Film Series Review: Columbia 101 — The Rarities, A Tasty Cinematic Smorgasbord

By Betsy Sherman

A preview of a few of the obscure gems and curios in this huzzah to Columbia Pictures.

Columbia 101: The Rarities A film series at Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, Nov. 7–Dec. 14.

I’m pretty sure the first movie studio logo I recognized was Columbia’s lady with the torch. It had a Pavlovian effect on this preschool TV watcher; her image meant I would soon be thoroughly entertained by my beloved Three Stooges.

The lady with the torch is still around, although her features have changed. Columbia, now part of Sony Pictures Entertainment, marked its 100th birthday in 2024. Celebrations at local repertory cinemas featured the studio’s Oscar winners and blockbusters. These included, during the classic Hollywood era, It Happened One Night (and a slew of other Frank Capra-directed movies), Gilda, On the Waterfront, All the King’s Men, Born Yesterday, and From Here to Eternity.

The Harvard Film Archive views the landmark from an alternative perspective. Its series Columbia 101: The Rarities both marks the 101st year of the studio and offers a course on its obscure gems and curios. HFA director Haden Guest teamed with Ehsan Khoshbakht, curator of a Columbia retrospective at the 2024 Locarno Film Festival, to program a lineup of 21 films made from 1932 to 1958. Copies of a companion book, The Lady with the Torch, will be on sale at the box office. The series covers many genres and includes short-and-punchy B-movies. Budgets tend toward the lower side. Most titles will be shown on 35mm film, and some will be screened twice. No Stooges shorts, though (whaaaah!).

One can’t talk about Columbia without mentioning Harry Cohn (1891-1958), generally agreed to be the studio era’s most ill-tempered and autocratic mogul. There’s a plethora of eye-popping stories about Cohn; many of them are collected in biographer Bob Thomas’s 1967 page-turner King Cohn.

Movie mogul Harry Cohn. Photo: Columbia Pictures

Cohn was born to Jewish parents in New York City. His tailor father was from Germany; his mother from Russia. He, like his older brother Jack, left school at 14 to help support the family. Jack got a job with Carl Laemmle, founder of Universal Pictures. Harry, a natural hustler, worked as a song plugger and maintained a lifelong passion for music. Harry joined Jack in the movie biz. In 1918, with partner Joe Brandt, they formed Cohn-Brandt-Cohn (CBC) Film Sales Corporation. Competitors nicknamed the company “corned beef and cabbage.” Dignity was regained as the partners established Columbia Pictures in 1924. Harry became the head of production on the West Coast while Jack and Joe handled the finances in New York. And so it would be for decades, as Harry found, honed, and acquired talent that would elevate the studio from Hollywood’s Poverty Row to the big time (Frank Capra was a key player in the turnaround of Columbia’s fortunes).

Harry’s cheapness was reviled by the frustrated writers and directors working for him. He had fingers in virtually all productions—although he delegated the B-movies to underlings—and craved control over his talent’s outside-the-studio lives as well. He proudly ruled by fear, profane tirades, and a willingness to sue. However, there are complementary anecdotes of his helping people.

For example, some of the figures connected with movies in Columbia 101 were generous with praise:

Mae Clarke, co-star of Three Wise Girls: “I liked Harry Cohn very much. I’ve heard a lot of other things, but I liked him.”

Director William Castle (Mysterious Intruder) about his first meeting with his mentor Cohn in the mogul’s office, which was built for maximum intimidation: “Cohn was the most dynamic, magnetic, and frightening human being I had ever seen.”

Marsha Hunt, star of None Shall Escape, speaking at a screening of the film in 2018: “Harry Cohn, whatever his social manners might have been, knew good films, and he had a kind of courage, I think, about the films he chose to make, for which he deserves great credit. Harry Cohn films very often stood for something, and not just a film. So here’s to Harry Cohn (blows a kiss). Who, by the way, I never met.”

What follows is a preview of a few of the rarities in this tasty smorgasbord of a series.

Opening night (Nov. 7) takes viewers on an enlightening journey through the ’30s, with one film made in the painful depths of the Depression during the Hoover administration and another suggesting that the reforms of Franklin Delano Roosevelt may not be enough. It makes sense to talk about this pair in the order in which they were made, but take note, Let Us Live is showing first, at 7 p.m., with Washington Merry-Go-Round at 8:45 p.m.

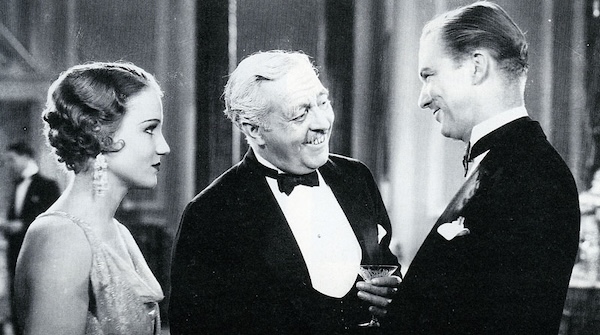

Constance Cummings, Walter Connolly & Lee Tracy (right) in Washington Merry-Go-Round (1932). Photo: HFA

Washington Merry-Go-Round was one of a handful of vinegar-tinged political movies that came out close to America’s 1932 presidential election. This eviscerating look at Congress is an ambitious, if flawed, plea for incendiary change. The film took its title from a book by columnist Drew Pearson, but was based on an original story by Maxwell Anderson, adapted by frequent Capra collaborator Jo Swerling. Walter Wanger produced and James Cruze directed.

The plot resembles that of a Columbia picture made seven years later: Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But actor Lee Tracy’s Button Gwinnett (a descendent of the Georgian of that name who was the second signer of the Declaration of Independence) is like James Stewart’s Jefferson Smith with ‘roid rage. The charismatic Tracy, known for playing wisecracking, cynical reporters, may never have played such an idealist (pertinently, Tracy’s last film role, in The Best Man, was as a former president—that film is playing at the HFA on Nov. 16 as part of a series highlighting Gore Vidal’s screenplays).

The first time Button voices his opinion in the House of Representatives, it’s akin to a virgin sacrifice: his attempt to shoot down an obvious piece of pork is met with howls of laughter. Early scenes depict the plight of the Bonus Army, the media’s term for the encampments of destitute, aggrieved World War I veterans who in 1932 demanded what the government owed them. Button uses the protesters to further his crusade to pry lawmakers out from under the thumb of a megalomaniacal bootlegger. When it hits him that he was only put in office to serve special interests, he vows that his first term will be his last: “My only constituents are the crooks who put me in office, and I’m going to use that office to double-cross them like they’ve been double-crossing the people.” Despite Tracy’s vigorous performance, Washington Merry-Go-Round is fatally ham-fisted. Whatever potency it musters is dissipated by its tendency to stop dead in its tracks so Button can make a speech. Still, its success at the box office suggests that it spoke to contemporary viewers, and it feels especially cathartic in the current moment.

In the 68-minute running time of Let Us Live (1939), the movie goes from a seemingly formulaic working-class romantic comedy to a discombobulating experience that suggests the original lady’s torch—Lady Liberty—isn’t shining so brightly. Before this wallop, however, engaged couple Brick Tennant (Henry Fonda), a cabdriver, and Mary Roberts (Maureen O’Sullivan), a waitress, find out what FDR’s New Deal alphabet soup can do for them. Brick has reserved a lot at a housing development where a sign promises “F.H.A. builds your house.” Mary lobbies for putting that off: what Brick needs first is a new taxi. Soon after he buys one, Brick and a friend are misidentified as having committed armed robbery that resulted in a murder (the getaway car was a taxi). In the courtroom, the distraught Mary tells the jury, “We’re just plain people like you are.” The verdict is guilty, the sentence is death by electrocution. The jailed Brick tries to hold onto his faith in the American justice system, hoping for a commutation. Mary searches for the real killers with the help of former police detective Ralph Bellamy.

Maureen O’Sullivan and Henry Fonda in 1939’s Let Us Live. Photo: TCM

The film was based on a 1936 story in Harper’s by Joseph Dinneen, about the true-life bungling of a case and miscarriage of justice after a murder in Lynn, Massachusetts. Once it was known that the embarrassing incident was to be the subject of a movie, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts put pressure on Columbia to cancel the film. Instead, it was demoted from an A-movie to a low-budget B. As it stands, the film seems rushed and without sufficient connective tissue. Still, director John Brahm, who left his native Germany in the ’30s, did well to employ the aesthetics of expressionism in the film’s sinister passages (his director of photography was Lucien Ballard). O’Sullivan handles her role’s demands well, while Fonda has some clumsy speeches on the way to a stunning scene showing how the once easygoing Brick has changed. That the actor went through similar plot points in Fritz Lang’s haunting You Only Live Once, and would again in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1956 The Wrong Man, makes it more of a shame that Let Us Live got the quickie treatment.

The series features two compact, chilling films made during World War II that expose Nazi atrocities and explicitly name the Jewish people as victims of persecution (several movies of the time remained vague about that point).

Address Unknown (1944) was based on the 1938 novella by Kathrine Taylor, who used the pen name Kressmann Taylor. The film adaptation (set before the war) centers on Max and Martin (respectively Jewish and gentile), their romantically entwined grown children, and how the Nazi movement rips bonds apart. The two immigrants are successful art dealers based in San Francisco; they realize it would be a boon to base Martin in Munich, to export European works for their eager customers. Max’s daughter Griselle will accompany Martin’s family because she wants to be an actress on the German stage. Her fiancé, Martin’s son Heinrich, will help run the San Francisco gallery. Martin, when back in his home country, succumbs to Nazi peans about German pride and a higher destiny, especially when the words come from the charming Baron von Friesche. As his involvement with the Reich becomes stronger, Martin worries that the letters sent to him by the Jewish Max will draw the attention of Nazi censors. William Cameron Menzies, a leading production designer, directed the film, and indeed, its proto-noir design and cinematography are responsible for much of its impact. The uniformly good cast is led by Paul Lukas as Martin. A dramatic high point is when Griselle is denounced and attacked as, during a performance, she speaks the forbidden line “Blessed are the peacemakers for they will be called the children of God.”

Marsha Hunt in the tribunal scene from 1944’s None Shall Escape. Photo: HFA

1944’s daring None Shall Escape was directed by Hungarian André de Toth, who had shot newsreels of the Nazi invasion of Poland before he fled Europe. The script, written by Lester Cole from a story by refugees Joseph Than and Alfred Neumann, imagines a United Nations having been established by the war’s end, and Nazi officials being put on trial for their crimes. In the film’s framing story, an SS leader named Wilhelm (Alexander Knox) must answer for the murder of Polish Jews. Flashback sequences, from the points of view of three witnesses, show the Polish-born Wilhelm coming back home as a wounded World War I veteran; becoming a teacher; relocating to Germany and rising to power within the Nazi movement; then returning in 1939 to carry out purges of Jews and dissenters in his hometown. Marsha Hunt plays the third witness, Wilhelm’s former fiancée, who has experienced Wilhelm’s degradation into bitterness and cruelty. Yet again, the chiaroscuro cinematography draws viewers in, this time thanks to d.p. Lee Garmes, who had worked with Josef von Sternberg.

Film scholar Annette Insdorf has called None Shall Escape part of a subset of Holocaust films that believe in “interfaith solidarity.” The script posits the trial unfolding in front of dignitaries from around the world, of many races. De Toth told an interviewer that he was present when a call came in from Columbia’s New York headquarters. Jack Cohn let loose with a vicious, slur-filled tirade about how he could never sell None Shall Escape to Southern theaters so long as it included non-whites sitting in judgment. Harry shrugged his brother off and told De Toth he could have one Black juror (himself repeating Jack’s slur). As De Toth recounted, “I said, ‘Thank you, Mr. Cohn,’ and meant it from the bottom of my heart. Contrary to the stories and jokes, Harry Cohn was a sensitive giant. I picked the blackest Afro-American, Jesse Groves, who stuck out on the jury like a sore thumb.”

Within a few years, many individuals connected to the anti-fascist None Shall Escape were deemed subversive. Knox and Hunt were blacklisted, and Lester Cole was one of the Hollywood Ten—writers who were jailed for not cooperating with the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Three Wise Girls (1932) is one of those pre-Code films in which trios of young women make mistakes and (maybe) learn lessons as they enter the worlds of work and romance. This one isn’t as wild as Warner Bros’ Three on a Match from the same year, but it has its moments. Jean Harlow, on loan from M-G-M, doffs her usual bombshell persona and winningly plays a gal with scruples, and the fortitude to hold onto them. Her Cassie, a soda jerk in a small town, figures if she’s gonna be groped by men on the job, it might as well be a high-paying job. So she goes to the big city and, with the help of her old friend Gladys (Mae Clarke), becomes a model in a couture shop. Harlow is great with a put-down, and the script gives her plenty. Marie Prevost is slyly funny as her roommate Dot, who’s decades ahead in the gig-economy trend: she types envelopes at home in order to avoid workplace groping. Gladys has a sugar daddy who’s married, and whom she moons over. Cassie keeps her mouth shut about the sugar daddy’s attempts to grope her. There’s a cryptic tuxedoed man whom Cassie dates and wonders why he hasn’t tried to grope her. Clarke’s Gladys is the weak link; her subplot drags the movie down, but impels the other two gals to seize the day.

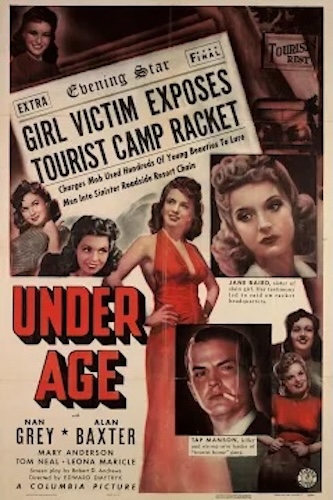

Under Age (1941) was an early assignment for director Edward Dmytryk, another member of the Hollywood Ten, who regained his career by naming names. Its novelty was putting teenage girls on the road and within the clutches of traveling salesmen. Orphaned sisters Jane and Evie Baird are released from a stretch in juvenile prison for vagrancy. They have no means of support and nowhere to go. In desperation, they take jobs that are part of a criminal scheme: a chain of roadside inn-restaurants called The House by the Side of the Road. The establishments attract male customers by employing girls who are friendly (wink-wink). Aside from the implication of prostitution, there’s blackmail, theft, and more going on. Nan Grey, as the skeptical and spunky Jane, is fairly convincing, which is more than can be said for her cast-mates. Jane, one of the sirens sent out to hitchhike and steer men towards the joint, is alarmed at how quickly the younger Evie comes to enjoy the attentions of older men who give her gifts. Jane finds the only customer with smarts and a good heart, a jeweler named Rocky (Tom Neal). Under Age trumpets its benevolence in exposing a racket, but it’s too sketchy to have more than camp value. By the way, Grey was seduced by the title character in the 1936 Dracula’s Daughter and Neal will experience much worse with a female hitchhiker in the 1945 Detour.

Under Age plays in a double-feature with Girls Under 21 (1940). Further titles with women topping the cast include Women’s Prison (1955) starring Ida Lupino, Audrey Totter, and Jan Sterling; the gothic Ladies in Retirement (1941) with Lupino and Elsa Lanchester; and the buoyant comedy My Sister Eileen (1942), starring Rosalind Russell as an aspiring writer and Janet Blair as the title character (it also boasts—a Three Stooges cameo!).

William Castle learned his chops on a series of movies based on the suspense radio show The Whistler. Columbia 101 includes the Castle-directed Whistler movie Mysterious Intruder (1946). Other suspense/film noir titles are The Killer That Stalked New York (1950) starring Evelyn Keyes; The Glass Wall (1953) starring Vittorio Gassman, with a finale in the newly opened United Nations building; and Pickup (1951) directed by and starring Hugo Haas. There are two romances, Charles Vidor’s 1944 Together Again, starring the glamorous Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne, and Nicholas Grinde’s Vanity Street (1932) with the unglamorous Charles Bickford; Nicholas Ray’s war movie Bitter Victory (1958), with Richard Burton, and Robert Rossen’s bullfighting drama The Brave Bulls (1951), starring Mel Ferrer and Anthony Quinn.

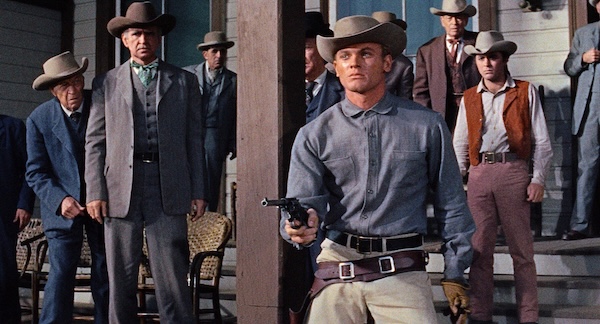

Tab Hunter in a scene from 1958’s Gunman’s Walk. Photo: Sony Pictures

Talk about rarities, it’s a treat to see a Western on the big screen. The series includes John Sturges’s The Walking Hills (1949), with Randolph Scott, Ella Raines, and singer Josh White; and Phil Karlson’s Thunderhoof (1948) and the newly digitally restored Gunman’s Walk (1958), starring Tab Hunter and Van Heflin. Karlson, best known for his noir masterpieces, had this reminiscence of Columbia’s kingpin:

“I grew up at Columbia and I worked with Harry Cohn. There was no tougher man in the whole world, and I had the pleasure of seeing this man sit in a projection room, with [producer] Freddie Kohlmar and myself, crying at Gunman’s Walk. Harry Cohn crying! He was so moved by that picture because he had two sons and this was a story about a father and two sons. He identified completely with that motion picture and he said to me, ‘You’re going to be the biggest director in this business and I’m going to make sure you are.’ Wouldn’t you know, that’s the last picture he was ever associated with. He went to Phoenix, Arizona, and died.”

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.