Book Review: Timothy Leary and Daniel Ellsberg — Dangerous Men?

By Harvey Blume

The major problem with these treatments of Timothy Leary and Daniel Ellsberg is that they portray their main characters as if there was no possible resonance between them, as if they came from different eras.

The Harvard Psychedelic Club, by Don Lattin, HarperOne, 256 pages, $24.99.

The Harvard Psychedelic Club, by Don Lattin, HarperOne, 256 pages, $24.99.

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon

Papers, a film by Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith.

More than once in “The Harvard Psychedelic Club” we learn that Richard Nixon called Timothy Leary the “the most dangerous man in America.” The title of the Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith’s recent documentary—”The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers”—quotes Nixon to the effect that, no, it was Ellsberg who was the most dangerous man in America. Of course, if you were Richard Nixon, America overflowed with dangerous individuals to so entitle.

At least superficially, Leary and Ellsberg would seem to represent substantially different kinds of danger.

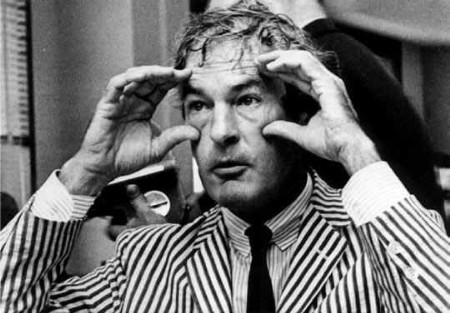

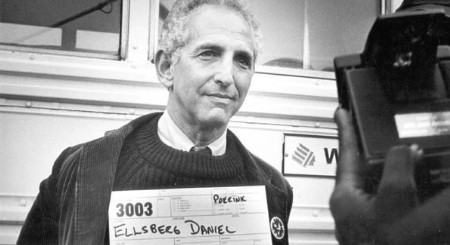

Leary was the brain changer, doing an end run around politics and psychology to tinker directly with the neural wiring he conceived of as our mental substrate—and this before the computer revolution made wiring a dominant metaphor of our day. Ellsberg was a more traditional sort of danger, a man of conscience and courage who broke ranks with the marines who had once been his comrades in arms and with his fellows at the Rand Corporation to smuggle out the 7,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers that left no doubt about the lies and cover-ups that had characterized the war in Vietnam since its inception.

Timothy Leary: Dangerous because he was the brain changer, doing an end run around politics.

That being said, just how different were Leary and Ellsberg? Though Ellsberg is not known to have taken LSD and Leary is not celebrated for anti-war activism, both drew on and fed an urge for transformation that was palpable on both the acid and anti-war end of the sixties, an urge you could feel whether you were marching or tripping.

Lattin gets at that feeling when he writes apropos the psychedelic sessions Leary conducted at Harvard that he and his cohort felt: “They were discovering a whole new world that was spiritual, ephemeral, but at the same time felt more solid, more real, than everyday reality.”

That new world didn’t need anti-war slogans to be plastered all over it; it was anti-war from its foundations on up. From the point of the new world glimpsed by Leary et al., the war in Vietnam was not just ethically misbegotten to the point of genocide but the result of a shrunken and dysfunctional worldview that would be outgrown with the help of psychedelics. (Not without some inevitable growing pains. Quoth Leary: “‘They’ll never get me up in one of those,’ says the caterpillar to the butterfly.”)

History shows that things didn’t arrive at that happy conclusion. (To follow along with Leary, lots of caterpillars said to hell with wings). But that is not to deny the utopian expectations of the day, whether you felt them on a peace march or got them from a mushroom.

Daniel Ellsberg: Dangerous because he was a man of conscience and courage who broke ranks with the marines who had once been his comrades in arms.

The problem with both the “The Harvard Psychedelic Club” and “The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers” is that they treat their main characters as if there was no possible resonance between them, as if they came from different eras entirely, eras known only nominally and for the sake of convenience as the sixties. I don’t mean to romanticize the situation: acid heads and politicos were often at loggerheads. But they at least as often cohabited, or time-shared, the same mind and body. But the book and the movie make it seem as if there was a non-negotiable cognitive gap between the Learys and the Ellsbergs.

It’s worse with the Ellsberg film. Ellsberg’s heroism—and it was nothing less than heroic for him to steal classified documents and make them public—is portrayed as sui generis. True, the risks he took were considerable and his contribution to the anti-war movement out-sized and indispensable, but others—ultimately, in their own way, millions of others—took proportionate risks and made proportionate contributions. Had that not been the case, the Pentagon Papers would have been buried, their impact nullified, and Ellsberg would not be dangerous at all.

Lattin doesn’t similarly isolate his main characters. Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (later, Ram Dass), and Andrew Weil are presented from the first as part of a self-conscious cadre at Harvard, and presented later as leaders, when not also victims to some degree of a drug culture they helped generate.

But Lattin, astonishingly, rarely so much as mentions Vietnam and never entertains the proposition that growing opposition to the war in Vietnam was nothing less than de facto set and setting for the growing use of psychedelics. It could be put the other way as well. The experience of psychedelics lent experiential underpinning to the utopian hopes for peace.

Nixon, faced with it, seemed to understand this unstable but potent synthesis better than some who look back on it.

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in the New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, American Prospect, and the Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to the Arts Fuse, and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.