a writer (and literary ethnographer).

AF: I am dating myself, but when I was in high school Big Sur was a far more influential book than On the Road — it fit in with the vogue for dropping out — not to explore America, but as part of a quest for higher enlightenment. Yet Kerouac seems to be unhappy with the counter-culture longings he helped to create. At one point he writes that “after all the poor kid actually believes that there is something noble and idealistic and kind about all this beat stuff …” Was he trying to escape his responsibility for inspiring free-spirited youth in this book?

Tietchen: I agree with this assessment and much has been made of it by Kerouac’s many biographers, and more generally by scholars of the Cold War era. Kerouac’s increasingly hostile attitudes toward the emergent counterculture are typically related to the detrimental influences of alcohol abuse, which helped contribute to the conservative crankiness of his 40s. I’d deepen that analysis by pointing out that Kerouac was avowedly anti-political his entire life, having never voted in a single election, and I think he was thus made incredibly uneasy about the politicization of his work by young people in the 1960s. That unease was compounded by the fact—and I think this is also clear in Big Sur—that he didn’t want to be iconized, as being transformed into an icon is inherently reductive. His concern, to extend this a bit further, is that the breadth of his work as an American artist would be obscured behind iconography. Again, I think that’s why these publishing efforts by Library of America are particularly weighty, as they ask us to deal with a more robust rendering of Kerouac and his lifework.

Jack Kerouac — his portrayals of Lowell, MA in “Gerard” and elsewhere remain of tremendous ethnographic value.

AF: At one point in Big Sur Kerouac refers to the “ups and downs and juggling of women… and the secret underground truth of mad desire hiding under fenders under buried junkyards throughout the world …” Kerouac is fascinated by sexual power — why are women such shadowy presences in these works, certainly when compared to the male characters?

Tietchen: Several years back, Louis Menand likened the Beat writers to the Rat Pack, as both remain highly celebrated “boys clubs” of the postwar era. That being said, the “shadowy presence” of women in Kerouac is problematic, for he was in fact surrounded by an impressive cast of female artists, writers and intellectuals for much of his life. Yet Kerouac seems more interested and attuned to male relationships and I think that this in part traceable to generational insecurities. Kerouac lost a great number of male friends in the Second World War and this no doubt contributed to his idealization of male friendship or male bonding. Where this becomes particularly interesting for me is that Kerouac’s focus on men works to destabilize Cold War masculinity even as it seems to celebrate it. Cody and Gerard are books that valorize male muses in effusive prose, a quality out of step with the tight-lipped John Wayne masculinity of the postwar period. In this sense, Kerouac is more aligned with the openly emotive method acting of James Dean that he is with the Rat Pack, and seems to be registering a shifting in American masculinity while nevertheless sentimentalizing manliness. The issue of masculinity in Kerouac requires a great degree of nuance as he’s largely a figure on the cusp, and I believe there remains a deal more to be said on this topic.

AF: Do you have a favorite passage in any of the works in this volume? Why do you find it so significant?

Tietchen: I think there’s something of great value in each of these books. I appreciate the experiments with tape recording at the center of Cody, for Kerouac anticipates Warhol filmic aesthetic of the commonplace or the inane (as in Empire) and suggests that newly available recording technologies might help realize such an artistic vision. I think that the scene in Gerard when Emil must explain to his children why they live in a world “where the cat must eat the mouse” ranks among some of Kerouac’s best writing, as does the poem, “Sea,” at the conclusion of Big Sur.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Big Sur, Jack Kerouac, Library-of-America, Todd Tietchen, Visions of Cody