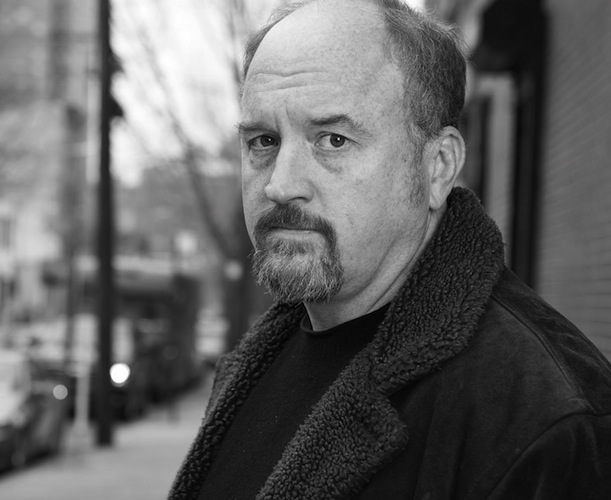

Television Review: “Louie” Redux — Better Than Ever

Louis C.K.’s “Louie” is a master class in straddling highbrow and lowbrow.

by Rob Ribera

After a lengthy hiatus of nearly two years, Louie returned for a fourth season on Monday. Louis C.K. who not only stars as his fictional self in the show, but also writes, edits, and directs, asked for the extra time off between seasons to recharge and to rethink. It was time well spent, because this new season draws on all of the hallmarks of C.K.’s talents — the show continues to push not only the boundaries of comedy, but also stretch the format of his program. Louie has never been your standard comedy offering; in the past five years we have seen Louis, as writer and director, structure episodes that contain lengthier story arcs as well as smaller vignettes. He also blends observational bits about family, raunchy discussions on sex, aging, masturbation, and good old-fashioned gross out humor. On top of that the show has made room for surreal dream sequences and forays into the fantastical while staying grounded in the realities of a father trying to raise his kids and make ends meet. In short, it is a master class in straddling highbrow and lowbrow. It is good to have him back.

Not that C.K. has gone anywhere. In the two years since Louie, Louis has been around — in a new HBO special, Oh My God, as well as brief but memorable parts in Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine and David O. Russell’s American Hustle. But he is at his best playing his alternate self — a divorced father who is helping to raise two young girls in New York City while working the comedy clubs at night. Louie struggles to teach his daughters life lessons, confront the mounting absurdities around him, stay in shape, and land a few dates. In his act he comments on all of life’s occasional triumphs and inevitable failures, combining self-loathing with bleak observations about the human condition. C.K. makes use of a freedom that earned by earlier masters of comedy — Lenny Bruce, Richard Pryor, Larry David, and others — comedians who altered the landscape of what is considered to be funny, offending many in the process. C.K. continues this admirable tradition, and he can do this without coming up against the limits his predecessors fought against.

In an interview a few years before his death, George Carlin asserted that “comedy is filled with surprise, so when I cross a line… I like to find out where the line might be and then cross it deliberately, and then make the audience happy about crossing the line with me.” This, ostensibly, is C.K.’s goal as well and, like Carlin, he also asks us to think from time to time while we laugh. Although he has not yet entered his angry elder statesman phase — a transformation that made Carlin in the late 1990s so biting, vicious, and challenging — he’s approaching that point. C.K. continues to toe the line between offending the audience and provoking them. And, as one of the best comedians working today, his popularity has given him the license to poke at taboos and ask us to join in the laughter, as he continues to surprise us.

In just the first few episodes of this season Louie admits that he’s lost track of his own age, goes on an embarrassing afternoon of gluttonous eating with his similarly overweight brother, has trouble keeping his jokes clean at a high-class charity benefit, fails at teaching his daughter a lesson about learning from her own struggles, and jokes about his willingness to use a motorized scooter (if only it were socially acceptable). All this was compelling, but the third episode of the season stands out as the one that defines the show’s possibilities. After relenting to the advances of an overweight waitress (played beautifully by Sarah Baker) at the comedy club, Louie agrees to go on a date with her. It starts out innocently enough, though it is clear that there is no chance that it will evolve romantically. An offhanded comment about how she is not overweight turns the tables, however, giving Baker the opportunity to lay into Louie about his hypocrisy. What follows is a lengthy monologue about how we see women, how women are asked to see themselves, and how much damage is done by the superficiality of it all. Here we move into different territory. After being disarmed by humor, we are hit with a dose of reality. Is it a little overwrought and earnest? Perhaps — but at least it’s taking that risk. This is a memorable sequence (one of its finest to date) on a show that will remembered for a lot of challenging moments.

When a comedian crosses lines, he or she confronts our sensibilities, which hopefully forces some self-reflection. The best of C.K.’s material points out life’s absurdities, admits that he’s a part of the inanity, and infuses the resulting farce with a sense of curiosity and morality. To wit: human beings are lazy and selfish, yet we have the capacity to do so much for others. We are afraid to die, yet we don’t take care of ourselves and each other. Picking apart these paradoxes are what make for great comedy. While the show’s occasional tastelessness may turn off some, and its earnestness come off as preachy, C.K.’s voice is helping to shape a generation of comedians to see that the power of humor can be used to start a serious conversation.

Rob Ribera is a filmmaker and music video director in Boston. He is the co-creator of the music website Sleepovershows.com, and is currently working on his Ph.D. in American Studies at Boston University.