Book Review: “On Leave” — An Engaging Anti-War Story From France

“On Leave” is a worthwhile novel that deserves this English revival because it convincingly conveys the alienation felt by soldiers who return home on a brief leave from hostilities taking place abroad.

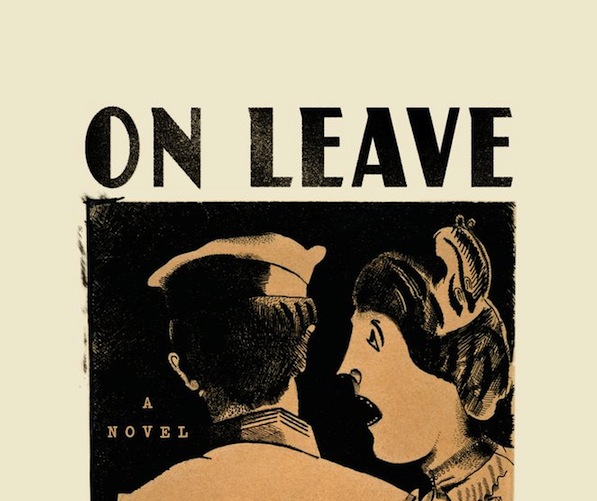

On Leave, by Daniel Anselme. Translated from the French by David Bellos, Faber and Faber, 199 pp., $24.00.

By John Taylor

David Bellos’s unexpected translation of Daniel Anselme’s long-out-of-print La Permission (1957) comes accompanied by high praise. The dust jacket calls this story set and indeed issued during the Algerian War (1954-1962) a “lost classic,” and Publishers Weekly similarly labels it a “forgotten classic.” The translator more precisely notes in his introduction that On Leave is “an important book” that “has become more precious with the passing of time. It tells in simple terms of the damage wrought by an unpopular and unwanted war on young men who are obliged to fight it.”

This is an apt summary. The equally forgotten Anselme (1927-1989), whose real name was Daniel Rabinovitch and whose other books—À l’heure dite (1948), Les Relations (1976), and Le Compagnon secret (1984)—are also out-of-print, was a communist writer and journalist who had served in the French Resistance during the Second World War.

Although On Leave is no classic, it is certainly a worthwhile novel that deserves this English revival and that convincingly conveys the alienation felt by soldiers—here French, but in fact any soldiers—who return home on a brief leave from hostilities taking place abroad. American readers will find analogies with veterans’ tales of coming back from Vietnam, Iraq, or Afghanistan. One of the rare contemporaneous accounts of the Algerian war—let’s also remember Daniel Zimmermann’s harrowing short-prose texts, Nouvelles de la zone interdite, initially titled 80 exercices en zone interdite (1961)—the book offers an engaging, oft-moving example of anti-war literature in a roundabout way.

Instead of highlighting battlefield bloodshed and backroom torture as Zimmermann does, Anselme focuses on the peregrinations in Paris, over the Christmas holidays, of three men from disparate backgrounds whom military service has turned into unlikely comrades: Lasteyrie, a corporal and incorrigible ladies man; Valette, an infantryman and electrician from a communist family living in a Paris working-class suburb nicknamed “Little USSR”; and Lachaume, a sergeant and scholarly English teacher in civilian life.

Only one scene is actually set in Algeria. And it reveals as much about the relationship between Valette and Lachaume as about the brutal routines of the war:

Attentiveness to Lachaume’s needs was one of the ways Valette expressed his respect for all the “things” his sergeant knew. But when the Algerian sun had melted them away one by one, when Lachaume had collapsed from fatigue and lapped water from a puddle in the mud like the rest of them, when he’d adverted his gaze from the villages they’d set fire to, and by closing his eyes permitted, if only very slightly, his men to turn dying guerrillas over with their boots, when he’d stopped up his ears to the wailing of women and children in the douars that the section marched through; when, at the close of day, in the acrid stench of dried sweat, he’d put his head in his hands and told Valette again and again to stop asking questions because he knew nothing about anything anymore, the soldier’s care for him still remained, as a homage for all the “things” the arrogant young teacher had known before, or perhaps it was an act he was putting on to dispel the terror they both felt at the senselessness in their own minds.

Anselme thus probes the psychology of his characters and the socio-cultural implications of their interaction with each other as a way of evoking the treachery and uselessness of the colonial conflict. “People do not see the face of a soldier at first glance,” notes the author as Lachaume—who is the most complex character—stands on the rear platform of a bus and somewhat strangely “jut[s] out his chin as if he were giving a forceful diatribe.” “All they see is the uniform.”

Anselme, however, gives a face and a personality to each of his characters, who are portrayed as individuals caught up in a nightmarish fatality and impotent in the face of it. Despite their efforts to find solace in alcohol, gambling, and sex, they are unable to enjoy this brief respite from the conflict.

Despite their good will, friends and family cannot fathom what the men have experienced. During a holiday dinner at the Valette home, to which Lachaume has been invited, a local communist party official named Luc Giraud, who organizes political protest action against the French government because of the war, understands their plight no more deeply. All he manages to ask Valette and Lachaume is whether they get enough to eat in the army. The question provokes this reaction:

“Now listen to me!” Lachaume suddenly burst in, speaking loudly. “Visiting parliamentarians, journalists, parents, and friends who write to us never stop asking the same bloody question: Is the food okay? THE FOOD AT LEAST IS OKAY, AND HOW’S YOUR APPETITE?” He was screaming now. “HOW’S YOUR APPETITE?”

Nobody said anything. Lachaume shut his eyes to hide the fact that he was near to crying, and then felt Jean Valette firmly gripping his forearm.

“I’m sorry,” he said, after a long pause. “Fatigue. . . nerves. . .”

Later, during the meal, Valette similarly cries out: “What’s getting messed up over there is us! Messed up in every way! . . . We’re losing our youth, and we’ll lose the rest of our lives if it goes no much longer.” This gap between others’ discourse, however sympathetic, and the down-to-earth realities of those who are forced to fight, is often moving—or pathetic. At the end of the meal, Giraud asks Lachaume to help collect signatures for a petition.

Conversation is the essential element in the construction of the narrative—at times unduly so. The dialogues are slangy, sometimes wearisomely so; their length can make one long for descriptive passages. This is especially perceptible, retrospectively, late in the book, when the three men and the minor character Lena, a German woman who becomes involved with both Lachaume and Lasteyrie, are walking along the Seine toward the Place de la Concorde. “For the first time Lachaume realized that there were ups and downs between Saint-Michel and Concorde,” writes Anselme. “He’d learned to observe the terrain. Paris was alive beneath his feet.”

Lachaume learns to see reality anew. Stylistically, these pages are the most original in the novel. Lachaume’s powers of observation are heightened by his sense of alienation and meaningless. A more intense atmosphere is created. His existential malaise increases. It is his homeland and hometown that now form a foreign country. Details stand out: “On Quai Anatole-France, the plane trees were more numerous and formed a shimmering arch overhead. The blackened seedpods hadn’t yet fallen, and the gusting wind made them tinkle like a thousand bells.” In comparison, the table conversation at the well-meaning Valette’s holiday dinner seems interminable. From a literary viewpoint, On Leave is memorable because of the factual perceptions—the shimmering arch, the blackened seedpods—not the sociological and political concepts that sometimes encroach on the narrative.

Can this neglected novel be given a salient place in modern French literature? The postwar period was rich. Claude Simon, Marguerite Duras, Nathalie Sarraute, Julien Gracq, Samuel Beckett, Henri Michaux, Philippe Jaccottet, Yves Bonnefoy, Edmond Jabès, Louis-René des Forêts, and, to mention a few names that you may not have heard of—Charles-Albert Cingria, André Hardellet, Raymon Guérin, Henri Calet, Louis Calaferte, and Michel Fardoulis-Lagrange—all published key works during the late 1940s, the 1950s and the early-1960s. Jean Genet had mostly stopped writing, but he was there. Received notions about French literature tend to confine us to Existentialism and the so-called New Novel, but there was much more going on at the time. Ideas were in motion, and so were style and literary form.

On Leave is written in a simpler, more directly realist vein than the key French literary works of the period. It is innovative neither literarily nor philosophically, but it hauntingly explores the effects of the Algerian war on three hapless soldiers and gives a universal dimension to their suffering. For this reason alone, this pioneering engagé novel warrants attention.

John Taylor has just published a translation of José-Flore Tappy’s collected poems, Sheds (Bitter Oleander Press). His recent translations include works by Philippe Jaccottet, Jacques Dupin, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, and Louis Calaferte. He is the author of the three-volume essay collection, Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction, 2004, 2007, 2011). His most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012). In 2013, he won the Raiziss-de Palchi fellowship from the Academy of American Poets for this project to translate the work of the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero.

Tagged: Algerian War, Daniel Anselme, David Bellos, Faber and Faber, French literature, On Leave