Theater Review: “Absence” — Movingly Moving Toward the Null Point

The protagonist may necessarily be passive in the face of his or her diminishing mental condition, but art must rage against the dying of the light.

Absence by Peter M. Floyd. Directed by Megan Schy Gleeson. At the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre, Boston, through March 2.

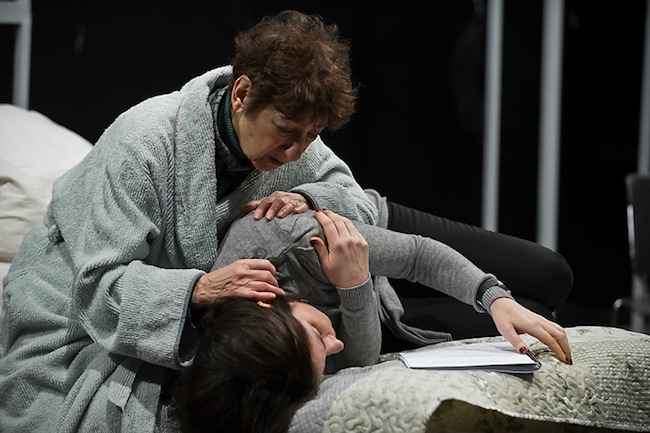

Joanna Merlin (Helen) and Bill Mootos (Dr. Bright) in the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre production of “Absence.” Photo: Kalman Zabarsky.

By Bill Marx

Absence is expertly engineered to tug on the domestic heartstrings: watching a human being slowly but surely fade away, his or her mental faculties diminishing to the point of no return, can’t help but be a moving experience. This earnest drama about Alzheimer’s disease marches through what are (alas) becoming the familiar stations of the cross: the afflicted individual initially reacts with anger and denial; growing consciousness of his or her dependence on others leads to thoughts of suicide; an acceptance of the extinction of memory and self arrives. Prepare yourself, advised Freud: All that you love will be taken from you. Including your essential sense of you. But a playwright must redeem the dying fall, transform helplessness in the face of the decay of body and mind into a dramatic experience that is audacious, poetic, and emotionally ferocious—the character may necessarily be passive in the face of his or her condition, but art must rage against the dying of the light.

Unfortunately, dramatist Peter M. Floyd, despite his involving depiction of the plight of dementia, falls short of going beyond neat and reassuring pathos, his narrative sticking to a pedestrian even keel. Absence deals with the plight of Helen, a 76-year-old woman who refuses to acknowledge she is losing her grasp on reality. We see her arguing haplessly with her husband, David, going off to live with her daughter Barb, and finally moving into an assisted living facility for her final days. (Someday, someone will produce a play that reflects the situation of the majority of American families—who do not have the resources to move their loved ones into tony accommodations.) The TV-movie-of-the-week subtext to Helen’s de-evolution is that she has been a strong-minded individual who has spent (apparently) an inordinate amount of her life brow-beating her long-suffering husband and feeling bitterly disappointed that her daughter did not become a lawyer. Aside from a nostalgic memory of her beloved father (a figure of commanding power) coming home from World War II, the character does not display much generosity or empathy, the softening of her iron-willed egotism (her ‘absence’ from others) setting up the inevitable ironic rapprochement with her daughter.

Helen’s estrangement is dramatized through reflections of how she sees the world: there are sudden jumps in time, and characters speak to her in what sounds to be gibberish. This skewing of temporal perception and language is effective, but never as powerful as it might have been because the reality of the situation is crystal clear, after the initial suspicion that David is the one suffering from dementia is laid to rest. A far more successful manipulation of space and time can be found in the overlooked 2008 film Lovely, Still, which stars Martin Landau and Ellen Burstyn. Written and directed by the then 23-year-old (!) Nicholas Fackler, the movie is an imaginative recreation of what it is like to perceive life through the eyes of a man suffering from Alzheimer’s disease—it is a compelling series of fragmenting alternative realities, puzzles popping up within puzzles.

Not much is left particularly mysterious in Absence, especially because Floyd sticks in one of my least favorite theatrical devices—the ghostly all-knowing sprite, the God stand-in figure who at first torments the suffering mortal under his or her care but finally ends up bestowing a tender blessing. Here the transcendent (psychological?) jokey spirit is called Dr. Bright (played as an impish ham by Bill Mootos) who pops up in Helen’s mind from time to time to make sure that everything is pretty well spelled out for her and the audience. A kind of therapeutic hand-rail, Dr. Bright answers Helen’s questions rather than bothering to probe deeply into her mind, which would make for more satisfying drama. He may (or may not) be responsible for convincing Helen that she should not kill herself—it is one of the most energetic scenes in the production, though the idea that The Almighty (Superego?) sits on one side of the issue is debatable.

Joanna Merlin (Helen) and Anne Gottlieb (Barb) in the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre production of “Absence.” Photo: Kalman Zabarsky.

The BPT production is straightforwardly staged by Megan Schy Gleeson and generally well-acted. Anne Gottleib as Barb and Dale Place as David work (noticeably) hard to give their thankless characters, who are often little more than punching bags for Helen’s fits and accusations, some emotional complexity. Beverly Diaz supplies adolescent liveliness as Samantha, Barb’s screen-fixated daughter. Because of laryngitis, celebrated thespian Joanna Merlin could not perform the role of Helen on the day I attended. Understudy Kippy Goldfarb played the protagonist, and the talented actress gave a detailed, modulated, and always intelligent performance—her Helen was resolutely unlikeable yet admirable in her curtly dismissive efforts to evade reality. Yet Goldfarb, for all of her skill, never provides an off-speed revelation or a surprising moment. It would be interesting to see if Merlin brings a more unconventional take to the role, daring to move beyond predictable emotional responses, scrambling up the flip-flop of denial and regret.

What would that mean? My favorite treatment of the mind drifting into retreat is Conrad Aiken’s great story “Silent Snow, Secret Snow” (alas, unread now) about a child drifting into catatonia. The title image of the snow reflects our yen for oblivion, the archetypal death wish: “Its beauty was paralyzing—beyond all words, all experience, all dream. No fairy story he had ever read could be compared with it—none had ever given him this extraordinary combination of ethereal loveliness with a something else, unnamable, which was just faintly and deliciously terrifying.” Not much chance of Absence drifting into the realm of the “faintly and deliciously terrifying” with Dr. Bright in charge.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.