Theater Interview: Beau Jest Turns 30 — Davis Robinson on Moving into “Apt. 4D”

We do it for the joy and communitas of making theater together much as we do for responding to the world around us through art.

By Bill Marx

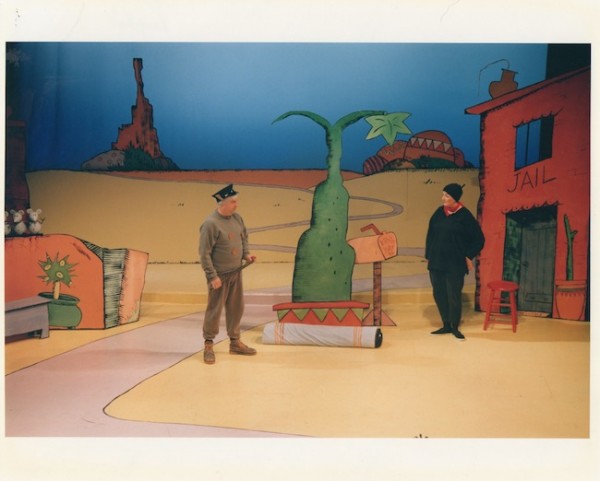

After 30 years, Beau Jest Moving Theatre is still in motion, which is quite a feat given that most small to medium stage companies fall into the category of the quick and the dead. I have seen all of the company’s productions during its three decades, and can testify that a key to its survival has been artistic director Davis Robinson’s belief that physical movement on stage (at the service of either comedy or pathos) should be shaped by intelligence and imagination rather than catering to the audience’s Pavlovian responses. (Call his approach Jest du Soleil.) With its productions of original material and challenging adaptions, ranging from Motion Sickness and Samurai 7.0 to Krazy Kat and Tennessee Williams, Beau Jest has consistently provided smart, funny, and unpredictable experiences, producing memorable work with a strong conceptual (satiric and/or abstract) edge, using the minimal to accomplish the maximal. When it comes to fantasy, they are the real thing.

This time around Beau Jest is taking a cue from the movies — film noir to be exact. Apt. 4D (June 12 through 21 at the Charlestown Working Theater, Charlestown, MA) deals with the isolated tenants of a mysterious building — the ordinary begins to morph into the threatening, dream breaks into mundane reality. I e-mailed Robinson some questions about the show, how it fits into the development of the company, and what feels like for Beau Jest to turn 30. Does this mean we can never trust the troupe again?

Arts Fuse: What was the impulse behind creating Apt. 4D? What are you responding to in the culture?

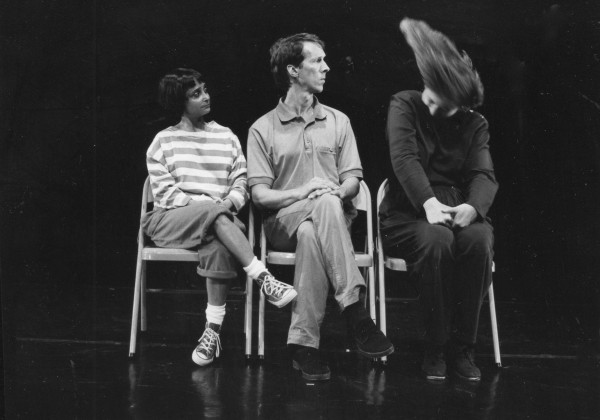

Davis Robinson — For him, “Apt. 4D” is “a delight to perform in; it is a great personal challenge to be able to make every moment count and play as intended.”

Davis Robinson: We wanted to create a comic mystery with lots of movement and detailed observations of human behavior. We started by looking at contemporary obsessions with social media and how we present ourselves, but physically that wasn’t very inspiring. Lots of staring at iphones and talking to computers. Then I remembered a building that has always intrigued me: The Brattle Arms, over by A.R.T.. We have similar buildings in Portland — The Longellow Arms, The Roosevelt—pre-war apartment buildings evocative of Hitchcock’s Rear Window. There is an air of mystery and romance about those buildings, and an existential sense of sadness, a clichéd feeling that people have been there since the 1950’s living lives of quiet desperation. That’s what led us to the notion of everyday people just trying to get through the day, which is a robust setting for the quotidian physical comedy Beau Jest is known for — bits of silent play in the hallways, courtyard, and laundry room in a building full of neighbors who don’t really know each other.

To stir things up, we added a film noir angle. Midwinter (the show took as a leisurely year to write), we found noir to be a great genre for movement theater: lots of atmosphere, melodrama, action, and imagery. These fantastic elements are introduced in the piece when a Mysterious Lady obsessed with noir moves into the building. As you know, fantasy, if it is any good, is usually rooted in some very real concerns. The building became an apt location for everyone’s desire to escape the mundane, to go on adventures while fearing the unpleasant or dangerous things that lurk down dark alleys. We found that the safe haven of each person’s apartment set up a metaphoric world balanced between the freedom and joy found “on the roof” and the danger and despair found “in the basement”. In Motion Sickness, we examined the nausea brought on by stasis and the need to get away from it all. In Apt. 4D, we look at how people survive who choose to stay put. Underneath it all, I think the show is about finding friendship and empathy where you least expect it.

As the writing progressed, we learned more about each character, and found ways to insert mini-poetic “flashes” of scenes that give you their back story. Eventually these two worlds collide, the everyday world of the Franklin Arms and the noir fantasies of the Mystery Woman. A blackout in the city brings everyone together for a final moment of resolution. Apt. 4D is also a response to the growing sense of alienation and isolation we see around us everyday. Its very easy to get completely absorbed in your own life, a narrative with you at the center and very little ability to see the world from someone else’s point of view. Often, work or a job defines us, but we purposely chose characters who are at a crossroads, either unemployed, recently moved, or unable to define themselves by what they do for a living. Yet we all still yearn for and hope we can connect to each other on a deeper level somehow (thank goodness, that’s what gives us theater people hope for the future! It is what our medium does best. And I am so fortunate to have a dedicated group of artists who like to get together in person and make work from scratch!)

Arts Fuse: How does this script fit into the often seriously zany approach of Beau Jest? It is much more direct than earlier extravaganzas such as Krazy Kat and Camino Real.

Robinson: We juxtapose the quotidian humor Beau Jest has always been know for against the darker elements the Mysterious Stranger brings into our apartment building. The little human moments of recognition, the daily struggles we all experience just trying to get through the day (in the hallways, laundry room, mail room, and the convenience store) are sprinkled throughout the show The more extravagant events happen in the basement, in our flights of movement fancy, and up on the roof. The zaniness is there, as well as singing and gestures left intentionally ambiguous. And the dark noir elements tend to become less threatening and more absurd as the play goes on and you realize no one is actually getting hurt.

Stylistically, we rotate as a company between intimate original shows and larger, more spectacle-based adaptations. About half of our plays fall into one category and half into the other. This show is in the poetic/comic/movement tradition of shows like Motion Sickness, The Cardiff Giant, and The Last Resort. Often these smaller chamber pieces help to fund the bigger more theatrical spectacles like Camino Real, Samurai 7.0, and Krazy Kat. My guess is after working this show for a couple of years, we and our larger family of designers, composers, co-directors, and actors will be itching to do something with more spectacular design elements, puppets, masks, and original music once again. Libby Marcus, who often designs and directs for us, is busy now with a two-year project building and staging two Beckett short plays, Act Without Words I and Come And Go, using marionettes. I am going to be a technical assistant on that project next year, so our next “big” Beau Jest show will probably be 2016.

Arts Fuse: A powerful sense of paranoia and violence runs underneath a seemingly bland surface in Apt. 4D. Are you saying that we should distrust fantasy?

Robinson: Not at all, we love fantasy. That’s why we make theater pieces, it gives us a chance to escape the ordinary for a few hours and do something wild, unbridled, and touching upon the infinite. But fantasy needs to be rooted in something very real if it is to be of any human concern. But there is something essentially dark, lurid, and “cheap” about the film noir world and staged violence, and we wanted to frame it in a way so that it would have resonance in the real, human, natural world that the characters live in in the play. We needed to let the audience know what kind of a ride they were going to be on, what kind of people we were, and where we wanted to take them, someplace human and hopefully a bit profound. Noir itself is just a vehicle for making it an interesting ride, and a metaphoric extreme for expressing some of the very real fears each character has in their own inner lives, while giving us a chance to expose some of those concerns through a lens darkly. Its also just a heck of a lot of fun to adopt campy noir swagger, dialogue, characters, and plot points whenever we needed to stir things up.

Arts Fuse: The play deals, humorously, with issues of disconnection and role playing — how much of Apt. 4D takes its inspiration from improv?

Robinson: In the early stages of writing, I put actors together in the same room and give them several weeks of open-ended improvisational exercises (some physical and some verbal) to see what they come up with. We start out by moving and thinking out loud together, doing a lot of character work and relationship development through improvisation. Eventually, certain characters and movement sequences begin to rise to the top, take shape, and dominate the narrative. We then do the much harder work of writing, organizing, and re-writing those ideas to fit a theme and turn it into a cohesive whole. In the end, the finished product is a script and a choreographed piece.

While almost every moment in the show began as an ah-ha moment explored through improvisation, it is now fully choreographed and scripted. In some instances we would take a location or a character prompt and try 5-6 solutions to the same question. If a particular scene or solution felt right, we would keep it until something better came along. If nothing worked, we threw it out and asked other questions. Eventually, we had to step back and look at the foundation, make sure everything we had was needed, and then cut anything that felt extraneous or served no purpose in the final piece. After a rough draft started to take shape, we called in people who have worked with Beau Jest before and who know us well to look at material and see where they are confused. They offer up new ideas to work on, new questions to answer, and tell us if something we are doing is either really stupid or really worth keeping. Their reactions end up shaping the piece as well. This is all part of what has now become a recognized format for making theater called Ensemble Devising. For many years, we just called it making stuff up, or doing original work, or creating physical theater. Now that there is a term for it — Devising. I’ve been working these past couple of years on a new book on the process which I hope to have published by next year.

Arts Fuse: Talk a little about the use of music and costuming in this piece — at least on the page there is not a lot of standard noir atmospherics.

Robinson: We use a lot of Henry Mancini and film noir soundtracks to underscore the noir sections, and a wide range of contemporary tunes to set the tone for the “everyday” world of the Franklin Arms, the apartment building the play takes place in. Most of the character switching is so fast there is no time for a costume change, so we do most of it with body language and voice, and dress each character in a basic look that is identifiable mostly for the main character they return to throughout the play. We use a few accessories in some places to make switches clear.

Our biggest design element is lighting. Lighting is key to creating a film noir look, so the first person we enlisted to help us on this show was Karen Perlow, our go-to lighting designer who can make the most out of any theater’s lighting equipment. We knew the noir theme was all about light/dark contrasts, shadows, venetian blinds, and slashing diagonals with extreme angles. Light and movement are the most important elements in this show for communicating where we are and what is going on.

Arts Fuse: What is the biggest challenge in staging this production? There is quite a bit of quicksilver morphing from one character into another going on.

Robinson: Being in this show is like being inside a Swiss watch. Every actor has a very precise movement pattern and dialogue scheme that intersects with the other three actors on stage to create moments of suspense, comedy, action, despair, or joy. Every gesture is choreographed, and every image on stage is calibrated with an almost musical sensibility; timing is everything. We’ve made the four main characters easy to recognize. All of the locations and peripheral characters are established through clear shifts in physicality, voice, and location on stage, along with cues from the lighting.

For me, it is a delight to perform in, and a great personal challenge to be able to make every moment count and play as intended. I work with these actors because I know them well, I like the way they move, and we all intuitively pick up on each others actions and timing in a way that works like a well-oiled machine. Because we wrote the material together, when any note or moment rings false we all know it. It becomes a visceral experience for us and the audience to share in. the biggest challenge is being able to stay present and in the moment for every beat of the show, like a Beethoven string quartette.

Arts Fuse: What is it like to celebrate the 30th year of your theater troupe? Given the mortality rate of most companies, you are an infinite jest.

Robinson: Nice pun! I’m glad we are still here 30 years later. Our first big challenge as a group came after several years of working together with the same cast. Two members of our core company, Karen Tarjan and Steve Herson, decided to move together to Chicago. We had a board meeting, and discussed whether to try to replace them or call it quits. Everyone wanted to continue, so we held auditions, and started a new era with Jay Bragan, Lauren Hallal, and Patrick Sweetman on our next original show about truth and deception, The Cardiff Giant. We then talked board member Larry Coen into getting on stage with us for our production of Krazy Kat, and entered a very productive phase that has continued to this day, using our core team of actors and designers to develop new projects, and bring in new actors and designers as needed on a show-by-show basis to supplement our core ensemble. And while our core mission of creating actor-driven work with a strong emphasis on physicality and a touch of absurd humor continues to underpin all our work, we have managed to stay fresh by exploring new sources for each show, taking a major plunge into Tennessee WIlliams’ territory for the last three shows, and continuing to research how text, gesture, and imagery intersect to make meaning on stage.

We also don’t take ourselves too seriously. We decided several years ago to keep our day jobs and only get together to make work when we felt a strong need to do something, which has allowed us as a small organization to stay afloat without having to invest in a large staff, infrastructure, or incur any debt. We raise funds for each show as it comes along, and then book that show and tour it until we decide it is time to make something new. We do it for the joy and communitas of making theater together much as we do for responding to the world around us through art. And if someday nobody wants get together to make something, we will call it quits. Or maybe do a one person show…:)

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Apt. 4D, Beau Jest Moving Theater, Charlestown Working Theater