Book Review: “Natura Morta” — A Powerful Still Life in Prose

The omniscient narrator in Natura Morta is flawlessly neutral, allowing the images, minimal action, and characters’ reactions to the events of this single day in a Roman square to tell the story.

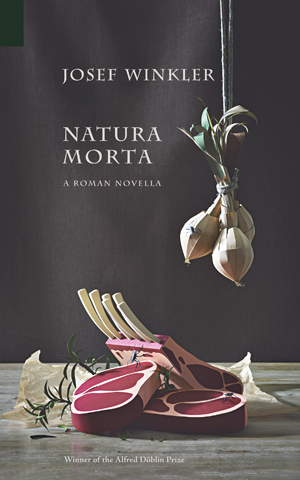

Natura Morta, by Josef Winkler. Translated from the German by Adrian West. Contra Mundum Press, 93 pages, $16.00.

By Vincent Czyz

An author with a dozen books to his credit has amassed a respectable oeuvre; Josef Winkler, one of Austria’s most renowned novelists, has an even more respectable 14 books to his name along with an astonishing 13 literary prizes, including the prestigious Ingeborg Bachmann Prize for literature, the Andre Gide Prize, the Berliner Literary Prize, the Grand Austrian State Prize, and the Georg Büchner Prize, perhaps the most important of all German literary honors. At last count his books had been translated into at least 15 languages. Mentioning Winkler’s name in America, however, is likely to draw a quizzically raised eyebrow as a response. Admittedly, before coming across his latest book, Natura Morta, rather brilliantly translated by Adrian West, I hadn’t heard of him either.

Natura Morta is not the exception in Winkler’s opus; the novella was chosen by no less an author than Gunter Grass for the 2001 Alfred Döblin Prize. There is no discernible plot, an authorial choice that, for most American readers, is akin to a scuba diver deciding to jump into the water without a mask: breathing isn’t impossible but it’s a lot more difficult. Although there are a few spoken lines here and there, a few exclamations (generally merchants hawking their wares) or the occasional muttering to the insular audience of the self, there is nothing in these pages that can be called dialogue. This shouldn’t be surprising, however, since the translation of natura morta is still life.

The original still life was a portrait of the inanimate or, more commonly, of an arrangement of mostly commonplace objects such as fruits, dead animals, wine glasses and bottles, utensils, tools, musical instruments, and vases. Religious objects (with allegorical resonance) were also common. The intent of the still life is to slow down the human eye, to make it concentrate on its surroundings. The paintings are a reminder of a world overfilled and overflowing, crowded with sights rarely accorded the attention they are due. Eventually, the category expanded to include human figures as subjects, although objects were still critical elements in the composition. Winkler’s novella shows clear affinities with the latter.

Winkler replaces the classic conflict-driven plot with a series of street scenes, described in exquisite detail, in or around Rome’s Piazza Vittorio Emanuele. His most lavish digressions are reserved for the butcher’s stalls, perhaps because they recall the literal translation of natura morta: dead nature. There isn’t a page that isn’t alive with color or texture: a piece of merchandise, a dead fish, a religious icon, a peach, or some other object or artifact. Red and black are Winkler’s favorite colors, sometimes appearing five or six times each on a given page. Nuns are virtually ubiquitous, as are gypsy girls and women—perhaps a balancing of opposites, of the sacred and the profane (even as black, possibly representing death, is balanced by red, symbolizing blood and life). Similarly, crucifixes abound—in silver, gold, or even tattooed—and these seem offset by a recent fashion trend for baby pacifiers, which dangle from key chains, earlobes, necklaces, and bracelets. While the cross is a religious symbol of mortality, the secular pacifier is associated with birth and new life. Even if the crude contrasts I’ve set up have some validity, Winkler is far too canny a writer to fix things in such simplistic terms. Instead, the book is filled with ambiguities, so that we are given to understand, for example, that life comes from death—in the butchers’ stalls, for example, where the slaughtered animals are sold to feed the city’s population. Of course, this method also resonates with traditional still life painting, in which tokens of life were often juxtaposed with memento mori, such as human skulls.

Here’s a representative sample of Winkler’s prose:

A black-veiled nun, holding plastic bags full of cucumbers, apricots, and onions in one hand and pressing two tall blond Barbie dolls wrapped in plastic to her breast with the other, stopped before the tomato vendor, whose vegetable knife hung from a lanyard around his neck, laid the dolls on a wooden crate, and asked for a few kilos of tomatoes on the vine. The clothes of an old gypsy, dressed in black & kneeling on the ground, were laid out for sale over an open black umbrella. A sixteen-year-old gypsy girl made her younger brother grimace when she pulled a pair of boxer shorts printed with red hearts from a bundle of underclothes, pressed them into his hand, and shoved him on the shoulder, making him walk from stall to stall, offering the underwear for sale.

The objects at the center of a typical still life look to be both haphazardly arranged and suggestive of a hidden order. In the same way, individual scenes in Winkler’s novella seem also seem to hint at significances beyond their artfully reconstructed surface details. The approach here is not montage, in which images flit past and tease the eye, but more as though a camera, following a character, slowly panned the scene, zooming in on a dead octopus on a scale, moving out again, and then taking up with another character. The same figures appear throughout the novella, including “A habitué of transvestites, the fat fishmonger with three day’s growth of beard, wearing a shirt printed with the word Hawaii and the image of a surfer with his hands aloft, [who] answered to the nickname Frocio” as well as two other fish-sellers; two teenaged Moroccan “rent boys,” a wizened frog peddler with “black chimpanzee’s” fingernails, and a “fig vendor who stood at the gates of the Vatican on Sundays offering fresh gifs from her garden to the tourists and pilgrims streaming by.”

The novella is not, however, a formless procession of nameless characters and visual vignettes. The ‘story’ is shaped by the movements of the fig vendor’s son, a “black-haired boy, around sixteen years old, whose long eyelashes nearly grazed his freckle-studded cheeks and who wore a silver cross around his neck.” Winkler’s subtle ordering touch is discernible (barely) at the first page, where a woman is headed to “the metro entrance in Stazione Termini,” carrying a copy of Cronaca Vera, a tasteless weekly “in which tragedies from throughout Italy—illustrated with hearses, eyewitnesses, chesty women, and Mafiosi—are reported every week.” Termini, of course, suggests end, and the presence of Cronaca Vera foreshadows the tragedy that will take place before the day is over. A good Samaritan calls out “Wishes and many beautiful things” on the opening page as well. Arguably, these (desires and things) are the twin engines driving this narrative.

With rare exceptions the sentences are beautifully balanced (much also to the credit of translator West), and as laden with visuals as a feast table in the era of the Dutch masters was loaded down with victuals. The omniscient narrator is flawlessly neutral, allowing the images, minimal action, and characters’ reactions to the events of this single day in a Roman square to tell the story. I was reminded slightly of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s dispassionate voice, but Winkler, despite complete emotional disengagement—even when narrating in gruesome detail a butcher splitting open the head of the lamb or a hare—somehow conveys more warmth than Robbe-Grillet. An apter comparison would be the understated poetry of John Berger’s narrative voice in A Painter of Our Time (a much overlooked and underrated novel).

While Natura Morta as I have described it may seem somewhat slow going, I read it in three sittings —attribute it to Winkler’s skill with language and his gift for composing scenes, both in terms of their movement and the counterbalancing imagery. With its open love of the sensuous, this slim volume lingers curiously long in the mind, staining memory a subtle hue in the way that, hours after the sun has disappeared behind the horizon, the sky still holds its glow.

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, The Georgetown Review, Tin House online, Louisiana Literature, Southern Indiana Review.

Tagged: Adrian West, German literature, Josef Winkler, Natura Morta