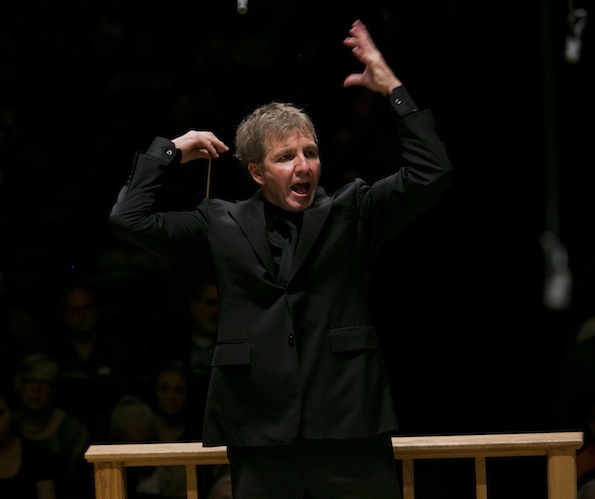

Classical Concert Review: Thierry Fischer Conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra

As they often do in repertoire that doesn’t turn up too frequently, the orchestra responded to the music with heightened sensitivity and attention to detail.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The output of few symphonic composers has been as unjustly neglected as Carl Nielsen’s. A contemporary of Sibelius, Nielsen wrote six symphonies between 1892 and 1925. It wasn’t until the 1960s that, due in large part to Leonard Bernstein’s persuasive advocacy, it seemed the Nielsen blight was about to be lifted. That wasn’t quite the case. Over the last fifty years, Nielsen’s popularity has ebbed and flowed, but he remains largely in the programming cold.

How fortunate, then, when his music does turn up in concert, as it did this weekend in the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s (BSO) fourth subscription series of the season. Thierry Fischer, a Nielsen specialist, was on hand to superintend a program that closed with the composer’s Symphony no. 4 (“The Inextinguishable”).

This weekend’s concerts and next’s were originally slated to be led by Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos. Frühbeck’s death this summer opened the way for Fischer to make his BSO debut, but, more remarkably, both programs (the main piece next week will be the German Requiem) allow the BSO to pay tribute to one of their favorite and, in recent years, most important guest conductors in especially appropriate fashion. There was more than a sense, in Saturday’s invigorating account of “The Inextinguishable,” of the orchestra honoring Frühbeck own inimitable memory with playing of great responsiveness, nuance, and drama. One imagines the old maestro would have been more than pleased.

As a symphony, the Nielsen Fourth has its distinctive features. Its four movements proceed without pause. The orchestral textures are often highly contrapuntal. Nielsen’s orchestration is very organic: austere and direct, but a bit more colorful than Sibelius’s. And it’s heavy on drama, especially – but not only – in the finale, with its famously dueling timpanists.

On Saturday, that finale was nothing short of a thrill ride, with Timothy Genis and Daniel Bauch manically pummeling away. So, too, was the opening movement, its angular opening theme played with slashing intensity and its enigmatic development given an eerily precise rhythmic profile. The beautiful second movement intermezzo was etched with a different type of precision, genial and warmly tonal, while the slow movement, with its searching main theme, powerfully brought the Symphony’s musical drama to a head.

It was a reading that made you wish that the BSO played more of this stuff. As they often do in repertoire that doesn’t turn up too frequently, the orchestra responded to the music with heightened sensitivity and attention to detail. I’ve heard performances with a bit more sweep – Bernstein’s old recording and Alan Gilbert’s new one come to mind – but Fischer’s burned satisfyingly hot.

Brahms’s First Piano Concerto is, in contrast to anything by Nielsen, no stranger to Symphony Hall. The Viennese pianist Rudolf Buchbinder was this weekend’s soloist.

Buchbinder isn’t the type of pianist to blow you away with his technique. His performance here drew you, instead, with the depth of its inward focus. He managed to get a wealth of color out of his instrument: there were moments in the unaccompanied sections of the first and second movements where I could have sworn I heard orchestral sonorities rising from the keyboard.

And the best moments of Buchbinder’s performance came in the introspective sections of those movements, especially in his time-stopping account of the second. The latter was a beautiful essay: poetry in notes. Some passages in the finale were a bit muddled, but, by that time, Buchbinder’s reading had taken on such a strongly musical and energized cast that small textural lapses became trifling details.

For his part, Fischer strongly emphasized the rhythmic character of Brahms’s writing and also drew a wide palate of tonal shadings from Brahms’s sturdy, if never terribly brilliant, orchestration. His was a solid, lyrical reading that flowed naturally and brought just enough touches to the fore – low strings emphasizing the piano’s left-hand attacks; winds dovetailing seamlessly with the solo piano; the serious jauntiness of the finale – to make it an especially pleasing one. Hell, even the canonic writing in the first movement development didn’t sound like an obligatory counterpoint exercise. When that happens in Brahms, you know things are clicking.

These concerts mark an auspicious debut for the BSO’s newest guest conductor. I look forward to his return, hopefully before too long. With him, then, I trust he’ll bring some more Carl Nielsen. Heaven knows, his is music more than worth hearing.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Boston Symphony Orchestra, Rudolf Buchbinder